Designing a Whole-Class Approach to Supporting ELs

by Kimiko E. Lange, Rose K. Pozos, Annie Camey Kuo, Melissa Mesinas, and Shelley Goldman

Meet

Kristen,* a third-grade teacher with a small but increasing number of students

designated as English learners (DELs) in her classes each year. Despite more

than 10 years of classroom experience, she felt underprepared for and a little

overwhelmed by the task of supporting English language development for her

DELs. Sound familiar?

Supporting

DELs is the responsibility of all teachers, whether a 30-year veteran English

as a second language (ESL) specialist or a mainstream teacher with a single DEL

in their class this year. Readers may already be familiar with TESOL’s “6 Principles for

Exemplary Teaching of English Learners” (TESOL International

Association, 2018) as a guide to doing this. Certainly, it is hard to argue with

the value of principles such as “P1. Know your learners,” “P2. Create

conditions for language learning,” or “P6. Engage and collaborate within a

community of practice.” But how might one go about enacting these principles?

Read on to see an example of how Kristen, with a little help from an

unconventional teacher professional learning model, developed a strategy that

focused on DELs but ultimately supported her whole class.

A Fresh Take on Teacher

Professional Learning

Our project,

known as English Learners and Design Thinking (ELDT), began in 2017 (Goldman et

al., 2020). ELDT is part of a long-term research-practice partnership (Coburn

& Penuel, 2016) between university researchers and surrounding schools.

We work with 15 primary schools in five surrounding school districts to address

a mutually identified problem of practice: raising awareness of and support for

the needs of DEL students among teachers and administrators, and creating

curricular and systemic changes for their benefit.

As we

deepened our engagement with this work, we came to use the abbreviation “DEL”

in lieu of the more common “EL.” This serves as a reminder that the latter is

merely a designation—a label placed upon students by our school systems that so

often implies that these students are somehow not up to the task of learning,

instead of highlighting their rich cultural, linguistic, academic, social, and

experiential assets.

As we

deepened our engagement with this work, we came to use the abbreviation “DEL”

in lieu of the more common “EL.” This serves as a reminder that the latter is

merely a designation—a label placed upon students by our school systems that so

often implies that these students are somehow not up to the task of learning,

instead of highlighting their rich cultural, linguistic, academic, social, and

experiential assets.

To support

teachers and administrators attend to their DELs’ potential, we use a

combination of design thinking (Goldman & Kabayadondo, 2016) and hybrid

workshops (Rutherford-Quach et al., 2018) as a new take on professional

learning.

Design

Thinking

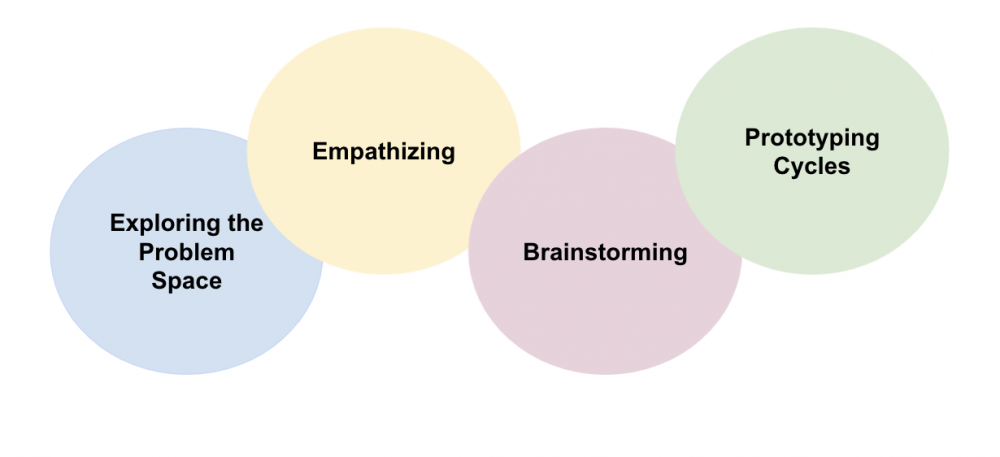

Design

thinking is a set of mindsets and practices that relies on an empathy process

to support active teacher learning and engagement. The process is flexible (see

Figure 1), with the teacher cycling through iterations of discovering their

user’s needs (in this case, their DEL student), figuring out what issues are

presenting challenges for them, and intentionally engaging their own empathy to

draw out fresh insights to inform design solutions.

