|

Trigger warning: This article

contains graphic depictions of warfare and violence.

Esta es su casa. ¡Bienvenido al infierno, compadre!

This is your home. Welcome to hell, my friend!

It was a Monday morning during fall 2018 when I was at the

school where I was conducting my fieldwork. At the teacher’s lounge,

there was so much buzz around the conversations. Everyone seemed to be

worried about what had happened over the weekend. I inquired and they told me that a friend of one of the 11th-grade students had been killed. I took this

as a shock, but for them and the community, it was business as usual.

Death is all around at these times, one of the teachers said. For me as a

researcher, this vivid image got stuck in my mind, but I was not alien

to death as I lived in a similar neighborhood in which every weekend I

would see a pile of bodies of gang teenagers at the corner of the street

where I used to live.

Since the very beginning of my arrival in Colombia, where I

conducted my ethnographic study, friends, relatives and other colleagues

always come up with phrases like “¡Bienvenido al infierno

compadre!” (“Welcome to hell, my friend!”) or questions like

“¿Qué hace en esta esquina del infierno?” (“What

are you doing on this corner of hell?”) as they feel it was weird for me

to come back home after living in North America for around 20 years.

All of this questioning kept bugging me and always came to my mind as precisely the reason I decided to come back home and conduct my doctoral study. I could have researched the North, but it would have

been detached from my roots and my social justice ideologies.

*

In winter 2019, I attended various sessions of the ethnography

lab in the Anthropology Department at the University of Toronto. One

specific workshop called my attention, “Putting the Graphic in the

Ethnographic: A Visual Ethnography Workshop Series,”as it invited me to

think about how I would visualize my experience during the fieldwork in

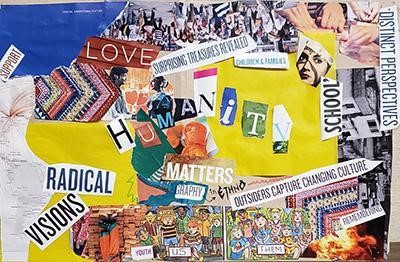

Colombia. In the collage shown in Figure 1, I depicted this experience

by using various colors, words, and cut-outs from magazines. In the

workshop, we engaged with different materials to represent our

ethnographic experiences, methods, and findings in one artistic piece. I

collected various pieces of magazines and newspapers and used glue and

markers to put them together to create Humanity (the title of my collage).

*

Figure 1. “Putting the graphic in the ethnographic.” (Click for larger image)

The collage portrays the community connections, educational

inequality, and pedagogical approach used by teachers to challenge

social injustice. For example, at the bottom of this piece of art, the

marginalized youth are represented with the word me

and the elite English-medium schools are represented with the word them with a barrier in between. In my research,

findings revealed that the teachers’ approach to teaching is geared

toward dismantling those barriers and providing the social-emotional

skills as well as the academic skills to address and attempt to mitigate

social problems in the community.

*

Hadassa, Sol, and Camello (pseudonyms) are the English teachers in this ethnography study. As Christian/Catholic, they believe that

there is much more to do than just teaching content such as grammar and

vocabulary. They believe that as rebels against the status quo, they

should use a project-based approach to address social injustice. For

example, Sol encourages her students to create projects that positively

affect their community by creating organizations to address social

issues, such as drug trafficking and unemployment. Hadassa supports her

students to visualize their life after graduation with clear objectives

about future jobs and academic careers. Camello is interested in

fostering a sense of belonging among his students by organizing projects

to project their neighborhood as a hotspot for tourists to visit so

students can practice their English skills.

This collage showcases how these teachers’ beliefs and

identities are represented and permeated in the classroom. On the top

left side, the blue color represents the Christian

concept of Heaven as salvation, “heaven as a state

in which positive feelings like joy and peace are experienced”

(Wrocławska-Warchala & Warchala, 2015, p. 251). Here, Heaven

refers to the Inside world (in the school) where

children are safe and learn. On the bottom right side, the fire represents Hell as

damnation, “hell as suffering…as lack of love and disharmony in

relationships between people…as the experiencing of negative feelings

such as fear and anger” (Wrocławska-Warchala & Warchala, 2015,

p. 254). Here, Hell refers to the Outside world (in

the streets) where violence happens, the gangs, the family violence,

unemployment, and injustice. The underlying yellow color represents the

hope and dreams for a better world, and the word Humanity represents what lies between Heaven and Hell.

