|

The increasing sophistication and ease of Internet-based

conferencing tools such as Skype pose a tremendous challenge to foreign

language educators. Such tools create new opportunities for students,

offering them “precious opportunity to practice foreign languages with

native or near native speakers on the Internet” (Elia, 2006, p. 30).

Foreign language instructors who sense this often lack ideas of what to

do with it. As an American instructor of Japanese in a U.S. university

and a former ESL instructor in Japan, I have been interested in using

virtual encounters to create back doors for students from both countries

to build meaningful relationships through both English and Japanese.

Using Skype to become acquainted with incoming students of English from a

sister university in Japan is one such illustrative case that has

reaped benefits far beyond the initial encounter.

Setting

My institution is a mid-sized state university with a Japanese

language enrollment in the range of 110 to 130 students per semester;

however, the number of undergraduate Japanese nationals is currently

only five, a number that has rarely been exceeded in the last 10 years.

Of the five students from Japan, four are exchange students from two

official Japanese sister universities. At any one time, one to three

home university students are also sent as exchange students to the

Japanese sister universities.

In the spring before the current academic year, I reached out

to the four incoming exchange Japanese students, obtaining their contact

information from the previous year’s cohort of exchange students that

was winding up their year on my campus. I asked the incoming students if

they could meet me and any interested students of Japanese over Skype.

As part of the home students’ grade in Japanese, they had to attend at

least two events relating to international culture sometime during the

semester. At least one of the events had to relate to Japan. This Skype

session counted as one such event.

Approximately 10 home students and 3 exchange students

participated on the U.S. side. Due to the difficulty of arranging a time

convenient to all four of the incoming students from Japan, we could

only connect with two of them, both from the same sister university;

however, all four had already begun communicating with home students of

Japanese, albeit mostly in English, through a Facebook group that I

created for them. The two new exchange students participating in the

Skype session were joined by two home university students then studying

Japanese at that sister university. The four students on the Japan side

connected to Skype from the apartment of one of the students. On the

U.S. side, I met with the students in a conference room where I used my

personal laptop and its built-in webcam and microphone. Our Internet

connection was through the campus wifi network. The laptop was then

connected by a VGA and audio cable to a larger wall display with

speakers (see Figure 1).

The session was scheduled for 30 minutes, although I allowed

extra time at the end in case students wanted to keep talking, which

they did for another approximately 30 minutes. While my experience and

that of others using videoconferencing for language instruction suggest

that “the mere existence of services such as Skype is not enough to

benefit language learners in an organized, structured way” (Mullen,

Appel, & Shanklin, 2009, p. 102), in this particular Skype

session, I had no agenda other than to meet and greet, and to do so for

the first half in Japanese and the second half in English. On the U.S.

side, two then-current exchange students from the same Japanese sister

university, and on the Japan side, the two home university students and

two incoming exchange students had all known each other for at least the

previous 6 months, so the situation was already friendly and familiar,

and I did not consider it necessary to introduce any particular

structure to the session. However, at the beginning of the session, I

made a short introduction in Japanese and asked a few starter questions

to all students until the conversation got going on its own momentum.

Because the incoming students’ level of English far surpassed the home

students’ novice level of Japanese, in the first half of the session in

Japanese, I prompted the home students to begin with basic information

they could handle from their Japanese classes, such as name, year in

school, major, hometown, leisure activities, and favorite things. When

we switched to English, we moved to more practical information that

would be useful for the incoming students.

To give the Japan side an idea of our physical surroundings, I

unhooked the cables from the laptop and took it out into the hallway,

using the laptop on battery as if it were a person we were leading

around (see Figure 2). As the students and I narrated what we were

showing, we then walked to the outside of the building, which was the

fourth-floor balcony that surrounded the building. Careful to aim the

webcam horizontally and to not make sudden movements, I walked around to

the other side of the building with the laptop, giving the Japan side a

360-degree unobstructed view of the campus and city (see Figure 3). We

then returned to the conference room where we started.

Follow-Up

Although the session required some logistical work ahead of

time, the lack of an agenda and the playful stance toward the webcam

gave this a free, impromptu feel. The event helped the two incoming

exchange students make new friends before arriving on campus in the

fall. In describing much more elaborate and sustained telecollaboration

projects, Allen and Dupuy (2013) point to the potential that such

projects have to create friendships; however, they add that “unknown is

whether these online friendships endure beyond the course in which they

developed and, if they do last, their role in facilitating students’

development of social networks once abroad” (p. 481). This is where an

instructor can facilitate both the opportunities for friendships to

develop and the maintenance of friendships once started.

Three of the students who participated in the Skype session

also participated in a study abroad trip that my Japanese teaching

colleague and I led to Japan that summer. During the trip, we made a

point to visit the university of the students in the Skype session, and,

when we arrived by bus into the city where the university was located,

the two students were eagerly waiting to greet us. Because of the Skype

session a few weeks prior, we required no activity to “break the ice,”

but instead quickly and excitedly picked up our relationship where we

had left off. As they did in the Skype session, our two hosts graciously

spoke Japanese to our students at first, but as the conversation became

more complex, they adroitly transitioned to English.

