Translanguaging in Bilingual and ESL Classrooms

by Ann Ebe, Mary Soto, Yvonne Freeman, and David Freeman

There is evidence of translanguaging all around us in every

part of the world. Delicatessens advertise delicacies on signs in several

languages, governments post announcements in languages most often spoken by

citizens, and advertisers draw on the languages of their potential customers.

Translanguaging is the typical way bilinguals use language as they communicate

in their communities. García (2009) defines translanguaging as the “multiple

discursive practices in which bilinguals engage in order to make sense of their

bilingual worlds” (p. 45).

There is evidence of translanguaging all around us in every

part of the world. Delicatessens advertise delicacies on signs in several

languages, governments post announcements in languages most often spoken by

citizens, and advertisers draw on the languages of their potential customers.

Translanguaging is the typical way bilinguals use language as they communicate

in their communities. García (2009) defines translanguaging as the “multiple

discursive practices in which bilinguals engage in order to make sense of their

bilingual worlds” (p. 45).

What

Is Translanguaging?

Translanguaging

Although

bilinguals naturally use all the languages they have acquired outside school,

in many schools they are limited to using just one language. Even in bilingual

programs, bilinguals often are required to use only the target language when

studying different subjects. Cummins (2007) argues that this strict separation

of languages, which he terms “the two solitudes,” stems from a misconception

that hinders both language acquisition and academic content development.

As García

(2017) and others have explained, bilinguals have one complex linguistic system

that has features of two or more languages that they refer to as a linguistic

repertoire (García, Ibarra Johnson, & Seltzer, 2017). Students in

bilingual and English as a second language (ESL) classrooms draw on their

linguistic repertoires to communicate and to make sense of instruction.

Teachers who incorporate translanguaging using all their students’ language

resources support the acquisition of both language and content.

Concurrent

Translation

Strategic

use of translanguaging supports learning, but translanguaging is not concurrent

translation. In concurrent translation, the teacher translates instruction into

students’ home languages, an ineffective approach to teaching language. If

teachers constantly translate, students only attend to the language that is

easiest for them to understand. In contrast, translanguaging is the strategic

use of the students’ home languages to help them understand instruction and

acquire a new language.

Strategic

use of translanguaging supports learning, but translanguaging is not concurrent

translation. In concurrent translation, the teacher translates instruction into

students’ home languages, an ineffective approach to teaching language. If

teachers constantly translate, students only attend to the language that is

easiest for them to understand. In contrast, translanguaging is the strategic

use of the students’ home languages to help them understand instruction and

acquire a new language.

Code-Switching

Code-switching

is a term that has been used to describe the use of two or more languages. This

term is based on the idea that bilinguals have separate languages (or codes)

and switch from one to another. In contrast, translanguaging views bilinguals

as having one complex language system, and bilinguals draw on the features

(phonemes, morphemes, syntactic structures, etc.) of all their languages as

they communicate. Baker and Wright (2017) point out that “children [and adults]

pragmatically use both their languages in order to maximize understanding and

performance in any lesson” (p. 280). This use extends to adulthood as well.

Purposes of Translanguaging

When

teachers use translanguaging strategically in ESL contexts, they allow their

students to draw on the full range of their language resources to acquire

English and develop academic content. In bilingual contexts, teachers affirm

students’ bilingual identities, build metalinguistic understanding by comparing

languages, and scaffold instruction by strategically drawing on students’ home

languages while still systematically allocating a major portion of

instructional time for each of the languages of instruction. In the following

sections, we provide specific examples of using translanguaging

strategies.

Translanguaging Examples

Using Translanguaging

in the Classroom or Remotely

In an ESL or

bilingual classroom, a teacher reads a story aloud to the class in English.

Throughout the reading, the teacher has selected parts of the text for students

to talk about with a partner. When the time comes for students to “turn and

talk,” they are invited to share their thoughts in their home language or

English with their paired same-home-language partner. Depending on the

classroom context, students can then share back with the whole group in English

or bilingually.

