|

Despite many teachers agreeing that pronunciation training is

important for learners, it has long been neglected in language

classrooms (Murphy, 2014). Teachers report feeling uncertain about how

best to teach it and also often note that there is little classroom time

available for its instruction. Others believe that communicative

language teaching is incompatible with focusing on the form of

pronunciation, and so avoid it altogether (Isaacs, 2009). The net result

is that when pronunciation instruction does happen, it is often

incidental, primarily occurring in the context of particularly egregious

breakdowns in communication.

Given these limitations and learners’ need for massive amounts

of exposure and practice in order for more accurate pronunciation to

develop, computer-assisted pronunciation training (CAPT) seems like an

obvious complement to traditional classroom instruction. Not only can

CAPT help raise learners’ awareness of English pronunciation features,

but it also allows for the large-scale exposure and practice that is

necessary for improvement.

Unfortunately, relatively few pronunciation software

applications are available, and those that do exist are not always

evidence-based (Derwing & Munro, 2015). Good pronunciation

software should be capable of addressing individual differences in

learning. So, for example, applications should be customizable to the

specific needs of learners from particular first-language backgrounds.

They should also be capable of focusing learners’ attention on sounds

rather than only on words (Thomson & Derwing, 2016).

English Accent Coach

One such program is English Accent Coach (EAC; www.englishaccentcoach.com),

a free web-based application that allows learners to autonomously

develop their perception of English vowels and consonants. The name of

the website reflects terminology used by end-users who search for it,

rather than intending to imply that foreign accents are problematic. In

fact, the aim of this application is to improve speakers’

intelligibility, not global accent.

EAC follows the High Variability Phonetic Training paradigm

(HVPT). This technique is not as complex as its name makes it sound.

Essentially, HVPT refers to a type of perceptual training that presents

learners with training stimuli in numerous phonetic contexts, spoken by

different talkers. It can be roughly conceived of as minimal pairs on

steroids. Laboratory research has repeatedly demonstrated that this

technique is more effective than traditional practices, in which training stimuli are spoken by a single

talker, or in which training exercises focus on sounds in a limited

number of contexts (Thomson, 2011). Unlike a simple minimal pair approach, HVPT promotes

the extension of perceptual learning during training to new talkers and

to new items. HVPT has also been shown to promote transfer of

perceptual training to production (see Thomson, 2011, for a detailed

overview).

EAC takes HVPT out of the laboratory and makes it available to

learners on a large scale. Because the application is web-based, it can

be used at learners’ leisure, as long as they have access to a computer

with a high-speed internet connection, and a quiet space. EAC allows

learners to focus on individual areas of difficulty in perceiving

English vowels and consonants. Preset levels promote learning of target

sounds in increasingly complex contexts, from isolated syllables (many

nonsense syllables) to stressed syllables in disyllabic words. All training items are spoken by 30 talkers, to my awareness the largest number of talkers ever used in HVPT training. This degree of variability is intended to ensure that

learners will not repeatedly hear the same training token during a

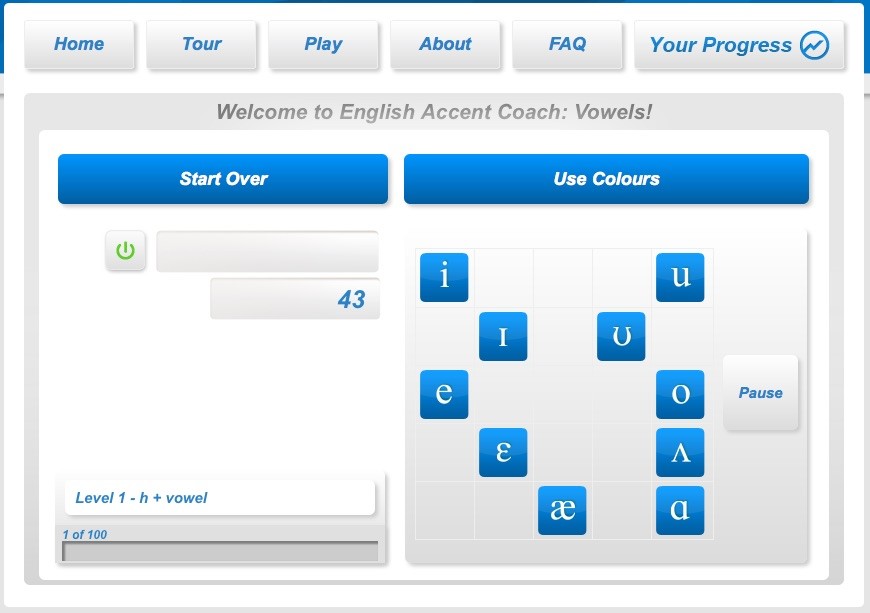

single training session. During a typical session, learners hear tokens

containing target vowels or consonants and must click on the phonetic

symbol for the sound that they believe they heard (see Figure 1). After

each click, the game provides immediate auditory and visual feedback on

the accuracy of the user’s selection. The vowel game also includes a

switch, which allows users to click on color key words instead of

phonetic symbols (e.g., green contains the sound /i/,blue contains /u/).