For 3 days, the new exchange students spent all their free time

showing us their campus and city. A few days after the visit to that

city, I had arranged a get-together in a Tokyo izakaya (a Japanese-style pub) for my university’s

past and current students in Japan. There, we met the other two incoming

exchange students who could not participate in the Skype session. The

Japan trip served, among many other things, as an extra opportunity to

see “these online friendships endure.” After our Japan trip, when the

new exchange students arrived in our U.S. city, our students and I were

excited to go to the airport to welcome them, drive them to campus, help

them settle into their dorms, and take them to a restaurant for a

welcome dinner. (As my department had no funds for this, I paid for the

four exchange students’ meals myself.)

The exchange students quickly became close to the home

students. The former are thus disinclined to associate mainly with their

own nationality, as happens all too commonly among international

students. Both groups, the Japanese exchange students of English and the

home students of Japanese, are seen on campus as one big group, which,

from anecdotal evidence, contributes to the home university’s growing

enrollment in Japanese.

Language as a Community Builder

Beginning in the 1990s, the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages developed a set of standards for foreign language instruction primarily in K-12 schools (ACTFL, 2006), although it has become influential at the U.S. postsecondary level as well. The standards task force identified five goal areas, which it termed "the five C's," for foreign language education (p. 31): communication, cultures, connections (to additional bodies of knowledge), comparisons (and contrast with students' own language and culture), and communities (of language users at home and abroad). Using language

learning to form satisfying relationships comes under this last goal

area of “communities,” which includes two standards: “Students use the

language both within and beyond the school setting” (p. 64) and

“Students show evidence of becoming life-long learners by using the

language for personal enjoyment and enrichment” (p. 66). Buried within

the second standard is one of many sample progress indicators, this one

specifically for Grade 12: “Students establish and/or maintain

interpersonal relations with speakers of the language” (p. 67).

While making friends may seem an obvious point of language

learning, “at times, the professional literature portrays implementation

of the Communities standard as an extra-curricular experience, like a

field trip” (Magnan, 2008, p. 360). Even language teachers who

diligently strive to create communicative experiences in their

classrooms can too easily forget that, for much of the general public,

“participation in multilingual/multicultural communities [is] the raison d’être for foreign language study” (Phillips,

1998, as cited in Magnan, 2008, p. 359). More often than not, that

community is close at hand, eager to be tapped and brought into the

larger community. When that community does not happen to be in the

physical vicinity, the prevalence and ease of use of communication

technologies such as videoconferencing allow for the community to be

formed and nurtured, motivating that community to come physically face

to face at some point in the future.

Seen from one perspective, the outreach to Japanese exchange

students to create a Japanese and English language community is simply

extra work, none of which is compensated. The happy adjustment of

exchange students is nice, but is the responsibility of the division

responsible for international students, hardly that of the foreign

language faculty. However, even from a cold instrumental standpoint,

that extra work pays off with helpful, albeit unquantified, dividends.

All of the exchange students are more than happy to show their gratitude

by assisting me and my colleague in teaching Japanese class when their

schedules permit and by assisting students with their Japanese study

outside of class. When native speakers are present for language

activities in the classroom, those activities are suddenly more

interesting and real. Moreover, the extracurricular friendships formed

through this community building give students a flesh-and-blood reason

to learn the language of the other, which can only increase students’

motivation for learning. If community is to be genuinely considered a

goal in language learning, then the instructor can be a pivotal force

for forming it and keeping it vibrant. Communication technologies such

as Skype are powerful tools which, with some forethought and legwork,

can greatly aid that endeavor.

References

Allen, H. W., & Dupuy, B. (2013). Study abroad, foreign

language use, and the communities standard. Foreign Language

Annals, 45, 468–493.

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. (2006). Standards for foreign language learning in the 21st

century. (3rd ed.). Lawrence, KS: Allen Press.

Elia, A. (2006). VOIP and Skype: A new frontier of online

language learning. IATEFL CALL Review, Summer,

30–34.

Magnan, S. S. (2008). Reexamining the priorities of the

national standards for foreign language education. Language

Teaching, 41, 349–366.

Mullen, T., Appel, C., & Shanklin, T. (2009).

Skype-based tandem language learning and Web 2.0. In M. Thomas (Ed.), Handbook of research on Web 2.0 and second language

learning (pp. 101–118). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

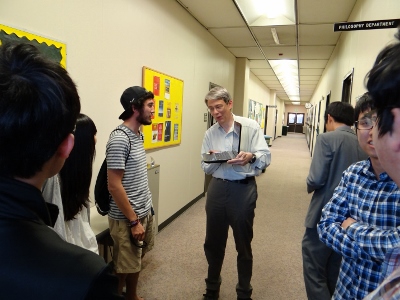

Figure 1. Author and U.S. home university

students connect with Japanese sister university students through

Skype.

Figure 2. Author takes laptop into hallway

and points its built-in webcam to students to talk.

Figure 3. Author points his laptop webcam to

his campus and city to show incoming Japanese sister university

students their new environs.

Tim Cook is an adjunct instructor of Japanese at the

University of Alabama at Birmingham. He is the only person to hold an

Emmy for teaching, an accolade he received for teaching Irasshai, a

Japanese language instructional program from Georgia Public

Broadcasting. He holds a PhD in mass communication from the University

of Alabama and an MAT in ESL/EFL from the School for International

Training in Brattleboro, Vermont. Cook was also recognized as a master

folk artist by the Alabama State Council on the Arts for teaching

shape-note singing, an early American a cappella tradition preserved

mainly in rural churches in the American South. |