During

remote learning, students could be invited to respond to the whole group in

either their home language or in English, be put into virtual rooms to talk

about the story with same-language partners, or write a response in the home

language or English. Teachers who do not speak their students’ home languages

can use Google Translate or other students to get the gist.

Whether

learning in the classroom or virtually, there are opportunities to use

students’ language resources to involve families. Students can retell and

discuss a story with a family member in the home language. Cynthia, a teacher

in New York City, read the bilingual book My

Diary from Here to There by Amada Irma Pérez (2002) about

a girl keeping a diary as her family travels from Mexico to their new home in

the United States. The teacher invited her immigrant students to write a diary

entry about their own journey to their new country or interview relatives. The

entry could be in English, the home language, or a combination.

Translanguaging as a

Literary Device

Many authors

use translanguaging as a literary device. Translanguaging in a text can make it

more authentic and culturally relevant for students. Texts with translanguaging

can be used as a model for student writing. For example, an eighth-grade

English language arts teacher had her multilingual students write New Year’s

poems following the model of the New Year’s poem in the novel Inside

Out and Back Again by Thanhhà Lại (2013). In the story,

the author describes New Year in Vietnam using English and Vietnamese. The

students wrote poems describing their own country’s New Year’s traditions using

their home languages and English as a literary device in their poems.

Translanguaging in

Science

Translanguaging can be planned in all

subject areas to meet standards. Typically, standards can be met in any

language. For example, during science time in one first-grade class, students

read about and discussed plant growth in home language groups. They measured

the plants they were growing and then recorded their findings in their plant

growth journal in their home languages. They then discussed the findings in

English and in their home languages in same-language groups.

They met the

science standards because the standards did not specify that students were to

“gather information using simple equipment such as non-standard measurement

tools” and “communicate findings about simple investigations” in

English. Translanguaging opportunities can be made available to

students to meet learning standards wherever there are multilingual students,

regardless of whether teachers are bilingual or speak their students’ home

languages.

Using Translanguaging

to Meet Language Arts Standards

When

teaching English language arts to emergent bilinguals, teachers must meet

rigorous standards and are often asked to do this using mandated curriculum

designed for native English speakers. In order to provide equitable access to

their students, teachers can create units of study that incorporate engaging

activities and translanguaging into their language arts curriculum (Soto,

Freeman, & Freeman, 2020).

As a final

example of using translanguaging strategies, we describe how teachers can meet

the challenge of teaching grade-level content in a unit focused on a topic that

is often covered in the upper elementary grades: natural disasters.

In order to

make any unit topic more engaging, teachers can help to promote inquiry by

coming up with big questions to explore throughout the unit. Big questions for

investigation in a Natural Disasters unit might be “What are the causes of

natural disasters? or “How do people respond to natural disasters?”

To scaffold

the content of inquiry-based units, teachers provide access for ESL and

bilingual students by using translanguaging with a preview/view/review

design:

-

Preview:

Students first engage in preview activities in the home language or English

that help them build background and key vocabulary.

-

View:

Students participate in carefully scaffolded lessons in the target language.

-

Review:

Review activities are designed to show what students have learned throughout

the unit and can be done bilingually.

In the

Natural Disasters unit, students begin the preview by working in same-language

groups, looking at photos of several different types of natural disasters. In

their groups they discuss questions, such as “Which are the most dangerous?”

and “Why are they so dangerous?”

