|

NOTE: This article has not been copyedited due to its length.

A persistent achievement gap between emergent bilingual

learners (BLs) and native English speakers in U.S. schools

impels teacher educators who seek to improve learning opportunities for

BLs to study their efforts. The situation is especially dire in urban

areas of Massachusetts where drop rates and reclassification of BLs with

special needs have increased dramatically since bilingual education was

replaced with sheltered English instruction (SEI) through a voter

referendum in 2002 (Uriarte & Tung, 2009). As of 2013, the state

education department mandated all teachers complete an SEI course to

prepare them to work with emergent BLs. However, research on the

effectiveness of this preparation is urgently needed. Accordingly, this

self study, a form of practitioner inquiry that takes place in a higher

education setting (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009, see Madigan

Peercy and Sharkey, this newsletter) focused on the following questions:

What difference can one course make? To what extent did an SEI course

taught within teacher education programs at a graduate school of

education prepare linguistically responsive teachers (LRTs).

Lucas and Villegas (2011) outlined orientations, knowledge and

skills of LRTs: that is, specialized language-based

expertise needed to teach emergent BLs. In brief, LRTs must recognize

how their own and students’ language and culture influence teaching and

learning; build on BLs’ backgrounds and proficiencies (DeJong &

Harper, 2005; Lucas & Villegas, 2011); scaffold instruction

(Gibbons, 2015; Walqui, 2006); and integrate language and content

instruction (Echevarría, Vogt & Short, 2013; Zwiers, 2014).

However, most U.S. teachers are monolingual English speakers

with limited second language experience (Cochran-Smith &

Zeichner, 2005); Language must become visible to teachers (Harper

& De Jong, 2004) before they can teach language demands of

classroom tasks and texts (de Jong & Harper, 2005; Santos,

Darling-Hammond & Cheuk, 2012). A primary goal of the SEI course

is to enable mainstream teachers to “see” language and explicitly teach

it. Therefore, in the course we model how language instruction can be

featured in lessons through language objectives, which focus on how

students use language to access, engage in, and demonstrate content

learning (Schall-Leckrone & McQuillan, 2014). Kinsella (2011)

provided a useful template to create language objectives with two

components: language functions and language features: for instance,

“Students will describe characters in a novel using precise adjectives. WIDA Standards (2007; 2012)

provide numerous examples of language functions within content lessons

according to English proficiency levels. Language features are discrete

language parts: phonemes, morphemes, grammar, syntax, and pragmatics

that provide students (and teachers) with a meta-language to describe

how words and word groups are formed and ordered. Academic language

functions and features must be taught, so language is no longer the

hidden curriculum preventing academic achievement (Schleppegrell, 2004;

Zwiers, 2014).

Research design

A social justice vision guided this self study— conducted

within my practice as a teacher educator at a private university in the

northeastern United States—as I believe BLs should have the opportunity

to develop language skills that equip them for school success,

professional employment, and civic engagement. Consistent with

practitioner inquiry, study participants were “regarded as knowers,

learners, and researchers,” so both practitioners’ and participants’

views of these research questions were examined (Cochran-Smith &

Lytle, 2009, p.42). To what extent do participants in the SEI course

develop orientations, knowledge, and skills of LRT teachers? Can they

identify and teach language demands of classroom tasks? To understand

how well participants were prepared to teach language during the SEI

course, surveys and assignments were collected and analyzed from

2013-15.

The SEI course—offered in 4-credit elementary and secondary

versions at our university— is designed to equip teachers with knowledge

and skills to teach the growing population of emergent BLs in

mainstream classrooms. Of 158 course

participants who consented to participate in the study, most were

female, aspiring elementary teachers between the ages of 29-37, and 92%

were native English speakers. Data was collected in the classes of five

bilingual course instructors with significant prior experience working

with BLs in K-12 and higher education in US and international contexts.

Data Analysis

Mixed methods were used to examine teacher preparation to teach

language. Pre and post course surveys were analyzed to better

understand participants’ perspectives of SEI preparation; Specifically,

paired T-tests were conducted using SPSS and open response survey

portions were coded. In addition, five practitioners evaluated

participants’ ability to teach language in a final lesson plan

assignment. I further analyzed lesson plans from my courses to determine

whether language objectives contained language functions and features

and which types of language features were identified. Multiple

viewpoints: practitioners’ and participants’ and mixed methods provided a

comprehensive approach to assessing the influence of the SEI course on

equipping teachers to teach BLs language.

Participants’ Views

Participants felt their ability to identify and teach language

increased in the SEI course. Their survey responses (using a Likert

scale: 1-strongly agree, 2- agree, 3- uncertain, 4- disagree, 5-

strongly disagree) demonstrated a statistically significant change from

the pre-to post survey (See Table 1).

