|

Thought is the blossom, language the bud; action the fruit behind it.

–Ralph Waldo Emerson

As an English Language Fellow (ELF), I was sent to Madagascar

to assist in the development of a nationwide English language

curriculum. Like most ELFs, I was sent to a country that is developing,

poor, and highly corrupt. The key reasons behind the ELF program is to

provide avenues for speakers of other languages, in developing

countries, to learn English. Why is this important? The guiding

principle behind the ELF initiative is that having a command of the

English language allows people (in the countries we are assigned to) to

consider and have access to a globalized perspective on diverse topics,

such as politics, society, and economics. Conversely, individuals who

only speak the language(s) used in the community have little power to

question those in control and are more easily influenced.

As described on theELF website, “Program participants serve as

representatives and cultural ambassadors of the United States and,

through a unique cultural exchange, they support the U.S. Department of

State’s public diplomacy mission abroad” (English Language Programs,

n.d.). In essence, ELF participants assist embassies by planting a seed

that complements their efforts to create societies that are more just

and fair.

Human Rights and Corruption in Madagascar

Transparency International ranks Madagascar at 152 out of 179

countries (Trading Economics, n.d.); on a scale from 0 (least corrupt)

to 100 (highest corruption), Madagascar received a score of 74

(WorldData.Info, n.d.), placing it well below the average among the most

corrupt governments.

In Madagascar, many basic human rights are abused, and freedom

of speech is both covertly and actively discouraged (U.S. Department of

State, 2018). Though the constitution permits freedom

of expression, the law restricts individuals’ ability to criticize the

government publicly if such criticism is seen to endanger “public order,

national dignity, and state security” (U.S. Department of State, 2018,

p. 10). Because the constitution allows for the government to censor

news, as well as grant and deny media licenses, there is little venue

for examining Malagasy social issues by Malagasy people (U.S. Department

of State, 2018). Yet, based on my own experience of living in

Madagascar for 2 years, the effects of oppression and poverty are

evident every day and everywhere; from child abuse/neglect to human

trafficking to environmental practices that have degraded the health and

sanitation of the country. Lacking any effective democratic means to

effect change, human rights violations are an accepted fact of life.

It is beyond the scope of this article to delve into the

dynamics that have created this reality. However, understanding the

backdrop is important in why I believe that the lack of dialogue about

social issues among Malagasy people exists. There is just not a venue

for dialogue, but as I found out in my work with youth groups and with

the Access program, there is a profound awareness of the injustices that

affect their lives.

Graffiti in English Teaching

Key to social justice, giving voice to these issues is part of

the solution. In this section of the article, I share a project where my

students used graffiti as a medium of expression while learning

English. In the process of unpacking the images, students were given an

opportunity to openly define, examine, discuss, and debate social

messages. Because their goal was to explain the meaning of the graffiti

to me (I do not speak Malagasy or French), they were tasked with finding

the necessary vocabulary in English to do so. This became a

collaborative effort between students who utilized the more advanced

students’ ability in English as a resource to communicate their thoughts

to me. Malagasy was allowed during discussions. I played a role by

suggesting English words or phrases that helped them clarify their ideas

and thoughts.

During this activity, using local graffiti as an English

language teaching tool became a means of raising awareness of both

social and political issues that are immediately relevant to my

students’ lives. Graffiti provided students with a ready resource for

discussion and reflection. As well, this activity has a very high

efficacy as a language teaching tool because it naturally lends itself

to raising awareness of language ability—which is important to

developing communicative language ability and solidifying language

knowledge. Students grappled with and searched for the “right”

words/phrases that I would be able to understand. Swain states, “in

producing the target language (vocally or subvocally), learners may

notice a gap between what they want to say and what they can say,

leading them to recognize what they do not know, or know only partially”

(1995, pp. 124–125). The active engagement of students during this

activity included heuristics, interlanguage, and translation. As well,

the student-generated content formed the basis for social justice–themed

English language lesson plans.

Sharing the Messages

I now discuss the activity and the results from two groups of

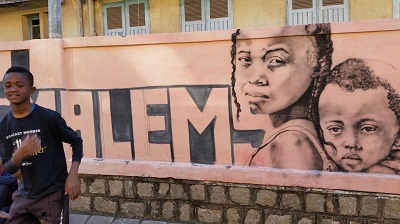

young students. The first activity used the graffiti image showed in

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Street children with the word Malem. This was painted on a wall outside an

elementary school in Antananarivo, Madagascar.

Figure 2. Youth civic center English club participants, Antanarivo, Madagascar.

The group of students in Figure 2 had mid- to high-intermediate

language ability and were between 20 and 30 years old. They regularly

attended an English club made possible by the U.S. Embassy. The activity

was simple; I asked students to name the items in the picture and then

tell me what the picture represented. The children in the graffiti are a

familiar sight in Madagascar, and one student pointed out that very

young children frequently care for their younger siblings while parents

work. What followed was a discussion about the strong family ties in

Madagascar. However, my students told me that children are also used as

beggars or forced to care for their younger siblings and/or younger

extended family members, when their parents are either dead or unable to

take care of them because of addiction problems, illnesses, and other

reasons. Of significance here is that one student noticed that this was

drawn on a wall in front of an elementary school where street children

would probably never be able to attend. Following was a discussion about

childhood rights in Madagascar in comparison to countries in the

developed world.

