Designing a Vocabulary Approach: 4 Research-Based Practices

by Frances A. Boyd

Students and textbooks may change from term to term, but the challenge of vocabulary learning remains. As professionals, we want to be up-to-date. As practical teachers, we need to keep things simple. As teachers of academic English learners, we know the size and scope of the vocabulary-learning task is far greater than the class time allotted to it. What many of us could use is a manageable, research-based, and collaborative approach. These four practices, applicable to any mature learners, organize and prioritize a teacher’s activity. They assume that students can and will share the burden and joy of vocabulary selection and study. So, let’s get started.

Students and textbooks may change from term to term, but the challenge of vocabulary learning remains. As professionals, we want to be up-to-date. As practical teachers, we need to keep things simple. As teachers of academic English learners, we know the size and scope of the vocabulary-learning task is far greater than the class time allotted to it. What many of us could use is a manageable, research-based, and collaborative approach. These four practices, applicable to any mature learners, organize and prioritize a teacher’s activity. They assume that students can and will share the burden and joy of vocabulary selection and study. So, let’s get started.

Practice #1: Focus on Target Words and Phrases

Selecting Vocabulary

To begin, teachers need to carefully select vocabulary from content-based course materials—target words and phrases—and practice these items with intentional frequency.

Careful selection of vocabulary is essential. Too often, textbooks underestimate the frequency of multiword units, highlighting mostly single words. Yet, studies in corpus linguistics reveal that two-word verbs, delexicalized verbs (do, get, give, have, keep, look, make, put, take), lexical phrases (fixed concepts), idioms, and common collocation patterns are “ubiquitous, pervasive, and astoundingly frequent” in English (Hinkel, 2019). Moreover, textbooks cannot customize vocabulary choices for your learners, taking into account what they know, might need to know, or are interested in.

Thus, the first practice suggests that you begin by analyzing the vocabulary of each textbook unit and then modify the list by combing through source texts and exercises with expanded criteria in mind.

Thus, the first practice suggests that you begin by analyzing the vocabulary of each textbook unit and then modify the list by combing through source texts and exercises with expanded criteria in mind.

Implementing Spaced Repetition

Once selected, the target words and phrases should become the focus of spaced repetition practice. According to the forgetting curve, new information is not retained unless repeated in ever-lengthening time periods. To learn a word is a process that moves from noticing to retrieving from memory to eventually using the word. This implies that, to support long-term memory, students need frequent, short, retrieval activities (Nation, 2013).

For such spaced repetition, it is helpful to try those activities that take little preparation for teachers but a great deal of critical thinking by students. Various sorting activities fit the bill. For example: Students can sort a list of 20–25 vocabulary items by knowledge, writing each under the headings of “known, unknown, partially known.” Or, on another day: Pairs can sort that same list by syllable stress, writing each word or multiword item (considered as a wordlike unit) under the headings of “1st-syllable stress,” and so on. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Students sort vocabulary by syllable stress.

In sum, to build vocabulary, you should select a rich range of single- and multiword units, then engage students in frequent practice of these target words and phrases. Occasionally, too, you also need to take time for longer activities that promote creative use of new vocabulary.

Practice #2: Teach Strategies

To gain proficiency, students must grow increasingly independent as vocabulary learners. For this, they need strategies, especially to confront unknown vocabulary and to record and review it.

Lexical Inferencing

The most valuable strategy—bar none—is lexical inferencing. This refers to the ability to look around and inside of words in order to guess their meaning. By developing this skill, students build reading fluency and vocabulary retention.

Using Context: To be able to look around a word and guess its meaning from its use in a sentence, students must know 95–98% of the context. This means that the texts for comprehension are at or slightly below the students’ comprehension level. Or, more routinely, teachers or textbooks can isolate new vocabulary in pedagogical sentences that are salted with clues.

Using Word Parts: To be able to look inside a word and guess its meaning from word parts is more difficult and can be misleading. Still, on the whole, it is worthwhile to familiarize students with the concept of word parts as well as the most common prefixes, stems, and suffixes.

Systems for Recording and Reviewing

A second very valuable strategy is to have systems to record and review new vocabulary. All students need concrete techniques, and most need repeated reminders to use them. Analog devices such as vocabulary notebooks and word cards are backed by decades of research. However, our 21st-century students, often comfortable in the frictionless digital environment, may balk at the physical effort and time it takes to write down notes and carry around paper. Yet, it is precisely this kind of “desirable difficulty” that leads to longer-term learning (Bjork, 2017).

In short, just as important as teaching target words is giving students specific tools to deal with unfamiliar vocabulary they encounter.

Practice #3: Create Teachable Moments

Whatever the focus of a lesson, it is useful to create opportunities for informal but explicit mini-lessons in vocabulary. In this way, seemingly spontaneous but cleverly planned teaching can nurture natural curiosity and enjoyment. Among many techniques are these two: answering vocabulary questions with questions and responding to student situations with new vocabulary.