Figure 1. The Design thinking process: A method for

solving complex problems. (Used with permission from Shelley Goldman, Stanford

University; click here to enlarge.)

In ELDT,

teachers apply design thinking by starting each year with an empathy project.

They select a DEL “focal student” in their class for whom to design, then

gather data about them through methods such as observations, surveys, and

interviews. They analyze what they’ve gathered to figure out the challenges,

needs, and resources of their student, then brainstorm and prototype ideas for

possible interventions. Over many months, teachers try out their interventions

and iterate on them, learning from failures and feedback to design subsequent

iterations and track their effectiveness through each.

Hybrid

Workshops

Hybrid

workshops support teachers’ designing process by offering timely research on

DEL topics, which the teachers bring to the forefront in the learning

prototypes they create for their students. Content and resources are cocreated

by members of the research-practice partnership to be as relevant as possible

to the DELs’ specific contexts. Workshops occur both virtually and in-person

throughout the year, facilitating not only the development of knowledge and

strategies, but simultaneously engaging teachers in the empathy-driven design

thinking process through discussion, reflection, and application.

Examples of

workshop topics include

-

“Social Emotional

Well-Being” (developing a line of communication between teachers and DELs’

families)

-

“Dually Identified

Students” (supporting DELs who are also receiving SPED services

-

“Constructive Classroom

Conversations” (facilitating student-to-student conversations and enhancing

pair-share activities)

Several

teachers in our project found the workshop on “Constructive Classroom

Conversations” (based on materials developed by Understanding

Language) particularly helpful as an integrated approach they could

take to enhance language support for DELs in their classrooms. We illustrate

one such case with Kristen’s story.

Kristen’s Design: From

One to Many

Recall

Kristen, a veteran teacher who wanted to improve her instruction for DELs in

her third-grade classroom. She joined the project alongside two fellow teachers

and her principal.

Kristen

began her design thinking cycle at the start of the school year with her

empathy building activity: observing her focal DEL student, Sonia. Initially,

she noted that Sonia was “very quiet.” “I just didn’t see her bonding with

friends,” she observed. Through this activity, Kristen realized she needed to

take time to learn what Sonia was experiencing in the classroom. She would need

to set up her classroom in a way that would help Sonia feel more comfortable

talking.

Following

the design thinking cycle, Kristen conducted further observations. This time,

she noticed that Sonia was

involved in

listening, reading to herself and writing her group’s main idea sentence in her

Reader’s Workshop journal.…She talked once, but so quietly, I don’t think

others heard. [However,] she was fully engaged in the activity as an active

listener and recorder.

These

observations launched Kristen’s prototyping phase of design thinking. Inspired

by the “Constructive Classroom Conversations” hybrid workshop, Kristen teamed

up with two colleagues to redesign their daily morning meeting routines, to

incorporate a way for their students to learn about elements of conversation.

Three times a week, student pairs conversed on nonacademic topics by using

sentence starters. In her class, Kristen set Sonia up in a purposeful

partnership with a classmate to help create a social bond, which played a

crucial piece in leveling the languaging playing field.

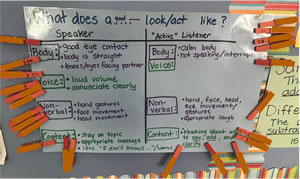

At first,

Kristen couldn’t hear what Sonia was saying, which made it difficult to

determine her progress. So she iterated and codeveloped a skills poster with

her colleagues (Figure 2). The poster outlined how a “good speaker” and an

“active listener” might look, sound, and behave. Each student would choose a

conversational skill to work on that day, and place a clothespin with their

name next to it. At the close of their morning meeting, their conversation

partner would provide feedback on how they met their goal. With this one

change, Kristen expanded her support for conversational skills from being

focused on Sonia to meeting a whole-class need.

Kristen

shared that the poster was empowering for students, including but not limited

to DELs. It provided structure, in the form of a visual, but also in its

predictability (when they’ll practice what) and social motivation (partners).

Every student worked on their respective goals over extended periods of time,

in a way that held them accountable to one another. Soon, Kristen was able to

hear Sonia speak and stay on topic. As Sonia continued to make progress,

Kristen continued to build on her social conversations by integrating these

speaking skills with academic activities. In the next school year, Kristen and

her colleagues rejoined our ELDT project in order to continue refining their

model.

