Unlocking Complex Grammar: 4 Steps for Reading and Writing

by Heather Weger and Julie Lake

In our English for Law Purposes context, we have noticed

that students in our writing classes often struggle to understand and produce

texts because of gaps in their grammatical awareness. This gap may explain why

learners tend to make “safe choices” (Neumann, 2014) when writing. These

choices, however, can disadvantage students in contexts where writing is a

primary measure of success, as is true of many advanced academic programs

(Swales & Feak, 2012) and professional programs like ours (e.g., Baffy

& Schaetzel, 2019). This article outlines four steps to increase

students’ grammatical accuracy by analyzing grammar in reading and applying

this analysis to student writing.

In our English for Law Purposes context, we have noticed

that students in our writing classes often struggle to understand and produce

texts because of gaps in their grammatical awareness. This gap may explain why

learners tend to make “safe choices” (Neumann, 2014) when writing. These

choices, however, can disadvantage students in contexts where writing is a

primary measure of success, as is true of many advanced academic programs

(Swales & Feak, 2012) and professional programs like ours (e.g., Baffy

& Schaetzel, 2019). This article outlines four steps to increase

students’ grammatical accuracy by analyzing grammar in reading and applying

this analysis to student writing.

As detailed

in this article, our approach evolved into a four-step process that moves from

scaffolded, contextualized grammar analysis to students’ independently

recognizing and correcting errors in their own writing. We drew inspiration

from Grabe (2014), which shows a clear link between decoding complex lexico-grammatical

structures and reading ability, especially for advanced-level authentic texts.

We hope that you can use these strategies in your teaching context to encourage

your students to better understand and use complex grammar.

Step 1: Analysis of

Complex Structures in Authentic Texts

In Step 1,

the cornerstone step, we ask learners to analyze complex, challenging grammar

structures in authentic readings. A foundational activity is a close-reading

strategy that helps students grasp not only the main ideas but the details of a

text.

Though

reading for main ideas, and not details, is often an effective reading

strategy, skilled readers in advanced-degree programs and specialized fields

often need to focus on these very details. A close-reading strategy can help

learners grasp these details and, ultimately, clarify the meaning of an

important text by developing learners’ linguistic knowledge. For example, the

use of crucial in the following excerpt, taken from a

scholarly legal article on the issue of gun laws and gun rights in the United

States, signals to the reader that this excerpt contains an important detail

the reader should attend to:

There is a

crucial divide in these laws between those that issue permits essentially

automatically to anyone who applies and those that employ a measure of

discretion. The majority of states fall into the former category, often called

“shall issue,” giving states and municipalities no choice but to issue a permit

so long as the person is not a felon, a domestic violence offender, or

seriously mentally ill. (Meltzer, 2014, p. 1498)

Using this

excerpt, we coach our students through a close-reading strategy. Though we do

not have space to show the entire process, Figures 1, 2, and 3 show selected

materials to demonstrate the substeps. For each substep, we first let students

try close reading individually or in small groups before showing our analysis.

