2015 TESOL Distinguished Researcher: Dr. Yasuko Kanno

by Cydny Black

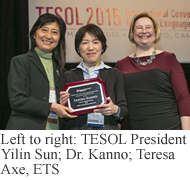

The title of Dr. Yasuko Kanno’s award-winning research, “‘I’m Not Going to Be, Like, for the AP’: English Language Learners’ Limited Access to Advanced College Preparatory Courses in High School,” almost has to be read aloud with a tinge of flair to be fully realized. And that’s exactly what Teresa Axe of ETS did at the 2015 TESOL International Convention & English Language Expo when she presented Kanno, a faculty member at Temple University, with the prestigious TESOL Award for Distinguished Research.

The title of Dr. Yasuko Kanno’s award-winning research, “‘I’m Not Going to Be, Like, for the AP’: English Language Learners’ Limited Access to Advanced College Preparatory Courses in High School,” almost has to be read aloud with a tinge of flair to be fully realized. And that’s exactly what Teresa Axe of ETS did at the 2015 TESOL International Convention & English Language Expo when she presented Kanno, a faculty member at Temple University, with the prestigious TESOL Award for Distinguished Research.

“So, what exactly does the title mean?” I naively asked when Kanno and I sat down to talk at the convention in Toronto this March. The explanation required some context. Kanno, in tandem with her doctoral student Sara Kangas, were interested in ELLs' college access. Quite surprisingly, Kanno explained, this is not a subject that has really been researched. Often when investigating issues of college access, researchers look at disparities between ethnic groups, household income levels, and socioeconomic backgrounds. There is a need to look at the ELLs’ experience uniquely to better understand the reasons they struggle to advance to college.

The study she performed followed a range of ELLs from high performing to low performing. What she found was that regardless of performance level, these students still experience limited access to advanced college-preparatory courses, which serve as a funnel into higher education. Her study illuminated structural barriers that exist for ELLs and contribute to a mentality that high-level education is not for them. That’s what the quote in the title was getting at. When asked about advanced placement (AP) courses, Erica, the high-performing student in the study, replied, “I’m not going to be, like, for the AP.” Kanno explains, as ELLs they don’t see themselves as as belonging to the caliber of students who take AP courses.

The study she performed followed a range of ELLs from high performing to low performing. What she found was that regardless of performance level, these students still experience limited access to advanced college-preparatory courses, which serve as a funnel into higher education. Her study illuminated structural barriers that exist for ELLs and contribute to a mentality that high-level education is not for them. That’s what the quote in the title was getting at. When asked about advanced placement (AP) courses, Erica, the high-performing student in the study, replied, “I’m not going to be, like, for the AP.” Kanno explains, as ELLs they don’t see themselves as as belonging to the caliber of students who take AP courses.

In ways, Kanno’s research is reflective of her own journey to self-empowerment within a foreign language context. As a promising high school student in Japan, Kanno was accepted into United World College of the Atlantic, a prestigious international school in the United Kingdom. It was there that she learned English. “It was a very sink-or-swim environment,” she expressed. “I myself internalized the deficit identity, the belief that there is something lacking in me because I didn’t speak English.” That experience got her thinking at an early age that there must be a better, more positive way to learn English.

After receiving her doctorate under the tutelage of Dr. Jim Cummins, Kanno worked at a university in Japan for 4 years but found that Japanese academia lacked real opportunities for women. After encountering years of discouraging rejections when she applied to institutions in North America, she got hired for a 1-year stint at Monterey Institute for International Studies, which blossomed into a position at the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle. It was at UW that while interviewing ELLs at the university level she was pushed to see what is going on with ELLs in high school.

When asked about future implications of her research, Kanno shared a story:

When I gave a talk at AAAL in March, one of the members of the audience said, “Isn't the same thing (ELLs’ limited access to advanced-level courses) happening to racial minority students, low-income students, and first-generation-college students?” While that is absolutely true, one crucial difference is that in the case of these other groups of students, we never institutionally condone their differential access to advanced courses—to do so would be discriminatory. Yet, in the case of ELLs, we somehow share a discourse that legitimizes policies that limit ELLs’ access to advanced courses. It is critical that we collectively interrogate the ideologies and discourses that normalize ELLs’ limited opportunity to learn.

Though Kanno insists that she is not a pioneer, saying, “I don’t think of myself as a trailblazer,” and then listing other scholars she finds more influential, her research has indeed launched a greater discussion about the achievement gap that exists for ELLs.

