|

There are multiple unknown variables with any on-location

ESOL/ESL teaching session, but it was particularly unpredictable when I

served as a volunteer chaplain with refugee families seeking asylum at a

for-profit immigrant family detention center located seventy miles from

my home during “Art Inside Karnes” (2015 and 2016). To facilitate this

art ministry amid the mixed languages, ages, and cultures of the

detained families, I fine-tuned my “signature style” layered art process

for ESOL/ESL, that I had developed for ministry and mission while I was

senior pastor at Community Fellowship Presbyterian Church, New

Braunfels, Texas.

Participants and Parameters

Most of the migrant participants were women and children who

had been victims of horrific violence, fleeing from Central America’s

“Northern Triangle” of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. The women

were trying to protect their children from exploitation and death, while

also escaping from the femicide of their homelands (Boursier 2021b).

Sporadically, there also were families from Ecuador, Nicaragua, and

Brazil. The ministry was held two to four weekdays a month for two

years. There was a staggered arrival during the scheduled time frame,

generally 9 to 11 a.m. for mixed media art and 1 to 3 p.m. for jewelry.

Overall, more than five thousand mothers and children participated

during the ministry’s two-year timeframe. Generally, from fifty to

seventy-five mothers and young children attended the regular weekday

sessions, but during the scheduled school breaks as many as 250 to 300

women and children created art simultaneously in the on-site gym. The

all-volunteer ministry occasionally received criticism from refugee

advocates for being “in collusion with the enemy” so to speak. However,

not unlike any prison ministry, the three volunteer chaplains had to

work through the authorities in order to work

directly with the women and children (Boursier,

2018).

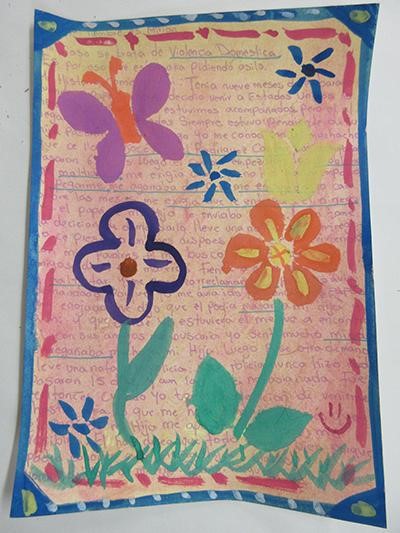

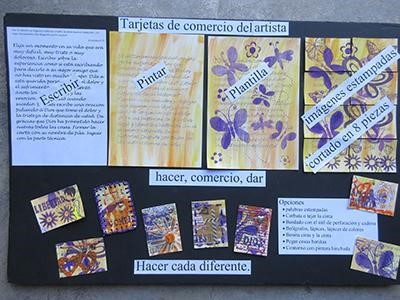

During the morning session, the participants created a mixed

media art/reflection which resembled art journaling, what art therapists

call visual journaling. Sometimes the finished product was done on

8½”-x-11” white cardstock (Figure

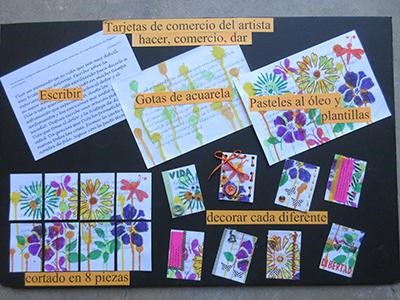

1). Other times the same paper was cut into eight Artist

Trading Cards (Figure

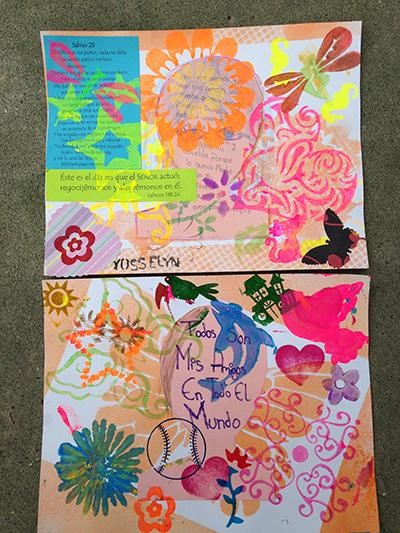

2), which the families exchanged among themselves as Tarjetas de la Amistad (Friendship Trading Cards)