Table 1: Statements regarding participants’ ability to identify and teach language

|

Statements |

Pre-mean |

Post-mean |

Mean change |

t |

p-value |

Direction of

Mean change |

|

I can identify basic

structures and functions of

language. |

2.1 |

1.8 |

-.30 |

3.5 |

*.001 |

Agree to Strongly Agree |

|

I know how to plan language objectives for my classes. |

2.84 |

1.90 |

-.94 |

12 |

*.000 |

Uncertain to Agree |

Participants agreed they could “identify basic structures and

functions of language” and strongly agreed with this statement on the

post-survey. Similarly, on the post survey, participants agreed they

could “plan language objectives for . . . classes.” However, open

responses on the post-survey suggested they would need support to apply

coursework understandings of language in classrooms.

Participants felt they would benefit from more practice

implementing language objectives with real students in classroom

settings. As one student noted, “At this point, I feel like practice is

the best teacher” (emphasis in the original). Similarly, another student

suggested more opportunity to work directly with students during the

course would have been beneficial. And another added, “Since I don’t

have . . . classroom experience, I . . . need . . . support from an SEI

expert [to] help me in a classroom situation.” Participants recognized

the need to receive site-based coaching with real BLs in classroom

settings.

Practitioners’ viewpoints

Practitioners evaluated how well participants identified and

taught language in lesson plans that were drafted, taught, reviewed by

peers, revised then submitted. Lesson components such as: language

objectives, academic vocabulary and language features were rated with a

rubric, as follows: 1 (Unsatisfactory), 2 (Developing Skills), 3

(Proficient), and 4 (Distinguished).

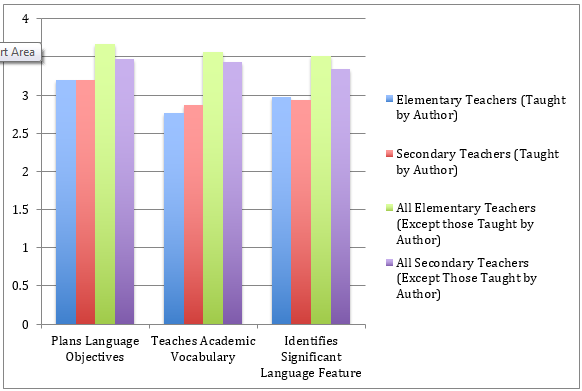

Figure 1: How Practitioners Rated Participants’ Ability to Teach Language

Practitioners felt most participants demonstrated proficiency

in planning language objectives, teaching academic vocabulary and

significant language features. Elementary teachers generally seemed more

skilled at identifying language than secondary participants perhaps due

to prior coursework on teaching reading. In addition, participants

seemed more successful at crafting language objectives than teaching

specific academic vocabulary or language features. That is, they could

identify important academic vocabulary or language features but not

fully demonstrate how to teach them in lessons. As participants

suggested, they would benefit from coaching with real students in

schools to develop facility embedding language-focused instruction

throughout lessons. Finally, I evaluated lesson plans more critically

than other practitioners, demonstrating a need to calibrate our rubric

usage.

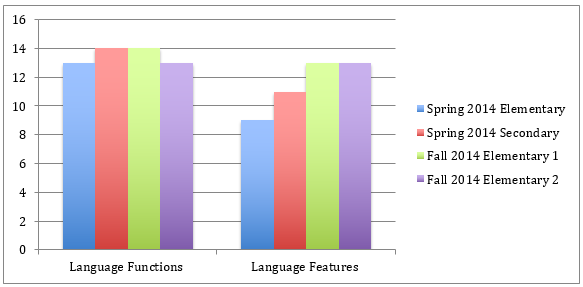

To understand how students conceptualized language in lesson

plans, I also analyzed how 56 students from four course sections that I

taught in 2014 created language objectives, specifically, whether

language objectives contained language functions and features (see

Figure 2), and which types of features appeared in their objectives (see

Figure 3).

Figure 2: Language Objectives: Functions and Features

Most participants included language functions in their language

objectives— how WIDA standards with which students worked throughout

the course are expressed. Participants’ ability to identify language

features increased in subsequent iterations of the course, which I

attribute to instructional improvements not student differences. SEI

course revision has focused on supporting students in identifying and

teaching language features through language objectives, so I also

examined what types of language features were identified in language

objectives (See Figure 3).