________________________________

Cydny Black is the program assistant for public policy and communications at TESOL International Association. In addition to her work for the association, Black is enrolled at American University, where she is working toward an MA in international communications. A DC transplant from her native Madison, Wisconsin, Black enjoys the outdoors, readings, and advocacy work.

TESOL Blogs

Interested in writing a blog for TESOL?

Contact

Tomiko Breland with your idea or for submission details.

Check out the latest TESOL Blogs, including our newest bloggers, writing on secondary education; adult education; teacher education; and speech, pronunciation, and listening:

|

Finding Common Ground in Multicultural Classrooms, by Nathan Hall

Think back to the first day of a new school year. It’s late summer, but you feel cold and uncomfortable. You don’t know the boy to your right or the girl behind you, or even the teacher. You start to think about how different you look from the rest of the students and spend so much time wondering what they think of you that you don’t form many opinions about them. And then the teacher says it’s time for everyone to introduce themselves. You may have experienced this with the added level of not having a common language—or least not one you spoke or understood well—with classmates who have different accents. Read More. Think back to the first day of a new school year. It’s late summer, but you feel cold and uncomfortable. You don’t know the boy to your right or the girl behind you, or even the teacher. You start to think about how different you look from the rest of the students and spend so much time wondering what they think of you that you don’t form many opinions about them. And then the teacher says it’s time for everyone to introduce themselves. You may have experienced this with the added level of not having a common language—or least not one you spoke or understood well—with classmates who have different accents. Read More.

|

|

Options in Classroom Self-Assessment, by Robert Sheppard

I’ll be honest: It took me a while to come around to the notion of self-assessment. All I could picture was my sneeringly too-cool high-school self giving my apathetically underachieving high school self A+ after unearned A+. I’ll be honest: It took me a while to come around to the notion of self-assessment. All I could picture was my sneeringly too-cool high-school self giving my apathetically underachieving high school self A+ after unearned A+.

Can we really trust students to assess themselves? Is a student’s assessment of her own progress or performance reliable? Is it valid? If reliability and validity aren’t guaranteed, then what’s the point? These are important questions to ask, but as long as we think of assessment not just as a tool for bureaucracy and accountability but as an opportunity to empower our learners, and as long as we keep an eye to its limits and its role in a broader assessment system, then such self-assessment is most certainly a worthy undertaking. Read More. |

|

Reading Challenges for ELs in the Age of the Common Core, by Judie Haynes

Learning to read in English presents many challenges for English learners (ELs) in the K–12 classroom, especially true in this age of high stakes standardized testing based on the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). ELs face many obstacles when reading in English. Most literature taught in K–12 is culture bound. Teachers expect all students to have prior knowledge of literary genres such as fairy tales, myths, legends, and tall tales. If the teacher has not built background information, ELs who have learned phonics may be able to read the words, but that doesn’t mean they will understand the text. Read More. Learning to read in English presents many challenges for English learners (ELs) in the K–12 classroom, especially true in this age of high stakes standardized testing based on the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). ELs face many obstacles when reading in English. Most literature taught in K–12 is culture bound. Teachers expect all students to have prior knowledge of literary genres such as fairy tales, myths, legends, and tall tales. If the teacher has not built background information, ELs who have learned phonics may be able to read the words, but that doesn’t mean they will understand the text. Read More.

|

|

Blogging for Learning in TESOL Teacher Ed, by Kristen Lindahl

Storytelling is one of the most powerful human language acts, and now it may be one way to help TESOL teachers process and retain information. We know that teachers’ life experiences and beliefs are some of the biggest contributors to their practices (see Johnson, 2009), but creating time for teachers to verbalize these experiences and beliefs, let alone acknowledge and reflect upon them, can be challenging for teacher educators. Teaching English worldwide in all its dimensions—political, social, economic, theoretical—may cause beliefs to surface and influence teacher decisions, some of which they may not even be aware. Read More. Storytelling is one of the most powerful human language acts, and now it may be one way to help TESOL teachers process and retain information. We know that teachers’ life experiences and beliefs are some of the biggest contributors to their practices (see Johnson, 2009), but creating time for teachers to verbalize these experiences and beliefs, let alone acknowledge and reflect upon them, can be challenging for teacher educators. Teaching English worldwide in all its dimensions—political, social, economic, theoretical—may cause beliefs to surface and influence teacher decisions, some of which they may not even be aware. Read More.

|