(Figure

3). During the afternoon session, each person made one pair

of earrings and one beaded bracelet (Figure

4). The sessions were held in one of three small art rooms

when it was the mothers and young children. During “school vacation,” we

did art in the gymnasium with up to three hundred moms and kids. I

transported the art supplies in clearly marked transparent plastic tubs

that stacked into two oversized Pullman suitcases (Figure

5). Regardless of the location or the number who

participated, it was impossible to provide a single teaching moment to

explain the art/reflection theme and art process because the mothers and

children came and went intermittently throughout each

session.

Figure 1. “My Case for Asylum,” 14 September 2016. (Click for larger image)

Figure 2. Artist trading card, how-to example. (Click for larger image)

Figure 3. Mothers trading artist trading cards. (Click for larger image)

Figure 4. Jewelry examples. (Click for larger image)

Figure 5. Traveling art supplies. (Click for larger image)

Multilingual Art Sessions With Intentionality

The art sessions were not art for art’s sake; rather the

art/reflections were set against a backdrop of trauma theory and art

therapy practices as each guided meditation was intentionally spiritual,

pastoral, and focused on helping the women heal from past hurts while

claiming hope for a better future. I incorporated Judith Herman’s

groundbreaking trauma theory which has confirmed that the “action of

telling a story” has helped with the “transformation of memory” and

recovery from trauma (Herman, 2015, p. 183). My art/reflection procedure

also resonated with what Madeleine L’Engle (1980) wrote in Walking On Water: Reflections on Art and Faith: “In

art, either as creators or participators, we are helped to remember

some of the glorious things we have forgotten, and some of the terrible

things we are asked to endure, we who are children of God by adoption

and by grace” (p. 51). The art/reflections provided a safe place for the

mothers to voice the injustices they had experienced in their

homelands, during the journey, and upon crossing the border to the U.S.

as they began the asylum-seeking due process. The prompts helped

participants to move from their pain, frustration, uncertainty, and fear

of the present, to reframing and claiming a renewed hope for the future

that then reoriented their perspective about the present (Boursier,

2021a). My favorite projects included: preparing the mothers for the

credible fear interview, guided reflections on their personal courage,

hopes and dreams for their children, and celebrating memories from home

(Figure

6).

Figure 6. “Memories from Home” 11 March 2015. (Click for larger image)

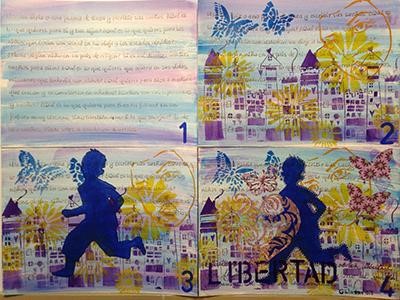

Art Inside Karnes used a directive or semi-directive approach

for the art/reflections, which offered a framework of guidance for art

participants with the written reflection and/or the art part. In

contrast, a nondirective approach means that the

art facilitator provides a blank sheet of paper and art supplies and

does not guide or prompt the participant in any way. This method is

problematic for anyone who does not know how to use the diverse art

supplies, and it also is intimidating and daunting to stare at a blank

piece of paper without having any sense of where or how to begin. The

starter prompts included with the instructions and examples were only

suggestions. Of course, the participants had the complete freedom to

reply to the questions, write about anything else they chose, or skip

the writing portion altogether and jump to the mixed media art. I used a

nondirective approach in the art sessions with children. Everyone kept

the artwork they created.

Advance Preparation Enhances Multilingual Participation

Advance prep is particularly important when facilitating any

ESOL/ESL large group of mixed ages, and different languages. It was

especially necessary for Art Inside Karnes because most of the families

were unfamiliar with the art methods, techniques, media, and processes.

