|

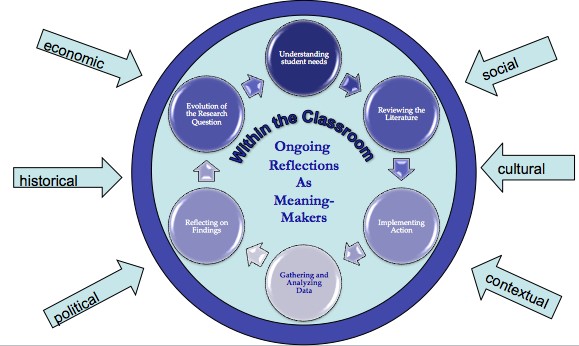

As part of the process of learning to teach and teaching to

learn, our TESOL teacher candidates engage in the development of their

identity from that of a student teacher to a professional educator

through the culminating practicum course where they conduct their

research study. They begin to see that they are central to the

meaning-making process, where they construct meaning and make sense of

their knowledge and experiences as they interact with the broader

contexts, which influence the practice of learning and teaching

(Kumaravadivelu, 2012). Teachers begin to realize that they are not only

enacting what has been transmitted to them, but also taking an active

role in the knowledge generation based on their learning from their

instructional practice. They also begin to understand that they need to

tailor their methods and strategies to suit their students’ individual

and collective needs. Essentially, this shift in identity is from

acquiring pedagogies and practices and employing them directly in the

classroom, to considering the appropriateness or effectiveness of these

pedagogies in light of their students, their classroom context, and the

multitude of external factors. One opportunity provided through our

program, where students can begin to make sense about what it means to

teach students in their particular contexts, is through the cyclical

opportunities provided by engaging in the action research process with

embedded reflective opportunities. We believe that action research is a

cognitively and emotionally demanding task, but a powerful tool for

potentially improving instructional practice.

Figure 1. Shifting identities from student teachers to professional educators

Unpacking Reflective Practice for Teacher Transformation

The wordsreflection, reflective practice, reflective

thinking, reflective judgment, reflexivity, and reflective learning are variations of terms that are

often used in teacher development literature as playing a central role

in teacher transformation (Kember et al., 1999; Mezirow, 1991; Schön,

1990).

Teacher transformation is often referred to as the goal for

teacher education programs, but what this means and how to get our

candidates to this goal remains unclear. Kumaravadivelu (2012) calls for

a reconceptualization of language teacher education in this postmethods

and posttransmission era, where he emphasizes the role of teacher

transformation. This transformation is believed to be achieved by

shifting our teacher candidates to the center of the meaning-making

process and empowering them to mediate their own praxis, analyzing the

theories in their practice and, in turn, having their practice influence

their theories about what it means to teach and learn in their given

contexts.

Fieldwork experiences and practitioner research (Burns, 2010)

have been proposed as tools that support such transformation because of

the reflective opportunities embedded within these experiences (e.g.,

observing, debriefing, journaling, micro-teaching).

But What Does Transformative Learning Really Mean?

According to Mezirow (2003), “Transformative learning is

learning that transforms problematic frames of reference—sets of fixed

assumptions and expectations (habits of mind, meaning perspectives,

mindsets)—to make them more inclusive, discriminating (discernment),

open, reflective, and emotionally able to change” (pp. 58–59).

Take the following riddle for example. A man and his son are in

a terrible accident and are rushed to the hospital in critical

condition. The doctor looks at the boy and exclaims, "I can't operate on

this boy. He's my son!" How could this be?

Most people are often perplexed by this riddle, until their own

assumptions and frames of reference are confronted. The assumption is

often the relationship between gender and profession, where a doctor is

associated with “man.” However, in this case, the doctor is a mother.

Perhaps we might consider that this could have also been a stepfather or

a second father from a two-father home. The reader may have considered

other possibilities as well.

Likewise, through engaging in research, particularly action

research, our candidates are often confronted with a sense of cognitive

dissonance when what they are doing with their students is not leading

to student learning as revealed by what we require, which is the

triangulation of data. We require our candidates to include, at minimum,

three data sets so that their inclination, intuition, assumption, and

proclivity often collected in their teaching journals can be

corroborated by objective counterparts, such as student perceptions,

test measures, and so on. Candidates often come up with project ideas

that they have a certain attachment to, and it is often this attachment

that causes severe disenchantment for them. For example, one candidate

wanted to employ games to teach vocabulary, where it became clear that

her inherent assumption was that the use of games will lead to increase

in vocabulary knowledge and use (however, “games,” “vocabulary

knowledge,” and “vocabulary use” are operationalized for her study). The

results of this study could veer in many directions: (a) vocabulary

knowledge and use increased, (b) vocabulary knowledge and use stayed the

same, (c) vocabulary knowledge and use decreased, (d) vocabulary

knowledge increased, but use decreased, and so on. In addition to a

multitude of variables such as students’ previous background knowledge

and selection of vocabulary, this candidate had to begin to consider

other factors that might have influenced her finding. When she found

that their vocabulary knowledge increased, but not its usage, she

elected to try another game. However, through our discussions, she came

to an understanding that she needed to dig deeper, that it may not

necessarily be the games themselves, but the specific embedded

opportunities that the games provided that led to the results of her

study.

