|

Visualize a recent pronunciation lesson you taught. Who is

modeling the pronunciation point being taught or practiced? If you are

like most of us English language teachers, the answer is “Well, me of course.”

Many TESL instructors believe in the value of learner-centered

communicative tasks to promote language acquisition. And many also

believe in the power of learner autonomy and choice to promote

motivation and learning beyond the classroom.

But in pronunciation instruction, these same instructors also

tend to believe in the effectiveness of explicit focus on form (i.e.,

the specific forms of English sounds and sound patterns), including

clear modeling and feedback in pronunciation teaching. This modeling is

often done by the instructors themselves and/or is provided through

recordings of other English speakers to give students access to

variation in accent, gender, and so on.

Are these beliefs incompatible? Do we need to revert to a

largely teacher-centered classroom to effectively model and lead

pronunciation instruction and practice? Can we imagine a pronunciation

lesson in which students are modeling pronunciation points to each

other? Or is it only effective to put learners in charge when activities

are communicative and less controlled?

This article provides some ideas for how to put students in

charge of guided pronunciation practice in various peer-teaching

classroom activity formats. Many of the drills and activities that we

use to introduce, intensively practice, or review pronunciation points

can be adapted to a peer-teaching format with the help of the following

steps and criteria. Examples that conform to these guidelines

follow.

Steps for Pronunciation Peer-Teaching

When reflecting on how to make a pronunciation lesson more

student-centered, consider if you can do the following:

1. Identify a set of pronunciation features that can be divided

into different items (e.g., a set of different phonemes, a set of

different stress patterns, a set of different patterns of question

intonation). If students in your class have the same first language,

focus on target features that tend to be somewhat or very difficult; if

your class includes a mix of first languages, include features that tend

to be difficult for each of the first language groups. In other words,

don't include items that are already easy for everyone in the

class.

2. Give, or have students choose, features from this set that

they feel most confident modeling for others. Note that these features

should be something that students (a) are already able to produce well

or (b) are able to gain control over autonomously through their own

resources (such as online resources or dictionaries), so that with

practice they are able to perceive and produce well enough to model and

give feedback to others.

3. Set up activities that allow individuals, pairs, or groups to teach each other what they know.

Criteria

While designing your activities, check them against these two criteria:

1. Do students have some control over what they choose to learn and what they choose to teach?

2. Is the lesson structured to support and encourage peer teaching?

Examples

Below are four examples of possible activities, two that focus

on segmentals, one that focuses on word-level stress, and one that

focuses on suprasegmentals. In each of these examples, the instructor

can act as a classroom resource, listening to and verifying

pronunciation, but does not lead the lesson beyond helping with

classroom management.

Example 1: Segmentals (Vowels)

Adopt a Vowel: Jigsaw and Fluency Line Formats

Ask small groups of students to “adopt a vowel,” for example,

using the color vowel chart as an anchor (e.g. Taylor &

Thompson). Each group has one

target vowel. Groups brainstorm a list of 5–10 words or phrases that

contain that vowel and practice saying the words or phrases clearly,

using online audio dictionaries to check their choices. Groups can then

re-form to form jigsaw groups (each new group contains members from the

other groups). Members of new jigsaw groups can lead practice with one

another on their example words and phrases.

Jigsaw groups can then create sentences or a short role-play

using at least two words that contain each sound. One or more groups can

show sentences or perform the role-plays to the class while the class

tries to identify which words contain the target sounds.

Reviews in later classes: Vowels can be

practiced in a fluency line. In pairs, students select and hold a

colored card with one or two example words with the target vowel on it,

and their partner needs to repeat these words, then say and write two to

three more words that have that sound before the fluency line shifts to

the next person. These words can be checked at the end in groups or as a

whole class.

Criteria check:

- Autonomy/choice: Students can select vowels they have more

confidence in or want to challenge themselves to master. Then they can

check sounds with an online dictionary.

- Peer teaching: Students are responsible for partners'

accuracy in identification or production of the vowel in example

words.