To facilitate enjoyable learning, I designed the art/reflection theme

and then created step-by-step bi-or trilingual written instructions

(English, Spanish, and Portuguese) to fit a single side of 8½”-x-11”

standard paper (Figure

7). As the diversity of nationalities widened, the language

barrier became more intricate, so I also created a step-by-step visual

prototype for each layered art project so everyone had an easy way to

visually follow the various steps that went into the mixed media

collage. Initially, I made these on the size 8½”-x-11” art paper like

what the families used, and we passed these around until someone was

ready for the next art layer. It became more efficient to mount all of

the art process samples onto a single piece of black foam board because

it was easier to explain the overview for the project to a larger group.

Also, the individual pieces did not get misplaced in the piles of art

supplies (Figure

8). Art as Mission explained my art

process during Art Inside Karnes (hboursier.wordpress.com).

Blog posts included art preparation and reflection, and they also

shared insights from my ongoing learning about cross-cultural and

multilingual pedagogy for facilitating large groups of mixed language

participants who do not have any background in artmaking:

Every time I do art inside an immigrant family detention

center, I learn a bit more about cross-cultural pedagogy. Every time I

think I’ve got the process “clearly” explained it’s made obvious that NO

it is not so clear. I sneaked in a “step 2” to make it more apparent

what I’d blended together before. I also labeled each of the four steps.

The goal is to make the process easily understood [by everyone]. (Art

As Mission)

I switched blogs (refugeeartblog.com)

after Immigration Customs Enforcement rescinded my security clearance

and shut down the all-volunteer ministry December 15, 2016, but the

original blog still archives the art preparation process for Art Inside

Karnes. The new blog includes immigrant artwork and translations from

the testimonies that the mothers and children shared with me. Under the

“About” header, the new site also includes “how

to” resources to facilitate ESOL/ESL multilingual art

sessions with large groups.

Figure 7. “Hopes and Dreams” 2 November 2015. (Click for larger image)

Figure 8. Artist trading card example. (Click for larger image)

ESOL was particularly noticeable during our conversations

around the art table as volunteer chaplains did “show and tell” to

demonstrate how to use the art supplies, many which the families had no

previous experience with (i.e., watercolors, stencils, stamped shapes,

and washi tape). ESOL was evident as the multilingual group, volunteer

chaplains, detained families, and detention center staff, engaged in

small group conversations round the art tables with the mothers and

children. I often joked with the families about my mediocre Spanish as

we stumbled along together: most of the participants struggling to learn

more English, and Pastora Helena struggling to

learn more Spanish. The challenge to overcome the language barrier

leveled the playing field, so to speak, as we all sought to increase

individual and group understanding by overcoming personal fears and

inhibitions about learning a foreign language. The bi- and trilingual

printed instructions, combined with the step-by-step art visuals,

ensured that no one felt inept, shut out, or left behind due to any

language or reading limitations. Instead, these teaching tools empowered

each participant to begin where they were to learn a little bit more

English and art during each ESOL art/session

experience. Art Inside Karnes, was an inexpressible experience of

compassion, love, friendship, and multilingual/multicultural solidarity

(Figure

9).

Figure 9. Solidarity: Volunteer chaplains join hands with detained migrants. (Click for larger image)

References

Boursier, H. B. (Forthcoming 2021a). Art as witness: A

public theology of arts-based research. Lanham, MD:

Lexington Books.

———. (Forthcoming 2021b). Femicide in global perspective: An

interreligious feminist critique. In H. T. Boursier (Ed.), The

Rowman & Littlefield handbook on women’s studies in

religion (forthcoming). Lanham, MD: Rowman &

Littlefield.

———. (May 2018). The power of hope: Art inside an immigrant

family detention center. The Arts in Religious and Theological

Studies Journal. 29(2): 50-67. https://www.societyarts.org/in-the-sanctuary-the-power-of-hope.html.

Herman, J. (1992, 2015). Trauma and recovery: The

aftermath of violence from domestic abuse to political

terror. New York: Perseus Books.

L’Engle, M. (1980). Walking on water: Reflections on

art & faith. Wheaton, IL: Harold Shaw

Publishers.

All photos © Helen T. Boursier; immigrant artwork and photos shared by permission.

Helen T. Boursier isa public

theologian, educator, author, activist, ordained minister, and artist.

She has been a volunteer chaplain with refugee families seeking asylum

since 2014, including 2 years inside a for-profit immigrant family

detention center. She teaches theology and religious

studies. |