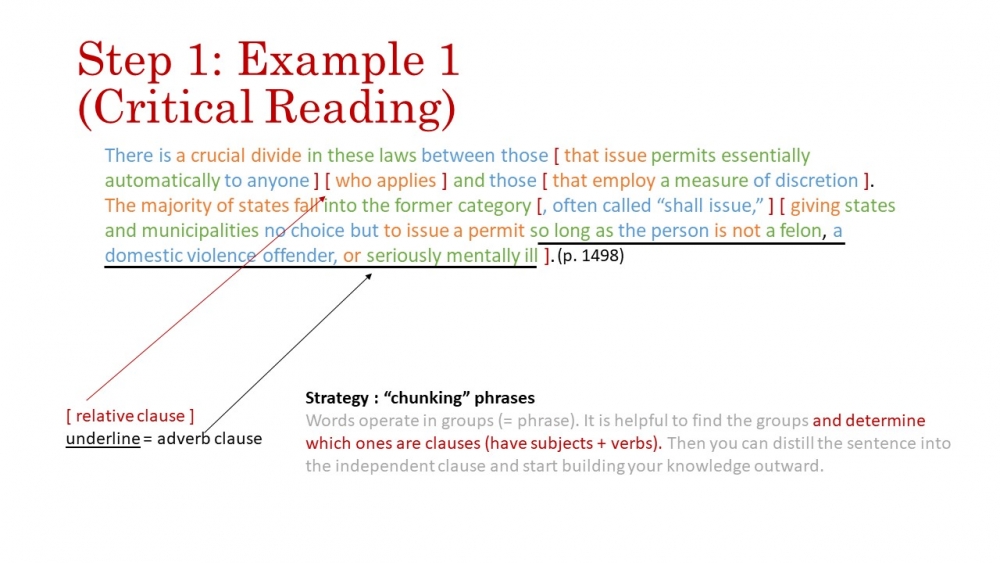

Substep

1

Students find

the groups of words (or chunks). We generally have students

chunk at the phrase level, but students can group words in a variety of

meaningful ways. Figure 1 shows our use of different colors for different

phrases; please note that these colors are arbitrary and do not signify

systematic differences in grammar structures.

Substep

2

Students determine the clauses. Using animation, we

demonstrate our coding system to indicate the relative clauses and adverb

clauses (see the use of brackets and underlining in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Example of finding groups of words and

determining clauses. (

Click here to enlarge)

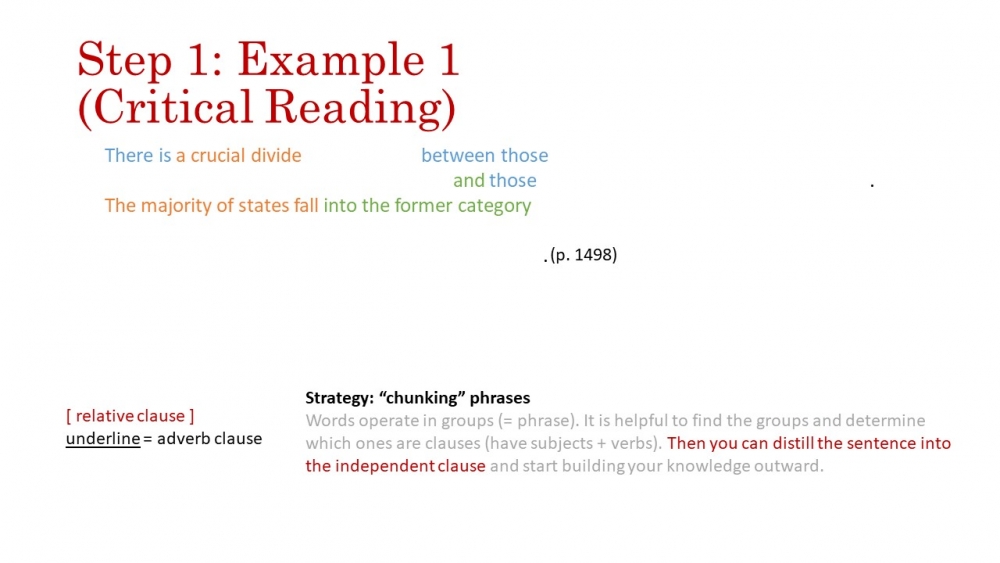

Substep

3

Students focus on the independent

clauses. We accomplish this by “hiding” all the dependent

clauses so that students “see” only the independent clauses (see Figure 2). By

doing this, students can locate the main ideas of the sentences. In the first

sentence, the independent clause There is a crucial divide between [A

and B] shows that there are two categories. In the second sentence,

the independent clause The majority of states fall into the former

category shows that most states are in category A.

Figure 2.

Example of focusing on independent clauses. (

Click here to enlarge)

