|

In preservice teacher education, curriculum design is critical for helping prospective educators “[make] a plan of activities, [formulate] general provisions, [and determine] the goals” (Korotchenko, Matveenko, Strelnikova, & Phillips, 2015, p. 214) of their respective classes and instructional units. Indeed, without appropriate designing and planning strategies, instruction can be ineffective in fostering students’ understanding of new knowledge as well as the linguistic resources that aid in sense-making (Gibbons, 2015). A purposeful curriculum should therefore provide students with opportunities to connect new information with prior knowledge through interaction and shared experiences as well as contextualized scaffolding of language demands.

Such work requires a paradigm shift for new educators who may feel heavily dependent on the structure of available resources and not confident enough to adapt instruction to students’ needs (Hodaeian & Biria, 2015), especially along the lines of language. The backward design approach has proven useful for curriculum planning (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005), however, and has informed how we train preservice teachers to build curricular units with language in mind in the general education classroom.

The purpose of this article is therefore to present our process of designing curricula with preservice teachers in an effort to scaffold their understanding of the different aspects of a curricular unit as well as how to integrate a focus on language into each component. As such, we begin by providing a brief overview of backward design and our teaching context before explaining our curriculum-building process.

Backward Design Approach

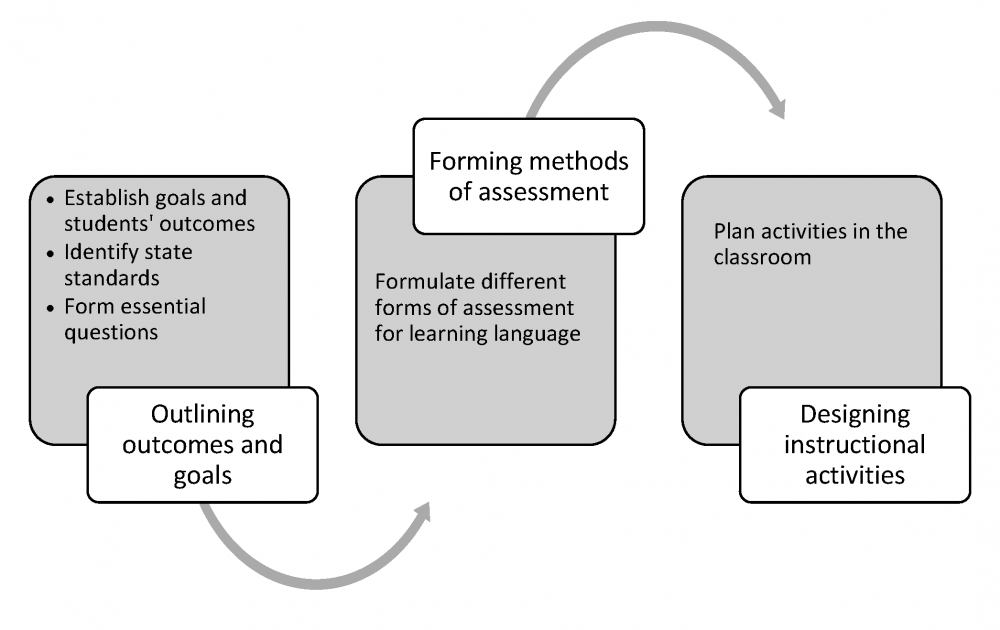

As described by Wiggins and McTighe (2005), backward design is an approach that centers on goal-setting and learning outcomes prior to the creation of instructional activities and assessments. In other words, educators need to know what, specifically, they want their students to learn and achieve before planning individual lessons. Accordingly, this approach includes three stages as illustrated in Figure 1: outlining outcomes and goals, forming methods of assessment, and designing instructional activities.

Figure 1. Backward design process (adapted from Wiggins & McTighe, 2005,p. 18).

Teaching Context

The course in which we use backward design is for elementary preservice teachers serving English learners (ELs) in the general education classroom. Because this course, titled Language and Culture in the Classroom, is one of the first that they take as part of their program of study, few are familiar with how to create lesson plans let alone a larger instructional unit. Thus, we use backward design to introduce them to the different parts of a curriculum and to support them in developing the language-specific goals and tasks of their own units. Additionally, we require them to create units on a genre-based writing project since a focal point of our course is on how to help ELs develop their speaking, listening, reading, and writing skills.

Application of Backward Design

To begin the backward design process, we ask the preservice teachers to consider what the overarching goals of their curricular units are and what, explicitly, they want their students to be able to do with language to achieve those goals. As illustrated in Table 1, which details the design of a curricular unit for a third-grade procedural writing project, this initial step also involves determining the unit’s essential questions based on the enduring understandings students will work toward to support their transfer of knowledge. Notice that the language objectives of the unit (e.g., use of connectives, present tense action verbs) are a result of the type of writing students will be learning to produce. In other words, at the outset, our aim is to help the preservice teachers move beyond a focus on vocabulary to more purposeful and contextualized language learning tasks.