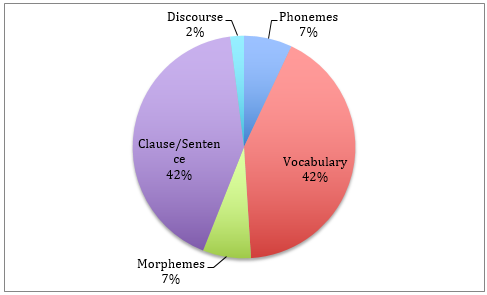

Figure 3: Type of Language Features Identified in Language Objectives

Eighty-four percent of language objectives featured vocabulary

words or grammatical components of clauses or sentences (i.e. parts of

speech). Phonemes or morphemes, such as how to form plurals or create

word families with particular sounds, were a linguistic focus for early

childhood educators, a much smaller subset of participants.

The importance of teaching language demands of content texts

and tasks to emergent BLs has been established (Fang &

Schleppegrell, 2008; Harper & De Jong, 2004). As practitioners,

we became more adept at teaching how to create language objectives over

time. While the SEI course promoted mainstream teachers’ awareness of

their role as language teachers (de Jong & Harper, 2005) and

some ability to create language objectives, participants sought more

support to put language-based teaching strategies into practice in

classrooms. Participants and practitioners agreed: one course is

insufficient. At this point, we seem to be preparing linguistically

aware teachers rather than linguistically responsive ones.

Implications

A coherent approach to preparing linguistically responsive

teachers requires learning to be reinforced in multiple contexts from

coursework to the classroom. Participants recognized the benefit of

language objectives but felt they should have been introduced earlier

and practiced throughout their program of studies. Language knowledge

and skills should be infused throughout teacher education programs,

which requires professional development for all teacher educators.

Participants also sought opportunities to put coursework learning into

practice with real students and receive on-site support, which would

require more coordination between K-12 and higher education settings.

Further practitioner research—studies in both teacher education and K-12

classrooms— are recommended to improve learning opportunities for the

increasing number of emergent BLs taught in mainstream classes in

Massachusetts and beyond.

References

Cochran-Smith, M. & Lytle, S. (2009). Inquiry

as stance: Practitioner research for the next generation. New

York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Cochran-Smith, C & Zeichner, K. (2005). Executive

summary: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education.

In M. Cochran-Smith & K. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying

teacher education (pp. 1-36). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum.

De Jong, E. J. & Harper, C.A. (2005). Preparing

mainstream teachers for English- language learners: Is being a good

teacher good enough? Teacher Education Quarterly,

101-124.

Echevarria, J., Vogt, M.E. & Short, D.J. (2013). Making

content comprehensible for English learners: The SIOP Model

(4th Edition). Pearson: Boston, MA.

Fang, Z. & Schleppegrell, M. J. (2008). Reading in secondary content areas: A

language-based pedagogy. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press. 39-63.

Gibbons, P. (2015). 2nd

Edition. Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: Teaching

second language leaners in the mainstream classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Harper, C. & DeJong, E. (2004). Misconceptions about

teaching English language learners. Journal of Adult &

Adolescent Literacy, 48(2), 152-162.

Kinsella, K. (2011). Linguistic scaffolds for writing

effective language objectives. Unpublished document.

Lucas, T. & Villegas, A.M. (2011). A framework for

preparing linguistically responsive teachers. In T. Lucas (Ed.) Teacher preparation for linguistically-diverse classrooms: A

resource for teacher educators. New York: Routledge.

Santos, M., Darling-Hammond, L. & Cheuk, T. (2012).

Teacher development to support English language learners in the context

of the Common Core State Standards. Understanding language:

Language, literacy, and learning in the content areas.

Stanford University working papers.

Schall-Leckrone, L & McQuillan, P.J. (2014). In J.

Nagle (Ed.) Creating collaborative learning communities to

improve English learner instruction: College faculty, school teachers,

and pre-service teachers learning together in the 21st century. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Schleppegrell, M.J. (2004). The language of schooling:

A functional linguistics perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates.

Uriarte, M. & Tung, R. (2009) “English Learners in

Boston Public Schools in the Aftermath of Policy Change: Enrollment and

Educational Outcomes, AY 2003-AY2006.” The Mauricio Gaston Institute,

University of Massachusetts Boston, MA.

Walqui, A. (2006). Scaffolding instructional for English

language learners: A conceptual framework. The International

Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(2),

159-180.

WIDA English Language Proficiency Standards (2007/2012).

Available at http://www.wida.us

Wright, W. E. (2015). 2nd Edition. Foundations for teaching English Language Learners. Research,

theory, policy, and practice. Philadelphia: Caslon

Publishing.

Zwiers, J. (2014). 2nd ed.

Building academic language: Meeting Common Core Standards across

disciplines, grades 5-12. San Francisco, CA: Jossey- Bass.

Laura Schall-Leckrone is an assistant professor and program director of TESOL and bilingual education at the Graduate School of Education at Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She has worked as a bilingual educator and curriculum director in U.S. public schools. Her research focuses on teacher preparation and pedagogy that promotes critical literacies for bilingual learners. |