|

J. Elliott Casal

|

|

Joseph J. Lee

|

University students are asked to act within and master a

diverse range of genres as student writers and researchers (Nesi

& Gardner, 2012). Although the difficulty in performing such a

task is considerable for first language (L1) writers, second language

(L2) writers face similar yet also different rhetorical and linguistic

demands and challenges. As more L2 students attend U.S. universities and

colleges, the need to assist such students become successful increases.

In order to receive assistance with various writing assignments, L2

students often turn to the writing center. Intended to help such

learners develop writing abilities, writing tutors provide invaluable

one-on-one tutoring that is personalized and responsive to students’

individual needs (Reynolds, 2009).

Many L2 students at our institution, however, find it difficult

to attend physical centers due to personal, professional, or other

obligations. Additionally, the number of off-campus students enrolled in

online courses has increased in our context, and some L2 students

attend regional campuses that may lack the resources for providing

assistance to meet the rhetorical and linguistic needs of L2 writers. In

response to these challenges, the English Language Improvement Program

(ELIP) Writing Center at Ohio University developed an online tutoring

program to afford opportunities for L2 student writers in our context,

who are unable to attend our physical center, to also receive

individualized writing assistance. In this article, we describe the

development and implementation of our synchronous online writing center,

and we discuss the benefits and challenges encountered in implementing

such a virtual tutoring service.

ELIP Writing Center

Some background on the ELIP Writing Center is useful in

understanding our context. Our center is part of ELIP in the Department

of Linguistics. ELIP, an academic-literacies-for-specific-purposes

program, provides advanced writing, oral communication, and critical

reading instruction for matriculated international and domestic graduate

and undergraduate students. Although the university provides a writing

center at the library for all enrolled students, the ELIP Writing Center

is separate and specializes in offering targeted aid specifically for

L2 students. Our center’s primary mission is to support students

enrolled in ELIP courses, although we also serve any Ohio University

student in need of our assistance, even occasionally receiving writers

whose L1 is English.

Our writing center opened in Fall 2011, and we have served on

average 125–150 undergraduate and 30–40 graduate students each semester,

though the number of students attending our center has been steadily

increasing. Although our tutors are trained primarily to work with L2

students, they do on rare occasions also help L1 writers. Since our

inception, our tutors have mainly assisted L2 writers in our physical

center. However, with the challenges we encountered offering only

face-to-face (f2f) tutoring, we were compelled to explore alternatives

to continue serving L2 writers unable to attend in person. After a

semester of needs analysis and technology trials in fall 2012, our

solution was to develop and implement a synchronous online writing

center that approximates f2f tutoring, which we have been offering to

students writers at our institution since spring 2013.

The Technology: Combining Audio, Video, and Text in Real Time

To begin exploring technology options for the online tutoring

service we sought, we examined those offered by other university-based

writing centers (e.g., Purdue Writing Lab). Similar to Neaderhiser and

Wolfe’s (2009) survey, we discovered that the most common online

consultation model in use was asynchronous email-based tutoring. However

common, Neaderhiser and Wolfe find tutoring interactions via email to

be short-lived, as students often simply attach their essays and tutors

make comments in isolation before returning feedback through email. This

type of interaction more closely resembles question-and-answer sessions

than dialogic conferencing. Asynchronous options may be valuable

supplements to traditional writing center services, but the limited

interaction due to temporal remoteness is a stifling disadvantage if

they are to approximate f2f tutoring.

With this limitation in mind, we shifted our focus toward

synchronous audio-video-textual conferencing (AVT) media that allows

spatially remote negotiation in real time, bringing the dialogic and

collaborative nature of f2f meetings into the digital domain (Yergeau,

Wozniak, & Vandenberg, 2009). We identified several potential

services (e.g., Skype, Adobe Connect, Google Hangouts); however, we

discovered that most are severely limited in their treatment of

documents. Though many permit users to view a document simultaneously,

they grant editing privileges only to a single party; that is, only one

participant is free to interact directly with the text. The interaction

that these screen-sharing models offer is more akin to a

through-the-glass bank teller transaction than social activity focused

on a text.

With a clearer idea of the features we desired, we experimented

with and ultimately chose Google Hangouts (a video-chat service

developed by Google). Crucially, it encourages interactions that are

simultaneous, dialogic, and collaborative. Users have access to

documents stored in Google’s cloud-based storage system, Google Drive,

which boasts simultaneous document editing for all users. As in f2f

tutoring, the papers, voices, and individuals are at the center of

Google Hangouts tutoring sessions, not the computer screen. An added

benefit is that the software is entirely free, which permits users to

create dummy accounts to avoid sharing personal information. These

features aligned with our goals and are considered essential for

effective synchronous AVT tutorials (Yergeau et al., 2009).