Transformative Learning: How Do We Break Free?

Several processes have been identified in the literature as

providing opportunities for transformative learning. Mezirow (1999)

asserts that when premise is reflected upon and questioned rather than

reflection on content or process, this can lead to transformation.

Likewise, Cranton (2006) describes the questioning of “prior habits of

the mind” (p. 23). Daloz (1999) and Daloz Parks (2000) refer to the

moment when cognitive dissonance is revealed as a “shipwreck moment,”

where Kegan and Lahey (2009) term this as an “optimal conflict” leading

to adaptive change (p. 54). In action research, this often occurs

through the deliberate mediation structures embedded in our

program.

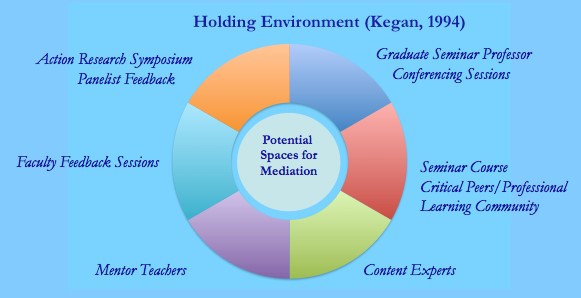

Our Learning Community Based on Sociocultural Theory

Figure 2. Our holding environment

Sociocultural theory has its roots in the work of Vygotsky

(1978), who points out that all learning happens through social

interaction. First the learning appears in the social realm, or the

interpsychological dimension, where teachers or more capable peers

(experts) can scaffold the learning process through the co-construction

of meaning within the zone of proximal development. This learning then

moves from the social level or the interpsychological dimension to the

internal level known as the “intrapsychological category” (p. 128).

Johnson and Golombek (2011) have done considerable work around

reflective learning and teaching and describe the mediation process as

follows: “When we see/hear the same teacher interact with someone who is

more capable while accomplishing a task that is beyond her

capabilities, this creates a window through which we can see her

potential for learning and her capabilities as they are emerging. . . .

[M]ediation in this metaphoric space of potentiality is essential” (p.

6).

We have tried to embed these mediation opportunities in our

holding environment (Kegan, 1982, 1994), with the intention of providing

both support and challenge purposefully negotiated for teacher

candidates’ learning and development. The “expert” others in our program

include not only the seminar professor, but also a critical peer or two

selected from their cohort, content area experts including other

faculty members within and beyond our program, and their practicum

mentor teachers. In addition, candidates engage in feedback sessions

where faculty provide additional feedback on their presentations, prior

to the culminating research symposium where the candidates present their

final research project to a panel of TESOL and other professionals and

receive additional, invaluable feedback.

As such, our program attempts to provide multiple opportunities

for candidates to engage in the type of premise reflection necessary

for teacher transformation to help them make sense of the disconnect or

disenchantment they experience through the process. It remains unclear

what this process entails and what reflection for transformation looks

like given the different knowledge, skills, experiences, and

dispositions students bring with them to the program. As such, a study

is now underway to ascertain how candidates engage in such reflective

practice through a systematic analysis of the mediation process embedded

in the deliberate structures we have put into place to support teacher

transformation in our program.

References

Burns, A. (2010). Doing action research in English

language teaching. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cranton, P. (2006). Understanding and promoting

transformative learning: A guide for educators of adults (2nd

ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Daloz, L. A. (1999). Mentor: Guiding a journey of

adult learners. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Daloz Parks, S. (2000). Big questions, worthy dreams:

Mentoring young adults in their search for meaning, purpose, and

meaning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Johnson, K. E., & Golombek, P. R. (Eds.). (2011). Research on second language teacher education: A sociocultural

perspective on professional development. New York, NY:

Routledge.

Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: Problem and

process in human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental

demands of modern life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (2009). Immunity to

change: How to overcome it and unlock the potential and your

organization. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Kember, D., Jones, A., Loke, A., Mckay, J. Sinclair, K., Tse,

H., . . . Yeung, E. (1999). Determining the level of reflective thinking

from students’ written journals using a coding scheme based on the work

of Mezirow. International Journal of Lifelong Education,

18(1), 18–30.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2012). Language teacher education

for a global society: A modular model for knowing, analyzing,

recognizing, doing, and seeing. New York, NY:

Routledge.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimension of adult

learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2003). Transformative learning as discourse. Journal of Transformative Education, 1(1), 58–63.

Schön, D. A. (1990). Educating the reflective

practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the

professions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The

development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Sarina Chugani Molina serves as assistant professor

and coordinator of the MEd in TESOL, Literacy, and Culture Program at

the University of San Diego. Her research interests include teaching

English as an international language and TESOL teacher development,

particularly as it relates to developing mindful, reflective

practitioners. |