|

Although there are a plethora of teaching strategies that

target intrinsic motivation and higher order thinking, few are as

effective as student-led discussions. Research shows a majority of

students report feeling much more motivated to complete the task at hand

when given the opportunity to freely discuss the ideas of the class in

relation to the content being taught (Brisbin 2015). Through thematic

units in an intensive English program (IEP) as well as culturally

sustaining pedagogy courses in graduate level programs, I have

successfully organized student-led discussions and projects. This

results in enhanced confidence and motivation, leading to greatly

improved listening and speaking skills. The following are examples of

these successes.

Jiangsu Education Department of China: Teacher Training

In the summers of both 2017 and 2019, I had the opportunity to

participate in 2 weeks of teacher training (mostly EFL) throughout

Jiangsu province, China. In this program, approximately 200 teachers

come from all over Canada, Australia, and the United States. Teachers

are paired together to teach 5 hours a day, 5 days a week (30 students

per class). Teachers prepare lessons, but an advanced curriculum is also

given to the instructors by the Jiangsu Education Services for

International Exchange. The focus is on both English improvement and

teaching strategies for Chinese English teachers.

As a 1-day project, I selected two topics: the origin and

meaning of an important symbol/or item from the student’s culture and a

Chinese fairy tale/fable. Students were told that it was then their

responsibility to “educate” the class on one of these two topics. They

had to

- present the basic info in a way that engaged the class.

-

engage the class as a whole. Before presenting, they asked

the class for background knowledge, vocabulary, and so on.

-

give the class follow-up homework.

During the group presentations, the class was instructed to

take notes and add to each presentation after it concluded. For

instance, in the fairy tales, was anything missing? Could anything be

added? The next day, the groups had to go over the homework they

assigned to the class and explain how they would incorporate this into

their presentation. Finally, the class voted on one presentation that

they then perfected as an entire class, and this was presented to the

whole program at our concluding ceremony in front of administration and

local education department officials.

I found that this lent itself perfectly for use in an EFL

classroom or a classroom with little to no country diversity, because

students all share the same language/culture. The goal, however, is to

speak and present in the target language, a challenge any EFL instructor

can appreciate. An added bonus is that the foreign teacher learns more

about the local culture and language.

New York City Teaching Fellows: Teacher Training

In the summer of 2018, I taught in the New York City

Teaching Fellows program. These are graduate level courses

leading to teacher certification and a master’s degree with courses

offered at many universities. Students in this course seek an MS degree

in special education or urban education. The specific course I taught

was TAL 802: Language and Literacy (a second year course for students in

this program).

The primary texts in this course were Delpit and Kilgour

Dowdy’s (2008) The Skin That We Speak, and Paris

and Samy Alim’s (201

7) Culturally

Sustaining Pedagogies, both superb texts with strong,

engaging passages. Though I believe these texts are perfect for the

course, I wanted students to engage with them, by not only reading and

discussing them, but also by challenging their classmates to do

so.

In each session, students (pairs or groups) were responsible

for facilitating a discussion on one of the required readings for that

day. The goal was for them to help their classmates clarify the authors’

ideas, concepts, and terminology; facilitate a critical discussion; and

use this discussion to build on experience and established theories in a

way that helps inform their practice as educators. Students were put

into groups or pairs and asked to share an outline of their class

presentation with me at least 2 days in advance. Their outlines were

supposed to include the following:

- Concepts/new terminology that students may ask about

- Discussion questions and any activities/approaches they plan

to use to facilitate discussion (e.g., free writing, think-pair-share,

small group-whole class)

- Time allotted to each aspect of facilitation (not to exceed 40 minutes total)

Students were told to be prepared to facilitate for 40 minutes. The suggested timeframe was as follows:

- 5 minutes for the class to ask questions about difficult concepts/new terminology

- 15 minutes leading a class discussion

- 20 minutes engaging the class in an interactive activity

As they planned, student presenters were told to consider the following:

- What is the author arguing for or against? What does the author want us to know?

- How does the particular piece relate to the overall questions and themes of the course?

- What are the disagreements I have with the author?

- How does this relate to my life as a teacher in its many facets?:

- as a classroom policymaker

-

as a community member

-

as an activist

-

as a curriculum designer

-

as a writer/artist

-

as an observer of students’ lives and learning

- What are the implications of this reading for our schools and specific classrooms?