Figure 1. Screen shot of English Accent Coach vowel training application

Research Findings

Research using EAC and a precursor application (see Thomson,

2011) has been very promising. Apart from helping to determine if such

training is effective, this research has also shed light on how second

language pronunciation develops. For example, training learners to

perceive 10 English vowels in one phonetic context (i.e., following /b/

and /p/) was found to result in only limited transfer of learning to the

same ten vowels following other consonants. While the positive impact

of training on the perception of vowels in the training context is

encouraging, these early results demonstrated that second language

pronunciation may not develop sound-by-sound, but rather

context-by-context.

In a large-scale follow-up study over a 2-month period

(comprising approximately 10-12 hours of combined training over 40

sessions) 15 learners were trained to recognize 10 English vowels. For

the first nine sessions, vowels were presented in isolated /h + vowel/

syllables. For the next 29 sessions, the same vowels were presented

after other English consonants. Finally, training returned to the

original /h + vowel/ context for sessions 39 and 40. During the first

nine sessions with the /h + vowel/ context, the learners’ recognition of

English vowels improved session-by-session. However, despite 29

intervening training sessions in other contexts (10–38), when the /h +

vowel/ context was reintroduced during session 39, no further

improvement in vowel recognition was found to have occurred. This can be

attributed to the fact that from sessions 10-38, learners only ever

heard the 10 English vowels in other phonetic contexts. At the same

time, whenever any other phonetic context was repeated (e.g., vowels

after /b/, /d/, and /g/, during sessions 10 and 17), vowel recognition

scores in those contexts also improved.

In another study (Thomson & Derwing, 2016), my

colleague and I investigated whether EAC training that presents 10

vowels in nonsense syllables leads to greater improvement in the

pronunciation of 70 target words containing those vowels, relative to

training that primarily presents vowels in the 70 target words. To

answer this question, 31 learners were randomly assigned to either the

phonetically-oriented group, the word-oriented group, or a control

group. An elicited imitation task was used to record the learners’

productions of the 70 target words, before and after training (i.e.,

they heard the words in the sentence, The next word

is _____ and had to repeat the word in the sentence, Now I say ______). We found that the phonetically

oriented training group significantly improved in their pronunciation of

the 70 target words, while the word-focused group—trained to perceive

vowels using recordings of the 70 target words—did not.

Another interesting findingfrom EAC studies is that age does not appear to limit

learning. Learners as old as 60 years of age have participated in EAC

research with encouraging results. While older learners tend to have the

lowest scores at the outset, EAC facilitates rapid improvement. In

fact, the oldest learner in the 2011 Thomson study, a 50-year-old

female, demonstrated one of the greatest improvements.

Using EAC to Inform and Complement Traditional Classroom Instruction

Results of EAC studies (e.g., Thomson, 2011; Thomson & Derwing, 2016) can be used to inform classroom pronunciation

instruction. For example, instead of assuming that using the minimal

pair ship/sheep will result in the learning of these

contrastive vowel sounds in all word pairs, teachers likely need to

present many more pairs in order for learning to occur (e.g., hit/heat, sip/seep, fit/feet). Teachers should also be sure to

incorporate some practice of target sounds in nonsense syllables,

because this appears to lead to larger gains than training that contains

only real words.

EAC cannot replace the teacher, but it provides an important

complement to any course of pronunciation instruction. Learners can

create their own user accounts, which will allow them and their teachers

to track progress over time. In addition to a progress tool, learners

can also download and print report cards for individual sessions. This

functionality allows teachers to assign EAC activities as homework and

gives learners the ability to demonstrate that specific training

sessions have been completed.

References

Derwing, T. M., & Munro, M. J. (2015). Pronunciation fundamentals: evidence-based perspectives for L2

teaching and research. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing

Company.

Murphy, J. (2014). Myth 7: Teacher training programs provide

adequate preparation in how to teach pronunciation, In L. Grant, L.

(Ed.). Pronunciation myths: Applying second language research

to classroom teaching. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan

Press.

Thomson, R. I. (2011). Computer assisted pronunciation training: Targeting second language vowel perception improves pronunciation. CALICO Journal,

28, 744-765.

Isaacs, T. (2009). Integrating form and meaning in L2

pronunciation instruction. TESL Canada Journal, 27,

1-12.

Thomson, R. I., & Derwing, T. M. (2016). Is phonemic

training using nonsense or real words more effective? In J. Levis, H.

Le., I. Lucic, E. Simpson, & S. Vo (Eds.). Proceedings

of the 7th Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching

Conference. Oct. 2015. (pp. 88-97). Ames, IA: Iowa State

University.

Ron Thomson is associate professor of applied

linguistics at Brock University. His research focuses on the development

of second language pronunciation and oral fluency. |