|

Zsuzsanna Kozák

|

|

Ildikó Lázár

|

“At crucial junctures,

Every individual makes decisions,

and…every decision is individual.”

- Raul

Hilberg, Holocaust scholar

Do we notice if a person living next door is

in trouble? Do we want to notice it? Do we dare to confess to ourselves that we have something

to do with our neighbor? What does it imply that in one language the

word neighbor includes its Biblical sense (a person

for whom we have moral responsibility) while in other languages we have

two separate words for those who just live close and those about whom we

are supposed to care? Also, why do we have the concept of bystander in English when in other languages it does

not have a precise equivalent? Lacking certain words is one of the many

tremendous internal and external obstacles to communication about and

with our neighbors. How can we still speak about individual choices and

social responsibility across cultures? What’s the difference between our

current neighborhood and the community in the Germany of 1938 where

people let their neighbors’ windows be shattered during “Crystal night”?

To explore possible answers, the Visual World Foundation (VWF) has been

developing an innovative international project for 3 years now, using

the exciting metaphor of The Neighbor’s Window and building on the basic

concept of an amazing United States Holocaust

Memorial Museum (USHMM) exhibition about bystanders and the

Holocaust. We hope that the description of our project will provide you

with both inspiration and concrete activities for your classroom.

The essence of the USHMM exhibition was to approach the

Holocaust from the point of view of neighbors, onlookers, and other

ordinary individuals, instead of focusing on the perpetrators and

victims, as often done by traditional studies. This

approach seemed extremely relevant to

teaching, because it is much easier to identify with ordinary

people than with heroes and villians The distance of historical times

provides a safe environment to discuss human behavior patterns,

including the mechanisms of discrimination and scapegoating, which are

also painfully relevant topics today.

VWF launched a unique project for training

bystanders to become upstanders with six partner schools in

Hungary using some seed money from the USHMM; its own resources; and

financial, professional and human support from the Embassy of Canada in

Hungary. 243 students and 17 teachers (of English,

media literacy, history, and visual arts) and psychologists worked

together to teach about human behavior in different periods of history.

We used historical photos and videos with their descriptions provided by

the USHMM to learn about history and individuals’ role in it. The

photos were incorporated in installations by the participating students

and gave a visual and textual reflection of the situations depicted in

the original images.

Selectivity: an interactive non-game”: The work of the Szombathely Secondary School of Art shows that labeling anyone will make us face ourselves in the end.

Same patterns in different places and times: The picture shows

the work of Kürt High School. There was consensus in the class: Four

patterns should be pointed out in different historical photos taken in

Germany in 1938 and in Hungary in 1943—incomprehension, pressure from

authorities, shifting responsibility, and indifference.

The uniqueness of this collaborative effort is the broad

spectrum of partner schools: from a primary school for the visually

impaired, through four different high schools (including one in the

countryside), to a university for the Reformed Church. The series of

installations created by the participating students was turned into a

mobile exhibition. It received

patronage from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and

Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in spring 2016 and since then we have

been using it as a teaching tool. The exhibition has been traveling to

different places to engage and sensitize new and sometimes not

necessarily open-minded audiences.

Students Kata Martincsák and Eszter Csordás passionately

introduce their installations to policymakers and teachers at a

conference.

Most of the student artists, peer guides, and their teachers

were present and contributed substantially to the success of the events

that accompanied the exhibition (Guensburg, 2016). For example, last

year at a conference for media literacy, teachers and representatives of

UNESCO-associated schools held at the headquarters of the Hungarian

Commissioner for Fundamental Rights, participants listened to the

students describe the creative phases of the project and their motives

in contributing to the awareness raising about the role of citizens in

times of crisis.

Miklós Réthelyi, UNESCO chair, gives a speech before presenting

The Neighbor’s Window project at a conference at the Office of the

Commissioner for Fundamental Rights

In spring 2018, the exhibition was hosted by the Israeli

Cultural Institute in Budapest. In the course of 3 months, five

workshops were organized to accompany the exhibition and help

disseminate the idea that we need to take the initiative and speak up

when human rights are not respected. Activities included simulations and

debates with follow-up reflections about the role of witnesses of

discrimination, the key role of speaking up for others’ rights, and the

great importance of participation in decision-making, including local

and national elections. Students, educators, NGO-representatives, visual

artists, journalists, and decision-makers all participated together.

