|

In December of 2012, the late President of Uzbekistan, Islam

Karimov, signed Decree 1875, a

measure enacted to promote nationwide foreign language instruction.

Beginning with the 2013–2014 academic year, special focus was given to

English language instruction. To that end, beginning in 2014, all

postsecondary full-time English language teachers with a minimum of 3

years of English language teaching experience were sent to Uzbek State

World Languages University in the capital city, Tashkent, for a 2-month

professional development course. Throughout these 2 months, they

attended seminars on topics such as modern methodology, using technology

in foreign language teaching, and how to plan curriculum and assess

learners. From this point on, every 3 years, teachers will continue to

travel to Tashkent from their home regions to attend these retraining

courses with a view to improving their teaching.

In September of 2017, shortly after my arrival in Tashkent, I

was asked to serve as a consultant for the 2-month retraining period

from 3 October to 3 December. I would observe various training

classes; give feedback on aspects such as

methodology, books, and assessment; and even teach one or two

methodological classes. One of the methodological lessons I presented to

the teachers was a modified, tech-free model of blended learning.

In many countries, the education systems still cling to

teacher-centered methodologies. After teaching in northwestern

Uzbekistan during the 2015–2016 academic year, it was clear that many

teachers in Uzbekistan followed this model. Fortunately, there is a

strong desire for change. The retraining will be continually revised and

improved, striving to show teachers how to use learner-centered

methodologies to teach language. After 2 months, they will return to

their home regions to resume teaching, incorporating what they have

learned into their classes.

Though a learner analysis may include a formal, written

questionnaire, I engaged the trainees in a conversation, making it clear

that their assistance would be used to help me advise the director of

the training center. Not only did I want to provide essential feedback

for the improvement of the teacher training program, but I also needed

guidance for the kind of master class I would teach. These were the

questions:

- Which classes have you taken so far?

- Which ones were the most helpful and why?

- Which ones were the least helpful and why?

Overwhelmingly, the responses were in favor of classes offering

practical application and/or newer teaching methodology. Of the

teachers I asked, none of them liked the classes that were strictly

lecture based.

Smith and Ragan (as cited in Brown & Green, 2016)

designed a five-step learning task analysis, which is what I used to

design my Station Rotation Task. The steps are:

- Write a learning goal.

- Determine the types of learning of the goal.

- Conduct an information-processing analysis of the goal.

- Conduct a prerequisite analysis and determine the type of learning of the prerequisites.

- Write learning objectives for the learning goal and each of the prerequisites.

In addition to the questions asked of the teachers, I

also spoke to some of the teacher trainers to ascertain what kind of

instruction the learners needed, employing these trainers as unofficial

subject-matter experts. Most commonly, I was asked to show teachers

methods that emphasized differentiation in the English language

classroom, teaching multilevel classes, and new methodology that would

enable teachers to teach learner-centered classes.

Blended learning is an educational model that combines online

and offline instruction. (Blended Learning 101

Handbook, 2013). I designed my master class to show the

Station Rotation Model, a blended learning model that I first learned

when I was in my early years as an English language teacher. In this

model, learners in a classroom are divided into small groups. There are

three or four learning stations, each one focusing on a different

activity. After the allotted time set by the teacher, students will move

to another station. This continues until all students have visited each

station. The instructional portion is explained in detail in another

part of this article, but the general organization of my master class

was as follows (Figure 1):

Figure 1. Master class organization.

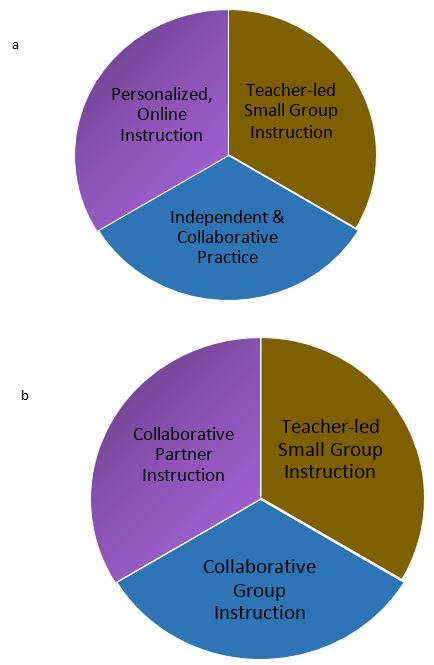

One of the limitations in Uzbekistan currently is the lack of

internet access in classrooms, even at top universities in the nation.

