|

Laura Hamman

|

|

Rui Li

|

|

Rachel Manley

|

Introduction

Discourses of globalization, centering on global flows of

information, people, and resources, have become increasingly prominent

in educational literature. These conversations are especially relevant

for English language learners (ELLs) who regularly move within and

across geopolitical and ideological borders. Many education scholars

have begun exploring the role of multimodal communication and digital

media in maintaining and extending borders, including possibilities for

fostering “critical cosmopolitanism” (Hawkins, 2014), which not only

considers global encounters, but, further, addresses ethical,

intellectual, and performative aspects of this type of

interconnectedness.

Cosmopolitanism is far from a new concept; scholars trace its

origin to ancient Greece where, in the 4th century BC, Diogenes deemed

himself a “kosmou polites,” or a citizen of the world

(Ong, 2009). This idea was reaffirmed during the Enlightenment era and

has been taken up across disciplines, largely as a political theory;

more recently, cosmopolitanism has extended into the social sphere to

consider the implications of increased global interconnectedness

(Delanty, 2006). However, scholars such as Hawkins (2014) argue that

existing literature on cosmopolitanism has not sufficiently engaged with

issues of power and privilege. Bringing the concept to bear on

education, she calls for a “critical cosmopolitan education” that

explicitly engages with social justice.

At the 2016 TESOL convention, we employed this critical lens to

consider how learning environments in classrooms and community-based

sites might be designed to expand understandings of learning, literacy,

and globalization. We presented findings from three studies that explore

how digital technology and communication shapes students’ development

of a critical cosmopolitan stance. In the first study, the author

examined the use of technology-enhanced learning environments to support

literacy and global awareness among adolescent ELLs. In the second, the

author shared findings from Global

StoryBridges, an afterschool program for preadolescent ELLs

that connects students through digital storytelling. In the third, the

author explored how digital tools fostered critical reflection for

preservice teachers who were teaching abroad. Together, these studies

provide a consideration of critical applications of digital technology

for ELLs and their teachers.

Literacy, Learning, and Globalization:

Technology-Enhanced Learning Environments for Youth

Rachel Manley

The qualitative study I presented examined the affordances and

challenges of using technology-enhanced learning environments to support

literacy and global awareness among youth in out-of-school contexts. I

was particularly interested in finding evidence of critical

cosmopolitanism while youth engaged in cross-cultural communication.

There were five participants, ages 9–11, all nonnative English speakers.

In this 6-week project, they engaged in cross-cultural interactions

through the ePals

website. They created and exchanged artwork, photos, and

videos and participated in online discussion forums with students from

Romania and Namibia. My data sources included observations, artifacts

(artwork, photos, movies), and student interviews.

I found two main patterns of understanding: making connections

and making comparisons. Making connections and comparing cultures were

common and consistent ways in which students made sense of transnational

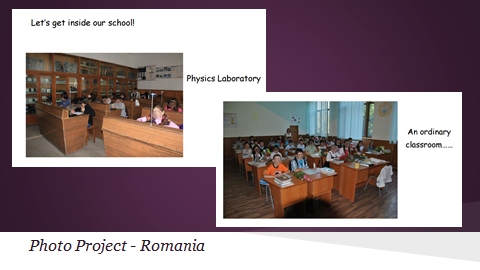

communication. For example, the U.S. students viewed a photo tour of a

Romanian school. The discussion that followed showed evidence of

students making connections and comparisons with their experiences (see

Figure 1). Making connections allowed learners to see the broader global

context of their interactions, while making comparisons situated

students in relation to global others. These ways of understanding are

indicators that students are engaged in cosmopolitan practices and

working toward more globally conscious selves.

Figure 1. U.S. students’ discussion of Romanian school photo tour

The findings from interviews suggest a shared belief in the

importance of cross-cultural communication and global awareness among

students and staff at the community center. Some learners expressed

their desire for more general knowledge about other cultures, while

others argued that global awareness is necessary for successful

cross-cultural interactions and relationships. As one student explained,

“It is important to learn about

how people are the same and different from you, and what their lives

are like.”

Digital Stories as Global Bridges: Language, Culture, and Critical Cosmopolitan Education

Rui Li

This study explores how digitally-mediated learning in

community-based sites can amplify understandings of language and

culture. Global

StoryBridges is an afterschool program created by Professor

Margaret Hawkins that uses digital storytelling to link global ELLs

(ages 11–12) living in poverty. Using iMovie and Flip cameras, youth

collaboratively create and share digital stories with global peers. They

also post and answer questions (in English) regarding others’ videos

posted on the project website. The project aims to provide equal access

to digital transnational communication and to foster social justice

(Hawkins, 2014). As the project coordinator, I examined how children

engaged with digital storytelling and transnational communication

reconstruct their cultural and linguistic worlds. Approaching this

critically, I explored how project activities illuminate issues of

power, status, and privilege.

From my data analysis, I found that the project provided space

for learners to explore cosmopolitan identities through conversations

about language. For instance, after the Ugandan children posted a video

in which they sang hymns in Luganda, their local language, the students

from the Chinese site asked, “What language was your song?” and students

from the U.S. site (also ELLs) commented, “Do you try to teach your

parents English? Sometimes we try to teach English to our parents, but

they still talk Spanish.” Language ideologies also emerged in the recent

“Winter Solstice” video, created by the Chinese children in written and

spoken English (see Figure 2). When U.S. children heard the accented

English in the video, they asked, “Can they speak English?” These

inquiries have inspired me to rethink language and privilege, prompting

new questions. Namely, whose English is legitimized? Whose language is

privileged and whose is ignored?