Figure 2. Kristen’s conversation board. (Click here to enlarge.)

Characteristics

of Success

What made

Kristen’s design so successful? Certainly a combination of factors, but three

characteristics of Kristen’s case stood out across the educators who seemed to

have the most success with their prototypes and reported transformative results

engaging their DELs.

Embracing

Empathy

First, these

educators embraced empathy. Observing students may have already been part of

their practice before ELDT, but embracing empathy was what really helped them

gain more information and new insights about their students. Teachers who

embrace the empathy process develop a heightened focus on the social nature of

language acquisition and positive or more nuanced perceptions of DELs. Like

Kristen and Sonia, teachers observed their DELs become more engaged and

comfortable communicating. They also expressed understanding of the importance

of creating a welcoming classroom environment for DELs.

Failing

Forward

With the

information they collected and new insights they gained, the teachers were able

to try different innovations, adjusting them as they saw what worked and what

didn’t. This embodies the second design thinking characteristic we noticed:

failing forward. Kristen, her colleagues, and other educators in our project

constantly iterated on their designs, seeking and incorporating students’

feedback along the way instead of giving up. They used information from their

so-called “failures” to design better iterations for their students each time.

Finding

Partners

Finally,

finding partners in designing innovations frequently led to more success. We

like to think that Kristen not only found her fellow teachers as partners, but

enlisted her students as well, taking a whole-class approach to supporting

DELs—and benefiting all students in the process.

Conclusion

We offer our

project as an example of how educators can improve their support of students

designated as English learners using design thinking. From Kristen’s example,

we saw how insights about one student’s experience can provide inspiration for

whole class instruction. However, the key to supporting DELs does not lie in

any singular design; what is more important is the mindset of the teacher and

their willingness to observe carefully, embrace empathy, fail forward, and find

partners in their work. This can yield fresh insights that lead to more

effective supports for language development.

*NOTE: All

participants’ names are pseudonyms.

References

Coburn, C.

E., & Penuel, W. R. (2016). Research–practice partnerships in

education: Outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educational Researcher,

45(1), 48–54.

Goldman, S.,

& Kabayadondo, Z. (Eds.). (2016). Taking design thinking to

school: How the technology of design can transform teachers, learners, and

classrooms. Routledge.

Goldman, S.,

Kuo, A. C., Pozos, R. K., Mesinas, M., & Lange, K. E. (2020).

Empowering teachers through design thinking. RChD: creación y

pensamiento, 5(8), 37–48.

https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-837x.2020.55992

Rutherford-Quach, S., Kuo, A. C.,

& Hsieh, H. (2018). Understanding their language: Online professional

development for teachers of ELLs. American Educator,

42(3), 27.

TESOL International Association.

(2018). The 6 principles for exemplary teaching of English learners:

Grades K–12.

Kimiko E.

Lange taught ESOL and Japanese for 8 years before

beginning her PhD at the Stanford Graduate School of Education. Her research

and activities focus on multilingual teachers, teacher education, and how

teachers share authority with students through language. Creativity and careful

observation are design thinking features she hopes to cherish in her own work

and with others.

Rose K.

Pozos is a PhD candidate in the Learning Sciences and

Technology Design program at Stanford University. She studies design thinking

to support curriculum design, linguistically equitable computer science

education, and home-based learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Annie Camey

Kuo is the director of research-practice partnerships

for Understanding Language – Center to Support Excellence in Teaching at

Stanford University. Her work focuses on building systems of support for

multilingual students with schools, states, and organizations. Before coming to

Stanford, Annie worked with teachers and international school leaders in

supporting culturally and linguistically diverse students at the University of

Washington. Her areas of interest include design thinking, project-based

language learning, and multilingual learners.

Melissa

Mesinas is a consortium for faculty diversity

postdoctoral fellow and visiting assistant professor at Scripps College. Her

research focuses on the development and learning process of youth within the

contexts of Indigenous diasporic learning communities, and design thinking to

support multilingual students.

Shelley

Goldman is a professor at the Stanford Graduate School

of Education. She is a former elementary and middle school teacher and helped

to start three public schools. She works with teachers and administrators on

using design thinking to create truly meaningful and transformative learning

experiences for K–12 students.