Therefore, while the traditional Station Rotation Model would include

online and offline learning (Figure 2(a)), it was necessary to modify

the model to reflect the realities of a language classroom in Uzbekistan

(Figure 2(b)).

Figure 2. Traditional Station Rotation Model (a) and modified version for Uzbekistan (b).

Teachers were interested in learning new methodology. Though

most teachers had heard of the blended learning concept, only some could

define it—but even they did not know how to use it in their own

classrooms. Rather than simply talking about Station Rotation, it was

important to show them how it worked in the classroom, providing them

with a new way to teach their students once they returned to their home

region.

After designing the learning model (see Figure 1), I designed

the lesson with the following instructional objectives:

- After participating in a practical application of modified

blended learning, teacher trainees will be able to accurately identify

the components of the Station Rotation Model without error.

- Given examples of the Station Rotation Model of blended

learning, teacher trainees will be able to construct their own model

with 80% accuracy.

The training module took place during an 80-minute class. To

demonstrate how the blended learning model works, I chose a simple

lesson on the parts of speech. Borrowing from something one of my

graduate school professors did, I begin with practical application. For

the first 30 minutes, teachers acted as students and I was the only

teacher in the room. Participants were divided into small groups,

working at three different stations. After 10 minutes, they moved to

another station (see Table 1).

Table 1. Station Rotation Model Example, Part 1 (Practical Application)

|

10:10 am–10:20 am |

10:20 am–10:30 am |

10:30 am–10:40 am |

|

Group 1 |

Practice Activity – partner work (parts of speech worksheets) |

Practice Activity – small group (story blanks/write a group story) |

Teacher Station (teaching content) |

|

Group 2 |

Teacher Station (teaching content) |

Practice Activity – partner work (parts of speech worksheets) |

Practice Activity – small group (story blanks/write a group story) |

|

Group 3 |

Practice Activity – small group (story blanks/write a group story) |

Teacher Station (teaching content) |

Practice Activity – partner work (parts of speech worksheets) |

After 30 minutes, the practical application stopped and we

began discussing what teachers noticed and the theoretical foundations

for the model. Teachers responded to questions as to what they

(students) were doing, what I (teacher) was doing, and where were the

best stations for lower and upper level students to begin.

During the final part of the training module, teachers remained

in their groups but were now required to create a new Station Rotation

Model for a specific skill. They were given the choice of listening and

speaking, reading, or writing. After each group chose their skill, they

were given 10 minutes to design a workable model for their classroom.

Then, each group presented its model to the entire class, with audience

members critiquing what did or did not work.

Twelve learners engaged in the instruction. The practical group

work served as an informal, formative assessment, allowing me to

discern whether the participants understood how the model worked. As we

concluded the lesson, I conducted an informal summative assessment,

asking the teachers whether this was something they could realistically

do in their own classrooms. One teacher commented on how useful it was

to ask them to build the model based on what I had demonstrated. Other

teachers gave me private feedback. One 30-year teaching veteran told me

that the other teachers in her class view her as an expert. Yet, she

said that after my lesson, she realized there was much for her to learn

still, despite her many years of teaching. Unfortunately, there will be

no way for me conduct a long-term summative assessment to discover

whether teachers will use this method in their classrooms. At the

writing of this project, they have all returned to their home regions,

and I will shortly return to the United States.

References

Aspire Public Schools. (2013). Blended learning 101:

Handbook (1st ed.). Retrieved from http://aspirepublicschools.org/media/filer_public/2013/07

/22/aspire-blended-learning-handbook-2013.pdf

Brown, A., & Green, T. (2016). The essentials

of instructional design: Connecting fundamental principles with process

and practice (3rd ed.). New York, NY:

Routledge.

President resolves to improve foreign language learning system.

(2012, December 11). Uzbekistan National News Agency. Retrieved from http://uza.uz/en/society/president-resolves-to-develop-foreign-language

-learning-system-11.12.2012-3147

Rebecca Martin has been teaching English since

2010. She recently spent 2 years in Uzbekistan as an English Language

Fellow, a program funded by the U.S. Department of

State. |