Students’ final assessments came from this rubric, out of a possible 15 points:

Rubric

___/2 Shared an outline with the professor at least 2 days before the scheduled

facilitation.

___/3 Provided a brief summary clarifying the author’s main ideas,

arguments, concepts, and any new terminology. You may need to engage the

class in a close reading to unpack and interrogate specific ideas

and/or passages.

___/3 Generated and actively facilitated an engaged, focused, and deep discussion of the texts.

___/4 Facilitation was dynamic and participatory. Students were actively involved.

Facilitator was provocative, responsive, and directed the discussion without dominating it.

___/3 Connected the texts to other course readings, everyday

experience, and teaching practice by providing and drawing out concrete,

specific examples from the class.

The essential components of these discussions included both

ample preparation time for student leaders and constant feedback from me

during the preparation phase. The presenters emphasized the importance

of knowledge and practice with relevant thematic terminology, dynamic

and participatory group work, and connecting the topics to other course

readings and everyday experience. Throughout these group presentations, I

noticed that student leaders pulled out concrete, specific examples

from previous classroom discussions. The class was consistently

motivated during the whole semester and we shared many stimulating

conversations related to these texts.

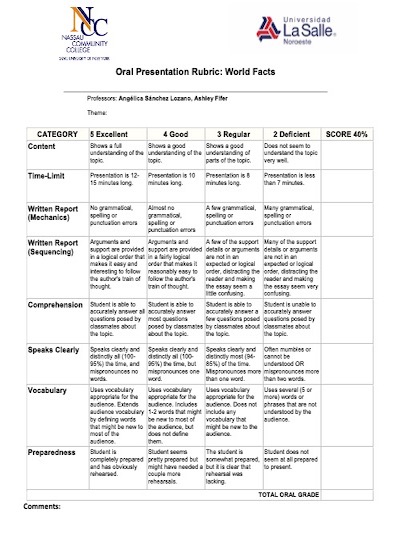

Nassau Community College: Intensive Immersion Program

I currently teach full time in an IEP at Nassau Community

College. Within this context, I participated in a Collaborative Online

International Learning (COIL) project with my advanced level class in

the fall of 2016. The students collaborated with Universidad La Salle

Noroeste in Sonora, Mexico to complete this “World Facts” project. Group

work consisted of two students each from the United States and Mexico

(four students total). The goals for this project were to increase

speaking and listening competencies in English while preparing and

delivering a project in two countries simultaneously.

In this case, my IEP students (with varying first languages)

partnered with Marketing 101 students from Universidad La Salle (all

native Spanish speakers). Students chose a topic from the Marketing 101

syllabus (geography, religion, sustainability, etc.). Students then led a

class discussion related to the topic and presented their background

information. Finally, students were required to submit a written

research paper to accompany their presentation. To complete this

presentation and final paper, students had to

- negotiate the use of Skype, Facetime, and other apps.

- communicate about and navigate within varying time zones

(Sonora, Mexico is several hours behind Eastern Standard

Time).

- brainstorm topics in a shared, common language (English).

- assign tasks to each group member.

- discuss revisions and corrections, which would be done asynchronously.

- complete a practice presentation.

- complete the final synchronous presentation, again using

various forms of technology to show their presentation.

Students were graded using a rubric the professor in Mexico and I created jointly (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Rubric for the “World Facts” project (click to enlarge).

This project was completed over several weeks in the semester

and at the conclusion of the semester, my students all scored highly on

their final listening exam. In addition, many expressed to me their

pride in the project and in their newly acquired communicative

skills.

Concluding Thoughts

Through my experiences in ESL, EFL, and teacher training, I

have found student-generated and student-led projects and discussions to

be incredibly meaningful to students and effective in increasing

listening and speaking competency.

References

Brisbin, M. (2015). Using student-led discussion strategies to

motivate, increase thinking, create ownership, and teach citizenship. Master of Education Action Research Projects. Paper

1.

http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/actionresearch/1

Delpit, L., & Kilgour Dowdy, J. (2008). The skin that we speak. The New Press.

Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (2017). Culturally

sustaining pedagogies. Teachers College Press.

Ashley Fifer holds master’s degrees in both

Spanish and TESOL from NYU. Currently, she teaches in an intensive

language program at Nassau Community College, where she has been for 14

years. She has been a regular presenter at several New York State TESOL,

Long Island ESOL, and international TESOL conferences. |