That The Neighbor’s Window is a traveling exhibit with diverse

accompanying events depending on the local audiences’ needs and

interests contributes to its sustainability.

At one of the workshops, students, teachers and journalists

participated in an activity with Éva Fahidi, Holocaust survivor. Éva

suggested that we create a glossary of key terms and she cited her old

definition of a decent person: someone who always

stands up for the values of the community and never lets any of the

members be offended or attacked.

Activities for the Classroom

Here is a description of four activities from our project that

can easily be adapted to any English class with the aim of having

participants explore social issues and the nature of individual

responsibility, solidarity, and advocacy.

Péter Gács, a student from the Primary School for the Visually Impaired is examining a group of same-age Rwandan students to look for similarities between Rwandan children and his own friends.

1. Becoming aware of our own relationships with neighbors (conversation and map design)

Aims: This activity helps learners realize how little we know

about people living close by and sheds light on relationships and

alienation, as well as typical language use in such situations. Drawing

the map of communication channels helps explore the possibilities of

improving relationships with neighbors.

Procedure

-

Raise the following questions for pairs or groups to discuss:

-

Whom from your neighbors do you like the most? Why?

-

Whom from your neighbors do you like the least? Why?

-

Can you share a typical dialogue that happens between you and these two neighbors?

-

Which neighbor of yours knows the most about you? How does it feel?

-

How did s/he get all this information about you?

-

Ask participants to design a map by drawing the

communication channels in the group and also between the group members

and their neighbors.

-

Ask them to rewrite their dialogue with the disliked neighbor with I-messages showing more respect.

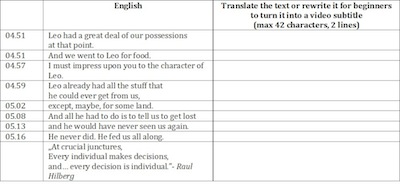

2. Better understanding and interpreting dialogues (making subtitles for a video)

Aims: This activity teaches empathy and promotes a deeper

understanding of the meaning of words and body language by practicing

respectful (accurate) interpretation and taking the spectators’ viewing

habits into consideration.

Resource: The

video introducing the USHMM exhibition serves as an excellent

medium to design dubbing and editing tasks.

Procedure

-

Ask participants to watch the video and prepare a transcript.

-

Tell them to translate the sentences, including concepts,

into their mother tongue and then shorten the text into subtitles (42

characters x 2 lines/screen max).

-

Editing the text and copying the subtitles on the video are

optional. At more advanced levels, you can screen a video in the

participants’ native language and they have to write subtitles in

English.

3. Neighbors’ participation in public humiliation (sharing associations/vocabulary with others)

Aims: This activity helps explore the visual language of

propaganda and invites learners to extend their vocabulary, communicate

with like-minded people, and tune in to a discussion about

inclusion.

Resource:

A video

from the website of the exhibition allows students to compare

their responses to others’.

Procedure

-

Screen the video.

-

Ask participants to open a new textbox by clicking on the Tags icon on the website.

-

Students enter a word to describe what they have seen in the video.

-

Then they can take a look at what words people from all over

the world entered when completing the same task.

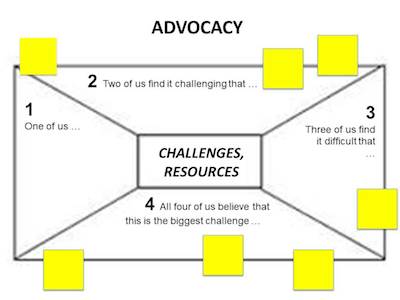

4. Advocacy (discussions and cooperative

group work, adapted from TASKs

for Democracy (Mompoint-Gaillard and Lázár, 2015)).