Answer Questions With Questions

When a student asks for a definition, you can answer with questions that elicit and organize word knowledge. To “know” a word is not merely to be an acquaintance but a close friend: to be aware of its word forms, meanings, and usage. Imagine this scenario:

Student: What does conspicuous mean?

Teacher: (elicits and writes)

Meaning = easily seen

Word forms = noun…verb…adjective…adverb

Usage = a … sign; …consumption (lexical phrase)

Use New Vocabulary

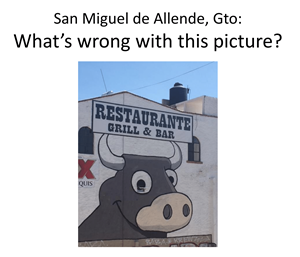

Another way to create teachable moments for vocabulary is to respond to student situations with new words and phrases: idioms, phrasal verbs, lexical phrases, and so on (see Figure 2). When a recently absent student returns to class, you might ask: “Have you been under the weather?” Or, when a student has been unusually quiet, you might invite him or her to speak: “Would you like to chime in?” To jog the memory, it might be a good idea to keep handy a list of such situations and matching vocabulary.

In sum, it is often possible to use students’ questions and common situations to build awareness, enjoyment, and lexicon. Words, after all, are the building blocks of communication. Students can always use more of them and can always use more information about the ones they “know.”

Figure 2. Example image for teaching a lexical phrase.

Practice #4: Activate Collaborative Reading

Extensive reading—reading many, enjoyable, easy books—is one of the most effective yet least utilized practices for expanding vocabulary. Collaborative activities, such as book groups, can eliminate some of the drawbacks and encourage reluctant readers, sustain interest, and multiply the benefits.

The habit of reading, a major academic and life skill, has long been identified as a significant means of both reinforcing known vocabulary and encountering new vocabulary (Bamford & Day, 1998). When we read, the brain is immersed in constructing meaning from language on the page; vocabulary is embedded in context and in content.

Book Groups

Book groups, in which learners read alone but discuss together, rely on rotating roles and collaboration to engage students. Over several weeks, the members of each small group read the same book. In weekly meetings, they report on and discuss their book, according to rotating roles (e.g., a discussion leader, conflict analyzer, and vocabulary expert). Occasionally, they report to other groups, who are reading different books.

For book group material, it is essential that the language level be at or slightly below the learners’ comprehension; otherwise, the project becomes burdensome. For lower levels (A1–B1), you can choose from a rich language-learner literature, including published books by Oxford (Oxford Book Worms) and Pearson (Pearson Readers), and

free online graded readers offered by Paul Nation; for higher levels (B2–C2), there is a wide array of young adult (YA) and adult choices.

News Groups

News groups, in which a similar pedagogy is utilized with news articles, can vary the reading diet. If following an issue from week to week, students will find that the vocabulary begins to repeat (Boyd, 2018).

In short, mastery of vocabulary requires that the learner notice—or decontextualize—words and phrases, as well as retrieve—or recontextualize—them. By setting up collaborative book and/or news groups, you create fertile ground for students to practice their word-learning strategies, make student-selected choices, and enjoy reading, which is certainly one of the best ways to learn vocabulary.

Conclusion

For many years a backwater, vocabulary is now in the forefront of research on the learner and the lexicon. Teachers can apply these research-based insights by designing a comprehensive approach out of four practices, practices which can be understood as flexible principles. A simple pneumonic makes them memorable—it’s a FACT:

Focus on target words and phrases

Activate collaborative reading

Create teachable moments

Teach strategies

What also makes learning memorable is sharing your inner “word nerd.” What new word or phrase have you learned? What new research are you thinking about? Teachers who share their enthusiasm for the language and the learning of it also share a deep truth about English: It is a dynamic, fluid, and mutable language. English is a river, goes the old metaphor. With a set of clear practices, we have a better chance of helping students stay afloat on it and enjoy the ride.

References

Bamford, J., & Day, R. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Bjork, R. A. (2017). Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. In I. Wallace & L. Kirkman (Eds.), Best of the best: Progress (pp. 81–85). Carmarthen, Wales: Crown House.

Boyd, F. A. (2018). News groups. In J. Vorholt (Ed.), New ways in teaching speaking (2nd ed., pp. 43–44). Alexandria VA: TESOL Press.

Hinkel, E. (Ed.). (2019). Teaching essential units of language: Beyond single-word vocabulary. New York, NY: Routledge.

Nation, I. S. P. (2013). Learning vocabulary in another language (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Dr. Frances Boyd has been teaching students and developing teachers for more than 35 years in the United States and abroad, in China, Columbia, Kyrgyzstan, and Mexico. She serves on the faculty of Columbia University’s American Language Program in the School of Professional Studies. Coeditor of the academic book series NorthStar, now in its fifth edition (Pearson), she is also a frequent featured speaker at international ELT conferences. Boyd holds a BA from Oberlin College, an MA from the University of Wisconsin, and an EdD from Teachers College, Columbia University.