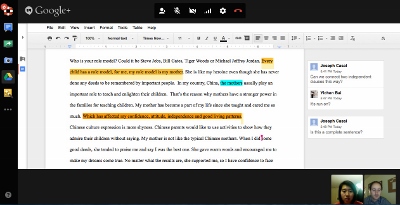

The Google Hangouts interface, as seen in Figure 1, is clean

and clear, with the document occupying the majority of screen space.

Tutor and tutee see the same interface, markings, and highlights, and

these elements are instantly updated across users; even blinking cursor

positions (within a text) are marked. However, users do not necessarily

see the same sections of a document simultaneously. This means the tutor

and tutee must communicate to ensure they are viewing the same passage

of a text.

Figure 1. Example of tutoring session in Google Hangout (click to enlarge)

As also seen in Figure 1, comments can be inserted, similar to

other word-processing software with which many users are familiar. These

comments are often used to facilitate communication because some L2

speakers prefer to see questions, new words, or suggestions in writing.

Additionally, most menus and bars can be expanded or reduced according

to preference, and participants’ faces move in real time.

The Online Tutoring Session

In AVT tutoring sessions, the interaction proceeds similarly to

our f2f tutorials. Ideally, writers submit documents in advance, which

allow tutors to prepare before meetings. For longer papers (e.g.,

dissertations), writers are asked to submit the documents in advance and

to designate the sections they wish to work on. Due to scheduling

pressures, however, most student writers do not send documents in

advance. This being the case, sessions often begin with writers

explaining their work and session goals, and tutors reading necessary

sections. Once prepared, our tutors encourage the writers to direct the

sessions according to their difficulties, concerns, and needs. In

meetings involving shorter texts or L2 writers who may be unaware of

their needs, tutors identify issues that require attention and begin a

series of questions. Regardless, real-time feedback is provided through a

combination of oral dialogues, Internet resources, and examples or

explanations inserted as comments or entered directly in the text.

As participants interact, sections are often highlighted or

colored to direct attention and facilitate understanding in the absence

of fingers and pencil strokes. As shown in Figure 1, both parties use

highlighting and comment features while discussing the writer’s

intentions and understanding. These markings may be removed by either

user when no longer necessary.

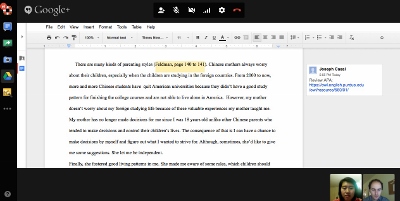

Because the Internet is available, tutors may recommend online

resources for further practice, including online citation style guides

(e.g., the one offered by Purdue OWL) or corpus tools (e.g.,

Contemporary Corpus of American English). In this way, writers may be

provided with embedded links to tools that can aid them beyond the scope

of their current paper and session. These are mostly used when writers

have needs which cannot be addressed in the allotted time but seem

capable of revising individually, if given support, at a later time. In

Figure 2, for example, an APA reference site has been recommended that

shows how to appropriately cite sources in a text.

Figure 2. Example of tutor directing L2 writer to online resource (click to enlarge)

When the writer is ready to revise the document, the tutor can

follow the reformulations and restructuring and offer live feedback. As

Google saves documents automatically and stores version and comment

history, it is not necessary to reapply changes in isolation at a later

date; the writer can revert to previous versions or revisit past

comments at any time. Although the tool set may be distinct from f2f

sessions, our online tutoring sessions offer personalized feedback and

text-centric dialogue based on similar principles.

Leveling the Playing Field

One of the most exciting features of AVT tutorial, and the

primary drive for our extension into digital space, is the ability to

provide all students with equal access to our tutoring services. As

online courses become more prevalent in many educational contexts,

including our own, a greater number of students are not physically on

main campuses where such tutoring services are offered. Through our

online writing center, we have been able to aid numerous students unable

to attend f2f sessions during our regular hours for personal,

logistical, or professional reasons. One PhD student in

interdisciplinary arts, for example, often prefers to work on her

dissertation from home, calling in during scheduled times for feedback

and discussion. Another student, who is unable to leave his children

unattended, conducts evening sessions online while they are asleep. When

necessary, though infrequent, some students have been aided online

outside of normal operating hours. Such assistance would be impossible

without the online writing center we have established, which permits

students access to tutors remotely without compromising the f2f

experience. In this way, offering AVT tutorial furthers our mission as

educators to provide students with equitable access to educational

services, thus somewhat leveling the playing field.

Benefits and Challenges of Online Tutoring

As praise of technology is often idealized, it is important to

consider the experiences of those actually involved in online tutoring.

In our case, we conducted interviews with two L2 student writers and two

tutors who were most actively involved in the online sessions. Because

our online tutoring closely approximates f2f meetings, the interviews

mostly focused on comparisons between the two approaches, and each

individual was interviewed once for about 30 minutes. During the

interviews, the student writers and tutors were asked to comment on

their expectations prior to beginning online tutoring sessions and the

convenience, comfort level, specific difficulties and challenges, and

benefits of AVT sessions. Given the small size of our interview pool, it

is important to note that these perceptions should not be taken as

conclusive.

