By Christine Davidson Noon

Most kids love writing and illustrating their own books. The Center for the Advancement of Art-Based Literacy at the University of New Hampshire has a new spin on this, which is great for English language learners in multilevel or mainstreamed ESL classes. The center has developed workshops and DVDs in two instructional models, “Picturing Writing: Fostering Literacy Through Art” and “Image-Making Within The Writing Process.” These models develop creativity in students and greatly improve their reading and writing proficiency. What is unique about these art-based literacy models is that pictures, not words, initially drive the story. Students make pictures before they write.

Although I had read of the center’s impressive results in teaching English language learners’ reading and writing, I didn’t really understand the process until I took a workshop myself. Later, I had the director of the center and creator of the method, Beth Olshansky, present Picturing Writing and Image-Making to our state’s ESL teachers. Feedback was quite positive because instruction was both practical and creative, with scientifically-based research to support it. In New Hampshire, the implementation of the center’s methods resulted in dramatic improvement in literacy for our language learners who participated.

How It Works

The process begins with picture-making and then moves to oral language development, writing, and reading.

Creating the Art

In Image-Making, language learners create collage images from hand-painted papers they create. After students have a portfolio of papers, they cut out shapes and glue them to a painted background as a collage to develop each page of their story.

In Picturing Writing, the other model, students create crayon-resist images to develop their story ideas, using both watercolors and crayons for the books they will create.

Ruslan’s Picture Writing illustration of the Russian orphanage where he once lived.*

Though Image-Making and Picturing Writing are innovative methods, they are both structured interventions based on the tried and true Writing Process model. The methods incorporate visual and kinesthetic learning. Even non-English language speakers can participate on their first day of school by making pictures, which can “level the playing field.” Both methods incorporate the four language domains of listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

Oral Language

Oral language development begins with informal talking about what students know on any given topic in the curriculum or about their home country. For example, in a “Life Stories Project,” you can begin by telling a personal life story and then encouraging students to tell their own stories. For a child from the Dominican Republic or Mexico, the story might center on homesickness for a native country or family members left behind. For a child from a refugee camp, the story may include the excitement of having water that comes out of a faucet, rather than a watering hole a long walk from home.

Listening

As part of the listening domain, teachers should read strong, descriptive children’s literature, including poetry. Ask language learners who the characters are, what their triumphs and set backs are, and how the story ends. Students are encouraged to find books they love to read by themselves, in a group, or to another student, teacher, paraprofessional, or parent. Sometimes children are so new to the language they simply listen to the rhythm of English and look at the pictures.

Speaking

As they become less self-conscious, language learners are more comfortable speaking with others in their classrooms. They are so proud when they complete a book that they are scared but happy to read before an ESL or mainstream class.

Writing

Students create their own quality picture books from start to finish. Language learners start where they are comfortable and progress with the help of teachers and other kids. They are instructed to have a beginning, middle, and end, and to include a problem and a solution, which introduces them to the idea of literary conflict. Following the Writing Process model, students write, revise, and proofread their drafts, sometimes typing them on a classroom computer—another skill they learn or improve upon. If students are very new to the English language, they can dictate their stories to teachers who write down and read back the stories.

Reading

Language learners read their drafts and final revisions in pairs and groups. By the time their first book is completed, they are reading with more confidence. They continue to exchange ideas with peers and teachers, to make art, and to write. Teachers can have a special day when students receive their color photocopied books and stand before the class to read them. At the end of the day, they take the books home to share with family, and then after a week or two they bring them back to class to become part of the class library. Family members, no matter what their level of English language competency, can understand the books because they are composed of so many pictures.

As the literacy programs branch out to include reading for information, students find facts for their descriptions. They read illustrated reference books and find information on the Internet. Students come to see themselves as capable, improving their self-esteem and self-confidence. They begin to love reading. “That is really gratifying,” one teacher said after a school year of instruction in Image-Making.

Vocabulary Building

An important step in literacy through art is for language learners to increase and improve their vocabulary. This occurs during reading, but also when teaching the other three parts of the programs. Find a topic kids can relate to and then help them find which words “paint a picture”—the sun, the moon, mountains and rivers, favorite animals, their parents and siblings. To show the meaning of action words, you can display illustrations or scientific sketches, and even act out verbs: leap like a tiger, or hunch over like an old man shuffling down the street. Vivid vocabulary words and collations land on a group word wall and are then added to.

Language learners look at their own pictures for ideas and think of interesting words to describe them. After one of our teachers had implemented Picturing Writing for several weeks, she was amazed to find her students using a thesaurus. She had not introduced it; they had found it at the library. One of our students said “I love learning beautiful words.”

Integrating the Models With Curriculum

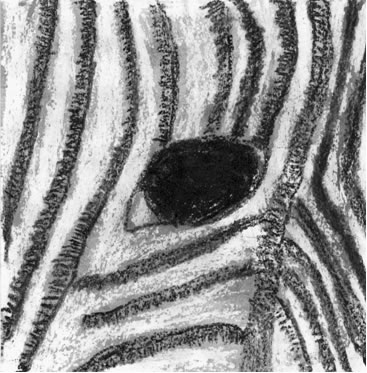

It is obvious that Picturing Writing and Image-Making would be easy to integrate into the curricula for history, art, and English. But they are also good for science. For example, as part of integrating physical science, language learners choose an animal to study and then write a “Who Am I?” trifold book. Students research the animals’ characteristics, creating artwork based on sketches, paintings, photographs, and scientific drawings. A Manchester student, Ange, created a fact-based poem illustrated with her paintings for her animal book, which she proudly read to the class:

I gallop across the grasslands.

I eat leaves and drink water.

I live in the Savannah of Africa.

I’m black and white.

I have stripes all over me.

Can you guess who I am?

Ange’s close-up of a zebra*

We found that the extensive vocabulary building and other verbal skills that students developed in order to create their beautifully crafted books positively affected their literacy skills. With the universal language of pictures placed at the core of thinking and writing, both of these models led to exceptional results for us.

Results

Beth Olshansky has traveled all over the United States and abroad to instruct teachers in her literacy program including Fowler, California, USA where 50% of students were English language learners and 75% were on free and reduced lunch. In September, 36% of third graders were reading below grade level and 34% were above grade level. After completing nine months of Picturing Writing instruction, only 3% of students scored below grade level and 75% scored above grade level. At Hallsville Elementary School in Manchester, New Hampshire, USA, where this literacy model was closely followed, the percent of Hallsville students scoring proficient and above increased by 30% to 73% over a 2-year period.

We’re used to writing being the last domain for English language learners to master. This is not the case when literacy is taught through art and oral language; students enthusiastically learn how to write as they tackle each new book project. Most English language learners in our state are mainstreamed and we discovered it was easy to incorporate the program in content area classrooms. Research conducted shows that the program is most effective when it is part of instruction for the entire school year or more.

More information on these methods, including instructional DVDs, is available from the Center for the Advancement of Art-Based Literacy at: www.picturingwriting.org

*please note that while copyright for this article belongs to TESOL International, copyright for the student work belongs to Beth Olshansky.

__________________________________

Christine Davidson Noon is the former director of the Title III English Language Acquisitions Program at the New Hampshire Department of Education. She has taught English composition and English as a second language and has 10 years’ experience as an education administrator. She is also a published writer of numerous articles and two books.