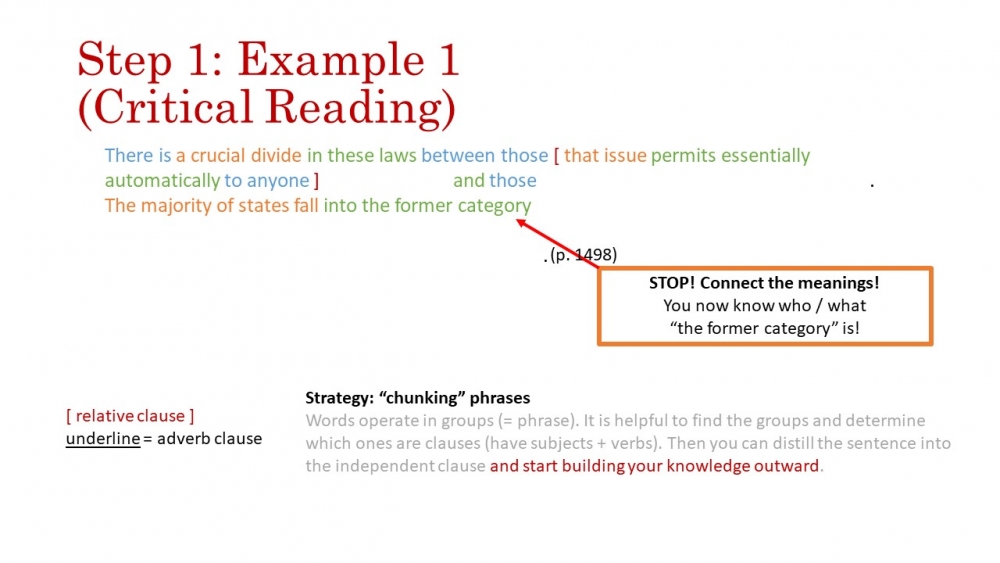

Substep

4

Students build up

knowledge by adding the “hidden” chunks back in one by one.

Students can now focus on understanding important details. As one example of an

“aha” moment, see Figure 3, which shows how adding in chunks of information

affects our understanding of the text. When we add back in the first relative

clause, we prompt the students to connect the meanings across the two

sentences. This relative clause provides the detailed information: what is true

of the majority of states.

Figure 3. Example of building up

knowledge. (

Click here to enlarge)

In summary,

this first step (composed of four substeps) is foundational. It helps learners

understand the complex grammar that creates meaning in authentic texts, which

is a tool for discovering errors in their writing.

Step 2: Analysis and/or

Correction of Teacher-Selected Errors

In Step 2,

we select problem sentences from student texts or authentic texts with complex

error types and guide students through an analysis in which they detect and

correct these errors. Rather than focus on specific activities, this article

outlines options for texts, activities, conditions, and type of feedback based

on our specific context of English for Law Purposes (see Table 1).

By creating

different combinations, students can start to build up their confidence to

detect and, ultimately, correct grammar errors. For example, you could create a

controlled practice activity using an authentic legal memo that has

subject-verb agreement errors inserted. Without any explicit feedback, students

could then work in small groups to locate the subject-verb agreement errors and

fix them.

Table

1.Options for and Examples of Texts, Activities, Conditions, and Types of

Feedback

|

What texts can you mine for

errors? |

• Authentic texts:

cases, law review articles, appellate decisions, legal memos

• Student-generated texts: case briefs, exams, timed writings,

scholarly papers |

|

What activities can you use? |

• Guided instruction: Provide texts with errors

highlighted or indicated in some way. Model for students how to find and fix

errors.

• Focused practice: Provide a list of

decontextualized, discrete errors of one type (e.g., article usage). Have

students fix errors.

• Independent practice: Students use proofreading

skills to identify and correct errors in authentic and/or student texts without

any highlighting/clues. |

|

What

conditions can you present these activities

in? |

• In class: demonstration in front of group or small

groups

• In office hours: individual or small group

conferences

• At home: homework |

|

What type of feedback can you

provide? |

• Highlight

error.

• Provide

metalinguistic feedback.

• Explicitly

correct error. |

In summary,

this second step helps learners better understand and discover errors in

complex texts, including authentic and student-generated writing. Though Step 2

has students analyze and correct teacher-selected errors, Step 3 pushes

students toward recognizing errors in their own writing.

Step 3: Analysis and/or

Correction of Student-Selected Errors

The third

step repeats many of the previous activities with students—rather than

teachers—selecting the texts for analysis (see Step 1) or errors in

student-generated texts (see Step 2). In other words, we remove the

scaffolding, allowing students to take more ownership of their language

development. Students can work individually or in reading/writing pods for this

step, receiving feedback either from their peers or from you. Your feedback

leads to the final step, the creation of an accuracy log.

Step 4: The Accuracy

Log

The final

step uses an activity we call the accuracy log (AL) to help learners recognize

patterns of errors they have when writing, whether word-level or clause-level.