Beyond accessibility, most themes emerging from our interviews

suggest benefits of synchronous online tutoring not present in

traditional f2f sessions, though only one of the tutees expressed a

clear preference for this medium. Both student writers reported that

they felt more comfortable during online interactions than f2f sessions.

One student indicated that “communicating from home” was more relaxed

and familiar, and therefore preferable to sessions at our physical

center. Although the other student agreed that the session itself was

comfortable, he also emphasized that travel and wait time was

drastically reduced.

Moreover, all interviewees highlighted the productivity of

online sessions. According to both writers interviewed, many peripheral

distractions occur in an f2f setting, such as people entering the room

or other interactions taking place. In online sessions, however, fewer

distractions “definitely” exist, as one writer reported. The other

student writer explained that online sessions are “even more productive”

than f2f meetings for this reason. It seems that participants in AVT

tutorials are less likely to stray from the document and more likely to

stay focused. For this reason, such tutorials may present productivity

benefits as well.

Online tutorial, however, at least through Google Hangouts,

presents a few challenges. Formatting and Internet reliability are the

most significant and recurring. Although documents composed in Google’s

word processor (Google Docs) may be seamlessly edited and uploaded,

documents stored in other formats (e.g., MS Word) cannot be edited in

the software and must be converted to Google Docs. This is not a major

difficulty, but it is an additional “hassle,” according to the tutors.

Even though this becomes easier with time, such difficulties do not

occur with printed papers. Furthermore, a high-bandwidth Internet

connection is required for video streaming. This requirement may not

pose an obstacle on many university campuses. However, because online

tutoring is aimed at off-campus students, the reliability and

performance of Internet connection is a real and relevant concern.

Additional technical concerns, such as hardware and software

maintenance, may place uncertainties on administrators, tutors, and

writers as well.

In terms of interaction, online communication may reduce the

nonverbal presence of a speaker and change the focus of a session.

Nonverbal cues, which facilitate communication with lower proficiency

writers, are more difficult to recognize. While most tutorials occur

through live video interactions, video is relegated to a tiny box in

favor of a larger document viewing area. In turn, micro-facial

expressions and subtle body language may become difficult to interpret.

Although one writer described the interaction as “fluid,” the other

writer noted the lack of “spontaneity,” referring to unpredictable

aspects of interaction such as humor. This could potentially place a

greater distance between participants. Although these difficulties may

be overcome, they require special awareness and consideration from

tutors.

Though not covered in interviews, it is important to note that

some writers expressed preferences in online sessions that cannot be

easily addressed in f2f sessions. One student, who feels uncomfortable

in person and on screen, chooses to conduct the online sessions without

video. The presence of real-time audio, even without video, allows for

dialogic interaction and collaboration while maintaining low anxiety.

Another student, concerned with a lack of oral English proficiency,

elected to listen to real-time audio and respond only through text and

highlighting.

Conclusion

As online courses become more prevalent and more learners study

remotely, the question of how writing centers can equitably offer

services to L2 students may become more pressing. To offer these

students tutoring experiences that approximate f2f sessions that their

peers have access to, we have established an online tutoring program

using Google Hangouts, an AVT tool that encourages real-time

interaction, dialogue, and collaboration. Although we have offered this

form of tutoring for only a little over a year, we have found the

interactive and collaborative experience participants encounter in this

digital space potentially as effective as the one experienced in our

physical center. Perhaps no existing virtual media can truly overcome

spatial remoteness, but the synchronous online tutorial we offer seems

promising because it approximates f2f tutoring and provides equitable

access to those L2 students needing writing assistance from a distance.

References

Neaderhiser, S., & Wolfe, J. (2009). Between

technological endorsement and resistance: The state of online writing

centers. Writing Center Journal, 29(1),

49–77.

Nesi, H., & Gardner, S. (2012). Genres across

the disciplines: Student writing in higher education.

Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Reynolds, D. (2009). One on one with second language

writers: A guide for writing tutors, teachers, and

consultants. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan

Press.

Yergeau, M., Wozniak, K., & Vandenberg, P. (2009).

Expanding the space of f2f: Writing centers and audio-visual-textual

conferencing. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and

Pedagogy, 13(1). Retrieved from http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/13.1/topoi/yergeau-et-al

J. Elliott Casal is currently a graduate student in

the Department of Linguistics at Ohio University and the assistant

coordinator of the English Language Improvement Program Writing Center.

His research interests include English for specific/academic purposes,

second language writing, and computer-assisted language

learning.

Joseph J. Lee is the assistant director of the English

Language Improvement Program (ELIP) in the Department of Linguistics at

Ohio University and the coordinator of the ELIP Writing Center. His

research and teaching interests are English for specific/academic

purposes, genre studies, classroom discourse studies, advanced academic

literacy, and teacher education.

|