Figure 2. Chinese students’ video “Winter Solstice”

My broader findings show that ELLs can become critical

knowledge designers, producers, and transformers through collaborative

digitally-mediated, transnational communication. By integrating texts,

images, audio and other multimodal resources, students developed

critical understandings of their imagined worlds (Hull & Katz,

2006). Thus, I argue for critical multimodal

cosmopolitan education for ELLs, one that redefines “knowledge” and

“learning” in the digital era to value children’s multiple repertoires

beyond language and that reconceptualizes equitable human

relationships.

Fostering Critical Reflection With Preservice Teachers

Laura Hamman

In my study, I explored how digital tools shape preservice ESL

teachers’ reflections and foster critical cosmopolitanism. I was

particularly interested in the experiences of undergraduates who were

student teaching in low-income communities in Mexico and Uganda. This

project developed out of my own interest as their elementary ESL methods

instructor. There were seven participants in the study, all of whom

were women and most of whom were White. The digital artifacts included

students’ weekly blog posts, course discussion posts, and summative

digital stories. Participants were interviewed twice in focus

groups.

After analyzing interview data, three themes emerged as

contributing to critical reflection: authenticity, autonomy, and

audience. Authenticity was an important element of the digital stories,

which were, in the words of one participant, “a good format for just

authentic talking about what people are feeling and thinking.” Through

digital stories, dispositions of critical cosmopolitanism emerged, which

included viewing all students as capable, engaging in critical

self-reflection, and developing caring toward global others.

Autonomy was salient in students’ discussion of their

individual blogs, a space to freely grapple with issues—unlike the more

structured discussion prompts. One participant, Rebecca, explained that

her blog was about “more than just those random experiences…like

safaris…I wanted it to actually reflect what I was thinking about my

experiences…” In one entry, she critically reflected upon constructions

of race and identity, interrogating the ways her Ugandan students

understood “being American”:

These moments have just made me

think of the “single” stories that I would say some of my students, if

not all, have seen, experienced, and heard about Whiteness. How many

teachers from Canada, Australia, and America have they had come to them?

How many were White? How many were of African descent? What about the

tourists they have seen? What were they like? What did they look like?

What about the media? Granted my student’s [sic]

favorite musicians are majority Black-American, but how else have they

been inundated with a single story of what it means to be American. From

what I’ve heard from my students it seems pretty white washed.

(Rebecca, 2015, October 3)

Finally, students described the importance of having a

meaningful audience. Jamie shared her blog with family and friends,

“putting it in a way that was relevant or understandable for people who

are outside of the education field.” Another participant played her

digital story at her graduation party. Because the digital story and

blog embodied the “3 A’s” (authenticity, autonomy, and audience), they

transcended the classroom and provided students with a platform for

engaging with critical cosmopolitanism perspectives in a way that the

structured discussion board did not. Thus, I believe that digital

technologies aimed at fostering critical cosmopolitanism should be

designed to provide authentic and autonomous spaces for reflection, with

a format that facilitates sharing emerging understandings.

Conclusion

These brief summaries reveal different ways to engage with

digital technologies to foster critical cosmopolitanism. Manley’s

project showed how making connections and comparisons with global others

is an important first step in achieving critical cosmopolitanism. Li demonstrated how language ideologies emerge through digital

storytelling, providing a platform for critical conversations. Finally,

Hamman revealed that certain conditions should be met for critical

reflection to emerge from digital technology; namely, the tool itself

must promote authenticity, provide autonomy, and have a meaningful

audience. We argue that each of these projects demonstrates how students

are approaching critical cosmopolitanism and that

further research is needed to explore how digital technology can be

leveraged to deepen students’ understanding of the world and foster

socially just attitudes and actions toward global others.

References

Delanty, G. (2006). Cosmopolitan imagination: Critical

cosmopolitanism and social theory. Journal of

Sociology, 57(1), 25–47.

Hawkins, M. R. (2014). Ontologies of place, creative meaning

making and critical cosmopolitan education. Curriculum

Inquiry, 44(1), 90–112.

Hull, G. A., & Katz, M.-L. (2006). Crafting an agentive

self: Case studies of digital storytelling. NCTE, 41(1), 43–81.

Ong, J. C. (2009). The cosmopolitan continuum: Locating

cosmopolitanism in media and cultural studies. Media, Culture

& Society, 31(3),

449–466.

Laura Hamman is a PhD candidate at the University of

Wisconsin-Madison. Her dissertation research explores the role of

translanguaging practices and pedagogies in dual language immersion

classrooms. Laura teaches courses in ESL methods, SLA, and educational

linguistics, and she supervises teachers obtaining ESL

certification.

Rui Li is a PhD candidate at the University of

Wisconsin-Madison. Her research focuses on global youth engagement with

multilingual and multimodal learning and identity formation through

transnational media.

Rachel Manley taught for 8 years and now works as a

project coordinator for iEARN-USA. She completed her MEd at the

University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her professional interests include

understanding how technology-enhanced environments can improve literacy

and understanding of global others. |