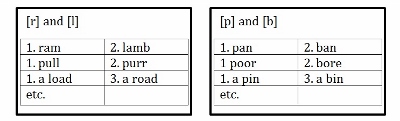

Example 2: Segmentals (e.g., consonants)

1 or 2? Minimal pair listening drills

This activity is a twist on a common pair-practice drill and is

for classes that contain two or more first language (L1) groups.

Instead of a one-size-fits-all minimal pair practice in which all

students do controlled practice on the same segmentals for the same

amounts of time, identify which sounds are troublesome for the specific

language groups in your class, and prepare materials that allow

different L1 partners to listen for sounds they find easy, but produce

sounds they find difficult.

Prepare minimal pair sheets (or have students prepare them)

that contain minimal pair contrasts that are difficult for the various

L1 groups in the class. Students choose which contrasts they want to

practice, then find a partner from another L1 who has chosen another set

of contrasts. Students take turns saying either the word from column 1

or the word from column 2, while their partner holds up one or two

fingers to show which word he or she hears. Students can switch partners

several times.

Example partial material:

Criteria check:

- Autonomy/choice: Learners can choose to practice sounds that are difficult for them.

- Peer teaching: Students can model and correct these target sounds for their partner.

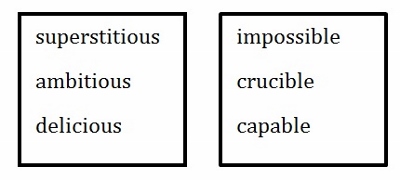

Example 3: Multisyllabic Word Stress

Show the Stress

Create cards (or have students create them) that have a few

examples of a multisyllabic stress pattern on each card, with additional

space underneath to write more. Individuals, pairs, or groups can

confirm the stress pattern with a dictionary, then brainstorm several

more examples of that pattern. Note: Students should not mark the stress on the words on their

cards!

Students then form jigsaw groups, form a fluency line, or

wander freely around the room to show each other their cards and try

reading the words they see. If the reader puts the stress on the wrong

syllable, the partner can ask for another try and/or provide hints by

humming the words and using gestures to show stress. (Note that students

can also teach each other what the words mean.)

Students can take a pretest on all the target patterns to help

them notice and focus on difficult patterns during the activity, then

can take a posttest to see their improvement.

Example cards:

Criteria check:

- Autonomy/choice: Students can randomly or purposefully choose a stress pattern they want to focus on.

- Peer teaching: Students are responsible for making sure their

partners are perceiving and producing the patterns clearly.

Example 4: Suprasegmentals

Hearing It in Action: Finding Examples in Authentic Materials

After students have had some introduction to suprasegmental

patterns such as question intonation, focus word prominence, linking, or

reductions, their homework is to find a clear example of the pattern

from the Internet, a video, a podcast, or a recording they make

themselves (e.g., a recording with a conversation partner). Students

present their examples to groups or to the class and lead classmates

through practice of transcripts of the pattern.

Criteria check:

- Autonomy/choice: Students can find their own examples.

- Peer teaching: Students present authentic material and lead peer-practice activities.

These examples are not intended as just recipes to follow

strictly, but as starting points for further adaptation in the

curriculum, as needed. As in any class involving peer teaching, it is

very important to foster a trusting classroom community where students

are responsible for and want to help each other. Embarrassment or

competitiveness should be minimized, and all members of the class should

be seen as valuable resources. The teacher can model how students can

provide correction by doing a few examples with several students first

and having students model together for the class. Another point to keep

in mind is assessment. Activities should be designed to be easy to

assess by the students themselves or easy to check later as a class in

review. Students should have accountability to themselves and each other

just as they would to a teacher.

As students become more comfortable leading pronunciation

instruction and practice, they will see that they do not need to rely

only on a teacher to improve, and in this way they will become the

autonomous learners we hope to foster.

Perhaps if any of these ideas prove to be useful to you when

you teach pronunciation, the answer to the question posed at the start

of this article may become, “Well, it depends!”

References

Taylor, K., & Thompson, S. (2013, January 1). Retrieved October

9, 2014, from http://colorvowelchart.org/

Keli Yerian is senior lecturer and director of the

Language Teaching Specialization Master of Arts degree in the Department

of Linguistics at the University of Oregon. Her interests focus on

gesture in professional communication and teacher

education. |