*

The English lessons are geared toward reclaiming that humanity as teachers and students address social issues from a transformative lens in what I have called a Post-hum[x]nist approach to teaching. This

pedagogy centers humanity as it is connected with individuals’ lived

experiences to attempt mitigation of their violent realities. Excerpts

from the data revealed this humanistic sentiment. For example, Hadasa

says, “Quería que dejaran de ser tan terribles y trataran a

ese compañero de la mejor forma y que se esforzaran por hacerle sentir

bien a otro compañero que tiene cáncer que sus últimos días.”

(“I wanted my students to stop being so terrible and treat other

classmates the best way possible and to make an effort to make another

student, who had cancer in his last stage, feel better.”)

Also, Sol believes that if you have a good relationship with

your students, there is not much to do when it comes to learning:

“Un profesor que sea humano y que sienta la humanidad de su

grupo ya es un excelente profesor, porque ya está conectado, cuando

usted se conecta con la humanidad del otro ahí tiene ganado el 90% del

aprendizaje de los estudiantes” (“A teacher who is human and

who feels humanity in his/her group is already an excellent teacher

because she/he is already connected. When you connect with the other’s

humanity, you have won 90% of the students’ learning.”)

Borrowing from Pennycook (2018), I keep questioning what it

means to be human in a posthumanist era that promotes the individual

over the collective, or what the boundaries are between what is seen on

the inside and outside and the influence of the exterior world in our

students. With this in mind, my collage responds to that inquiry with

key phrases that captured the sentiment of my research.

- Surprising treasures revealed: The

unexpected outcomes and experiences from the research. For example, how

one of the teachers is vegan, grows her vegetables, and makes her food

from scratch every day or how I found one of the students to be a very

talented artist who makes comics for the entire school to read.

- Distinct perspectives: How the first

phase of data analysis was done with the participation of teachers and

students along with the feedback I got from colleagues and peers who

reviewed my work.

- Outsiders capture changing culture: My

outsider perspective of how the community is not a static entity but an

ever-flowing system of parents, teachers, administrators, coordinators,

and even street vendors becomes important in the educational process.

- Radical visions: Teachers’ pedagogical

approaches are geared toward making changes in and transformation of

students’ spirits and behaviours for a future change in

society.

- Love + Support: These words are

important and are at the core of the teaching philosophy. Teachers want

to make sure their activities are about caring and loving others within a

framework of a social justice and peacebuilding curriculum (SJPBC).

*

This collage experience allowed me to see the connections

between me and my research participants. Although I may have been

welcome to a place where death is all around, what I found was a

community that seeks to improve their living conditions. One of the students said, “We are not a country, we are humanity,” and that is exactly the sentiment of this research project, inviting educators and researchers to go beyond the content, to go beyond the classroom and teach for life. This collage represents not only me as a researcher but

the impact that research had in my life, because, as Wilson (2008) says,

“if research doesn’t change you as a person, then you haven’t done it

right” (p. 135).

References

Pennycook, A. (2018). Posthumanist applied linguistics. Taylor & Francis.

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood.

Wrocławska-Warchala, E., & Warchala, M. (2015). The

heavens and hells we believe in. Archive for the Psychology of

Religion, 37(3), 240–266. https://doi.org/10.1163/15736121-12341308

Yecid Ortega is a PhD candidate in

language and literacies education and the specialization program in

comparative international and development education. His general

research interests are within decolonial critical ethnographic

approaches to research in international contexts. Yecid explores how

globalization, capitalism, and neoliberalism influence language-policy

decision-making processes and their effects on classroom practices and

students’ lived experiences. His website is www.andjustice4all.ca. |