Table 1. Step 1: Outlining Outcomes and Goals

|

Curricular Unit Components |

Detailed Information |

|

Unit goals and outcomes |

Students will be able to write a procedural text that explains how to do something (e.g., cooking).

Students will be able to organize their writing by stating the goal and steps needed to carry out their procedure.

Students will be able to use connectives in their writing (e.g., first, then, next).

Students will be able to use present tense action verbs in their writing |

|

State standards |

ELAGSE3W2: Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly. |

|

Enduring understandings and essential questions |

How do we write a procedural text? |

In the second phase of the backward design process, which can be viewed in Table 2, the preservice teachers determine how they will assess whether their students achieved the desired goals of their unit. This step includes identifying a final performance task (e.g., write a procedural text) as well as the types of evidence that will be collected throughout the unit to determine what students know and are able to do. Notice that because the goals and objectives of the unit involve using particular linguistic and structural features to write a procedural text, the modes of assessment evaluate students’ ability to do just that (e.g., quiz on sequencing).

Table 2. Step 2: Forming Methods of Assessment

|

Curricular Unit Components |

Detailed Information |

|

Project |

Write a procedural text that shows how to do something |

|

Quiz |

Quiz on sequencing through language (i.e., put the instructions in the correct order) Fill-in-the-blank worksheet (i.e., use the appropriate action verbs to complete the recipe). |

|

Informal assessments |

Classroom discussion: ingredients of cookies. Group presentation: recipe for making another type of cookie. |

In the last phase of the backward design process, the preservice teachers are encouraged to engage in instructional planning. An important step in this process is to identify the type of goal associated with each activity. Wiggins and McTighe (2005), for example, stress the importance of activities that allow students to make meaning and not only acquire new knowledge but transfer it as well. As can be seen in Table 3, all three goals are met through the application of the teaching-learning cycle, which is a pedagogical framework for scaffolding genre-based writing (Rose & Martin, 2012). Notice also that the objectives identified in the first phase of the curriculum design process are realized through these activities, too, as each one is implemented to scaffold students’ understanding of a procedural text. In particular, they focus on how to use particular linguistic and structural resources to produce a similar text collaboratively (e.g., a recipe for another type of cookie) and a slightly different one individually (e.g., transferring knowledge to a new context by writing a procedural text on something other than cooking).

Table 3. Step 3: Designing Instructional Activities

|

Curricular Unit Components |

Detailed Information |

|

Building the field |

Students will taste cookies to determine what ingredients were used. Students will then brainstorm how the ingredients came together to make the cookie they are tasting.

(Meaning-making) |

|

Deconstruction |

Teacher will help students break down a procedural text for chocolate chip cookies by focusing on how the text is structured as well as what kind of language is used to create a clear set of directions

(Acquiring) |

|

Joint construction |

Students will work in groups to write a procedural text (i.e., a recipe) for making another type of cookie)

(Meaning-making, Acquiring) |

|

Independent construction |

Students will work by themselves to write a procedural text that explains how to do something rather than cooking (e.g., building a treehouse)

(Transferring) |

Conclusion

In our experience, preservice teachers often rush to application with little consideration of how their instruction aligns with the goals of their curricular units. Additionally, as it relates to foregrounding language in their instruction, there is often a mismatch between the language identified as important and the language actually needed to engage in contextually-driven speaking, listening, reading, and writing tasks. With the use of backward design, however, many of these issues can be resolved given that the approach demands that preservice teachers first identify the goals of their curricular units and then carefully plan how those goals can be met through different modes of assessment and instruction.

References

Gibbons, P. (2015). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: Teaching English language learners in the mainstream classroom (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hodaeian, M., & Biria, R. (2015). The effect of backward design on intermediate EFL learners’ L2 reading comprehension: Focusing on learners’ attitudes. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research, 2(7), 80–93.

Korotchenko, T. V., Matveenko, I. A., Strelnikova, A. B., & Phillips, C. (2015). Backward design method in foreign language curriculum development. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 215, 213–217.

Rose, D., & Martin, J. R. (2012). Learning to write, reading to learn: Knowledge and pedagogy in the Sydney school. London, England: Equinox.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Khanh Bui is a doctoral student in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia. His research interests are social semiotics, multimodality, and ESOL mathematics education.

Nicole Siffrinn is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia. Her research interests include social semiotics, disciplinary literacy, and preservice teacher education. |