Aims: This activity promotes equal participation, parallel

interactions, interdependence, and individual accountability and raises

awareness of the need to take the initiative and remember our

resources.

This is the “window” pattern that participants can use to sum

up how many agree on challenges and available resources in advocacy.

Procedure

-

Put participants in groups of four and have them draw a

window on a large sheet of paper. Write the topic in the center, and

divide the window into four panels.

-

Ask participants to individually think of a group of people

they (would like to) represent in society to help them let their voice

be heard.

-

Then have them think of all the challenges they face when trying to speak up for this group.

-

Instruct them to individually write a list of these

challenges in just a few key words, and mark on their lists the two most

difficult ones.

-

Ask participants to take turns at the table to share these

most difficult challenges and count how many in their group face the

same difficulties.

-

Have participants write these challenges into the

appropriate panel in the group’s window according to how many of them at

the table share the same difficulties.

-

In the next 10 minutes, encourage groups to add resources

they could count on when trying to overcome these challenges. These are

added to the windows on yellow Post-its to make the posters visually

brighter as well as more positive and motivating.

-

Finally, pin the windows to the walls, and have the groups

present the challenges and resources in advocacy.

Conclusion

What helps us speak up for our neighbors? How can we best

represent the rights of a group of people? How can we ensure that our

voice is heard? What are the challenges we need to overcome in advocacy?

As the motto at the beginning of this article says, it depends on us

individuals what we do with the neighbor’s window. Perhaps none of us

would break it intentionally but we might not notice if our neighbor is

unwell behind that window. It may be a useful strategy to occasionally

knock on that window and start a conversation.

Developing empathy, promoting solidarity, sustaining meaningful

conversations through art, and language learning activities are the

focus of our complex educational project entitled The Neighbor’s Window.

We are grateful to Lydia Stack and Elisabeth Chan for having presented

our project at TESOL Conventions in their sessions entitled,

respectively, “Bystanders Becoming Upstanders: Media Literacy Education

for Secondary ELL Students”(2017, Seattle, Washington, USA) and

“Creative Media as Tangible Advocacy for Global Educators” (2018,

Chicago, Illinois, USA).

We are also thankful to Rosa Aronson, former TESOL executive

director, and Dudley Reynolds, former president of TESOL, for the letter

they sent to all TESOL members on 31 January 2017. Their speaking up

for international students and teachers clearly and eloquently followed

TESOL values, which gave our core team in Hungary an injection of

braveness. The public

statement they made was a great example for an upstander’s

actions that we were lucky to witness at the right moment during the

development of our experimental project in a moderately supportive

environment.

We would be delighted to receive offers to host the exhibition

and the accompanying workshops. Please contact us at neighbors@visualworld.org

if you would like more information. Photos: Judit Kocsis, VWF

References

Guensburg,

C. (2016). Holocaust lessons inspire Hungarian students’ art.Voice of

America. Retrieved from https://www.voanews.com/a/holocaust-lessons-inspire-hungarian-students-art/3298721.html

Mompoint-Gaillard, P., & Lázár, I. (Eds.) (2015). TASKs for

democracy: 60 activities to learn and assess transversal attitudes,

skills and knowledge. Pestalozzi Series 4. Strasbourg: Council of

Europe. Retrieved from https://www.coe.int/t/dg4/education/pestalozzi/Source/Documentation/Pestalozzi4_EN.pdf

Zsuzsanna Kozák is a media literacy education

advisor and a documentary filmmaker—with this background, a passionate

TESOLer. She is the founder and executive director of a Budapest-based

NGO, Visual Word Foundation, which produced several educational

documentaries for teachers of English and peace educators starring

former TESOL presidents (e.g., Philotimo

and Teaching

Tolerance Through

English).

Ildikó Lázár is a

senior lecturer at Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary, offering courses

on English language teaching methodology, cultural studies, and

intercultural communication. She has also worked as a researcher,

materials writer, and facilitator in many Council of Europe projects.

She has been coordinating a voluntary community of practice for

teachers’ continuous professional development for happy schools in

Budapest for 5 years. |