Using the same image, I also tried this activity with Access

students. Access participants are between 14 and 18 years old and were

chosen to participate in the Access program based on merit in school and

impoverishment at home. Their English ability varied from beginner to

low intermediate. During the identification of objects and subsequent

analysis of the image, students were encouraged to translate for each

other, and a spokesperson was chosen to present their findings to me,

allowing for the entire class to participate. The students described the

word Malem (in Figures 1 and 2) as meaning small, weak, poor, and danger. After some

negotiation, we finally settled on the word vulnerable, an adjective which very likely aptly

describes their own lives. Because of the emerging language ability, we

could not discuss the issue at length, but I felt that the process let

my students know that I, and others, understood the effects of poverty

on children in Madagascar. Sometimes, the act of defining a painful

reality is empowering, and it was my hope that they felt this.

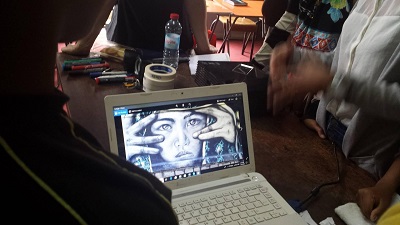

Figure 3. Students viewing “Child’s Eyes.” This was painted

on a wall just outside a very popular park in Antananarivo,

Madagascar.

In the example shown in Figure 3, students surprised me. I had

not noticed that the hands belonged to someone else, and I thought the

picture represented a child playing hide and seek! My students explained

that this child’s eyes were being pried open by an adult and forced to

see things that a child should not and does not want to see. With my

higher level English club students, this led to a discussion about human

trafficking in Madagascar and how some families willingly sell their

children as a way out of poverty.

Personally, these activities helped to raise my own awareness

of some of the social justice issues facing Madagascar and awareness

that has broadened my knowledge of the global community of which we are

all members.

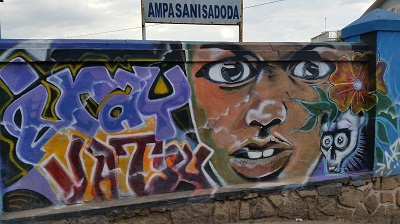

Figure 4. Detail of graffiti.

Figure 5. Saturday

afternoon Access participants. Antananarivo, Madagascar.

In the picture shown in in Figure 4, students named the items

in the picture: beautiful child, Madagascar

flower, and lemur (see Figure 5). I

suggested the word endemic and realized that a couple

of students knew this English word.

Figure 6: Zoom out of graffiti.

I then zoomed out and showed them the “big picture” and asked

them to explain to me whyiray vatsy was written next

to the art. They told me that it meant sharing food during a journey,

and indeed having travelled with Malagasy people, I have learned that

they share everything—food, accommodations, cars. After some discussion

in Malagasy, a more advanced student explained to me that Malagasy

people do, and need to, share everything with each other. I found out

later that sharing everything —through thick and thin—is a strong

cultural belief and value. Though my students could not express this to

me in English, they found the picture fascinating and it generated much

discussion in Malagasy. I wish I would have had the time to continue to

explore this topic with them.

Final Thoughts

In conclusion, the use of graffiti provided a meaningful venue

for students to begin a dialogue about social and political issues

facing Madagascar in an innocuous setting. As in any country, there is

an inherent pride of place and a need for others to see what is valuable

and beautiful—to see the big picture. Having an outsider define and

point out social and political problems is demoralizing—surely, as an

expat, I do not and cannot fully understand the dynamics of a society to

which I do not belong. In keeping with the diplomatic underpinnings of

the ELF program, my role is to allow students to express/communicate

their ideas using an English voice, not to impose my perceptions or my

voice onto them. Using graffiti and tasking students with describing it

to me, what the images conveyed to them, was an effective means to this

end.

References

English Language Programs. (n.d.). About the English Language

Fellow program. Retrieved from https://elprograms.org/about/

Swain, M. (1995). Three functions of output in second language

learning. In G. Cook & B. Seidlhofer (Eds.), Principles

and practice in applied linguistics (pp. 125–144). Oxford,

England: Oxford University Press.

Trading Economics. (n.d.). Madagascar corruption rank.

Retrieved from

https://tradingeconomics.com/madagascar/corruption-rank

U.S. Department of State. (2018). Madagascar 2018

human rights report. Retrieved from

https://mg.usembassy.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/163/2018_MDG-HRR_Report.pdf

WorldData.Info. (n.d.). Corruption in Madagascar. Retrieved

from

https://www.worlddata.info/africa/madagascar/corruption.php

Giselle

Robitaille holds an SIT World Learning TESOL master’s degree (2013).

Giselle was an English Language Fellow (2016–2018)

with the Madagascar Ministry of Education. She led a team in developing

and rolling out a new national EAL curriculum, for the public junior

and senior high secondary school levels. While in

Madagascar, she was also actively involved with the

Access program and in developing and assisting English clubs. As a TESOL

educator, her cross-cultural experiences, teaching,

and training skills have been developed in Africa, Canada, the USA, the

Middle East, and East Asia. |