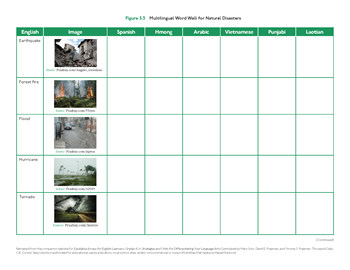

Once

students discuss in groups, the teacher can lead students in completing a KW

chart: What do we know about natural disasters? What do we want to know? In

addition, the teacher can work with the students to create a bilingual or

multilingual wall chart with an image of a natural disaster in the first

column, the word in English in the second column, and the word in the students’

home languages in the third column (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Multilingual word wall for natural

disasters. (Click here to enlarge.) From the companion website for Equitable Access for

English Learners, Grades K-6: Strategies and Units for Differentiating Your

Language Arts Curriculum, by M. Soto, D. E. Freeman, and Y. S.

Freeman, 2020. Copyright 2020 by Corwin. https://resources.corwin.com/equitableaccessk6/student-resources/chapter-5

During the

view portion of the unit, students read a variety of historical fiction and

fiction stories, such as the I

Survived series by Tarshis and Dawson, as well as texts from the

language arts textbook. As they read, the teacher provides a graphic organizer

where students can summarize main events and make predictions about whether the

events and characters are fact or fiction. These graphic organizers can be

completed in the student’s home language or in English. After reading, students

can do research to find out if their predictions were correct.

At the end

of the unit, as a review activity, students can pick a natural disaster that

they find especially interesting and do research about the specifics of that

event. They can use the information they gather to create their own historical

fiction story. In order to incorporate translanguaging, students can be

encouraged to do research and brainstorm ideas in their home language and in

English. They can also work in same-language groups to write and edit their

stories. Then, they can type up their stories and share them with classmates.

Using the preview/engage/review approach enables teachers to make mandated

English language arts content accessible to our emergent bilingual

students.

Translanguaging in the Classroom

Translanguaging

is a term to describe the language practices of emergent bilinguals. These

students have a single linguistic repertoire with features of two or more named

languages, such as English and Spanish or Mandarin. When teachers use translanguaging

strategies, such as the ones we have described in this article, in a planned

and strategic way, they draw on all the language resources their students bring

to the classroom. The strategic use of translanguaging promotes students’

bilingual identities and helps them develop both academic language and academic

content knowledge.

References

Baker, C.,

& Wright, W. (2017). Foundations of bilingual education and

bilingualism (6th ed.). Multilingual Matters.

Cummins, J.

(2007). Rethinking monolingual instructional strategies in multilingual

classrooms. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics,

10(2), 221–240.

García, O.

(2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global

perspective. Wiley-Blackwell.

García, O.,

Ibarra Johnson, S., & Seltzer, K. (2017). The translanguaging

classroom: Leveraging student bilingualism for learning. Caslon.

Soto, M.,

Freeman, D. E., & Freeman, Y. S. (2020). Equitable access for

English learners: Strategies and units for differentiating your language arts

curriculum. Corwin.

Ann Ebe is an associate professor and coordinator

of the Childhood Education program at Hunter College in New York City.

Previously, Dr. Ebe served as their director of bilingual education and has

worked in schools as a bilingual teacher, reading specialist, and school

administrator in the United States, Hong Kong, and Mexico. Her latest book,

written with Drs. Freeman and Soto, is ESL

Teaching: Principles for Success.

Mary

Soto, a veteran secondary teacher of

emergent bilinguals and an associate professor in the Teacher Education

Department at California State University East Bay, now prepares teacher

candidates and master’s students to work with diverse learners. She is coauthor

of ESL Teaching: Principles for Success (Heinemann, 2016)

and Between Worlds: Second Language Acquisition in Changing

Times (Heinemann, 2021), and first author of Equitable

Access for English Learners (Corwin, 2020).

Yvonne

Freeman and David

Freeman are professors emeriti at The University of Texas Rio

Grande Valley. Both are interested in effective education for emergent

bilinguals. They present regularly at international, national, and state

conferences. They have worked extensively in schools in the United States and

abroad. The Freemans have authored books, articles, and book chapters jointly

and separately on the topics of second language teaching, biliteracy, bilingual

education, linguistics, and second language acquisition.