We explain the AL to students as a tool to help them track their frequently

occurring error-types so that they can develop strategies to avoid and/or correct

these errors.

The AL has

four columns that correspond to four features (see Table 2). The first feature

is the student’s original sentence with one or more errors. The second feature

is a corrected sentence. The third feature is an explanation of the type of

error(s). The final feature, frequency, indicates how many times a given error

occurs in a particular piece of writing; we use this feature because our goal

is not to track every single error, but to use the AL as a way for students to recognize

the types of errors that they frequently make.

Table 2.

Sample Accuracy Log

|

Original Sentence* (With

Error) |

Corrected

Sentence |

Analysis/Explanation (in your own words and/or using

grammatical terms) |

Frequency of Error (i.e., how many times did you

make this error) |

|

Plaintiff (Lewis)

lived in an apartment building that owned by one

of the defendants. |

Two possible

corrections

1. Plaintiff

(Lewis) lived in an apartment building that was

owned by one of the defendants.

2. Plaintiff

(Lewis) lived in an apartment building owned by

one of the defendants. |

The error occurs

in a relative clause that needs a passive voice verb.

1. Passive

voice correction (insert the missing be verb for the

relative clause)

2. Reduced

relative clause correction (omit the relative pronoun) |

I made this error

2 times. |

*The

original sentence is adapted from Baffy and Schaetzel (2019, p. 234).

Students

tend to struggle most with the analysis (or explanation) of what caused the

error (the third feature in Table 2) because it can be difficult to articulate

why an error has occurred. However, this feature is critical to the AL because

it helps learners move from thinking of error correction as simply responding

to a command from the teacher (The teacher told me to add an –s

here) and toward recognizing—and correcting—the error autonomously

(I see that I need to make this word plural, and that means I need to

add an –s).

Through a

scaffolded process, we guide learners toward this self-analysis of recognizing

and correcting their errors using the AL. We start by using a teacher-created

model containing errors. Students work in groups to proofread for errors,

discuss errors they discover, and jointly create an AL. Second, students create

their own AL using several samples of their own writing, which allows them to

look for frequently occurring patterns rather than focusing on fixing all the

errors in one document and making that one document perfect. Third, students

receive an unmarked sample of their writing from the same genre. Students can

either correct the unmarked sample by looking for error types already

identified in their AL or record additional error types in their AL.

The final

step in this scaffolded process is meeting with students to discuss their AL.

Often, we find that our conversations focus on that third column, the

explanation of the error type, and, more importantly, why learners are making

those errors. In short, this cycle helps students better understand where they

are in their language development. They move from responding to a simple

command to thinking about how they have approached the sentence and how that

approach has led them to make a particular error type.

Conclusion

We hope that

these four steps help you think of ways to guide your learners into decoding

complex grammar, using that decoding skill to improve reading comprehension,

and detecting (and correcting) errors in their own writing. We have found that

our students have become more confident and independent writers through this

process.

References

Baffy, M., & Schaetzel, K. (2019). Academic legal discourse and analysis: Essential skills for

international students studying law in the United States. Wolters

Kluwer.

Grabe, W.

(2014). Key issues in L2 reading development. In X. Deng & R. Seow

(Eds.), CELC Symposium bridging research and pedagogy (pp.

8–18). Centre for English Language Communication.

Meltzer, J.

(2014). Open carry for all: Heller and our nineteenth-century second amendment. Yale LJ, 123, 1486–1530.

Neumann, H.

(2014). Teacher assessment of grammatical ability in second language academic

writing: A case study. Journal of Second Language Writing, 24, 83–107.

Swales, J.,

& Feak, C. (2012). Academic writing for graduate

students (3rd ed.). The University of Michigan Press.

Heather

Weger is a lecturer of Legal English at

Georgetown University Law Center where she designs and delivers curriculum for

multilingual students pursuing a Master of Law (LLM) degree. She also serves as

a coeditor for the TESOL Applied Linguistics Interest Section newsletter, AL

Forum.

Julie Lake

is a lecturer of Legal English at Georgetown University Law Center. She relies

on her background in linguistics and language-education pedagogy to help

multilingual law students navigate the linguistic demands of law school. She is

also on the leadership team for TESOL’s Career Path Development Professional

Learning Network.