Scaffolding Independent Think-Aloud Activities

by Becky Bonarek and Trischa Duke

A Think Aloud (TA) is a learning strategy in which the learner verbalizes what they are thinking as they complete a task. There are a couple of notable benefits of using TAs. First, TAs can be used to model the moves that expert readers make. Second, TAs allow instructors to observe aspects of receptive skills that were previously locked inside students’ heads, and as a result, instructors can give more targeted and effective feedback or implement additional support strategies. For this article, we focus on using TAs in a reading classroom in a higher education context; however, the ideas put forth can be adapted to various contexts at various levels.

Our reading support course is designed for international college freshmen enrolled in developmental writing (English for Academic Purposes) courses to prepare them for freshman composition and other undergraduate content courses. We noticed that though our students were generally able to preview texts and activate prior knowledge while reading on their own, they ignored or hesitated to use many advanced moves made by expert readers, such as questioning the text or recognizing bias. To train our students to access a variety of metacognitive strategies when reading, we implemented independent biweekly TA assignments (Appendix A) and developed a scaffolded framework categorizing critical reading strategies into three levels of engagement with the text.

In this article, we describe the following:

- scaffolded reading skills used by students in our TA assignment,

-

how to reinforce those scaffolded skills in class,

-

how to overcome some common problems that arise during the process, and

-

how to apply the scaffolding in other settings.

Scaffolding Skills in Think Alouds

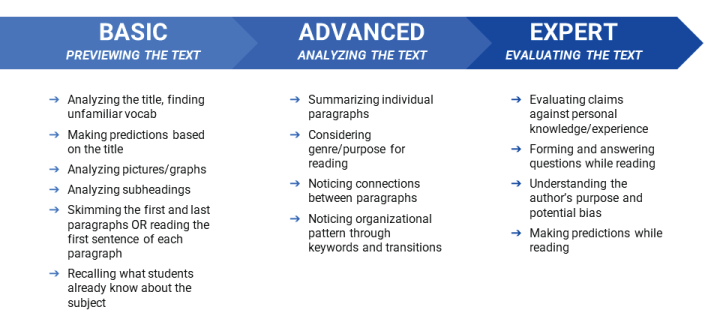

We identified 14 strategies of effective readers and organized them into three iterative levels: Basic (strategies to preview the text), Advanced (strategies to analyze the text), and Expert (strategies to evaluate the text). We outline the progression in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Scaffolded Think-Aloud strategies.

(Click here to enlarge.)

Basic Strategies

The Basic strategies are those that readers use prior to reading a text. These tend to be the strategies that our students most often use independently, because they are easier and occur before students get lost in the text. We introduce these strategies early in the semester, and students tend to pick them up fairly quickly.

Advanced Strategies

The Advanced strategies typically happen during reading and require readers to pause at strategic places throughout the reading process, such as at the end of each paragraph or logical grouping of paragraphs. Students move beyond comprehension and begin to interact with the text. These strategies generally take more training than the Basic strategies because they require readers to take a step back from reading to consider what they have read and how it fits together.

Expert Strategies

Expert strategies are used during and occasionally after reading. These strategies encourage readers to engage with the text on a more complex level by inferencing, questioning, and making connections outside of the text.

The Assignment and How to Scaffold the Skills

In our reading course, we assign seven biweekly TA assignments across the term. We have compiled newspaper and magazine articles into one electronic document on which they can annotate using the text annotation tool of their choice (usually Microsoft Word or Google Docs). For each TA, students read the assigned article and record themselves in a solo Zoom meeting with both screen sharing and camera turned on. Students then upload the recording to a designated folder in Google Drive for the instructor to evaluate using a feedback form (Appendix B) that students have access to as they record.

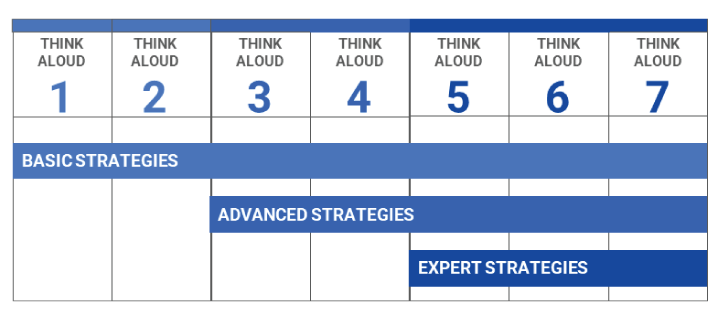

In the assignment (Appendix A), the strategies are scaffolded to give students the opportunity to practice, master, and make a habit of using easier strategies before moving on to more complex ones. In class, we model new strategies and provide guided practice for each and then encourage students to incorporate them into their independent reading. The skills are scaffolded in conjunction with how and (approximately) when they are introduced in class. To encourage use of a variety of strategies—and avoid an overreliance on some—students are required to use a certain number of strategies at each scaffolded level, and for the subsequent TA(s) at the same level, students must demonstrate at least one previously unused strategy.

Figure 2. When strategy levels should be demonstrated.

(Click here to enlarge.)

View example TA recordings online: Example 1 and Example 2.

Monitoring and Reinforcing Skill Practice

With so many skills in play, some of which students have not encountered in previous educational settings, it is essential to build in class time for monitoring and reinforcing the appropriate application of critical reading skills. Two items already mentioned in this article can help instructors monitor students’ skill usage: the feedback form and a skill usage goal.

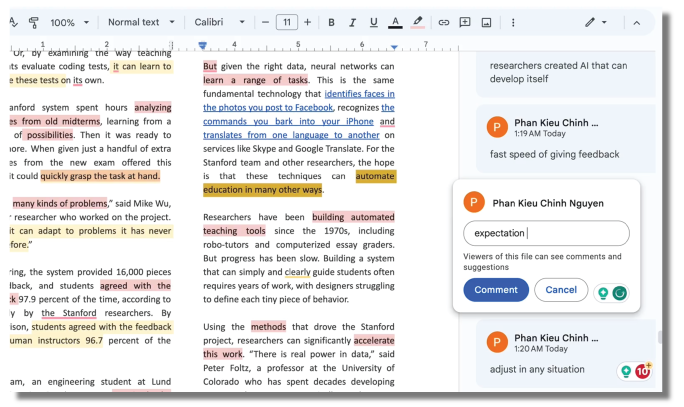

Figure 3. Screenshot of a student Think Aloud example.

(Click here to enlarge.)

First, a strategy/checklist feedback handout (Appendix C) helps keep both students and instructors on track. Create a checklist of the strategies required for each TA assignment; make it available to students before, during, and after recording their assignments; and leave feedback on the same form.

Second, as we mentioned before, giving a skill usage goal encourages students to demonstrate new or previously unused strategies by requiring students to practice a target number of skills for each TA. For example, we require students demonstrate at least three skills at each skill level; for the first time a student records a TA at a given level, all skills are new, but the second time they record, at least one skill must not have been attempted before.

Following are three strategies to reinforce skill practice:

-

Reinforce use of these skills during in-class work: During in-class exercises or practice, explicitly state when in-class work introduces or includes a TA skill. Provide repeated opportunities to practice the skills required at a given level, even when the skill isn’t the target of the lesson and (re)model how to perform the strategy in both TA and regular classroom settings. This strategy gives students skill practice and demonstrates that these skills should not be used only on isolated assignments.

-

Remind Students when new skills will be added/phased in: When assigning TA work, explicitly remind students (1) when they are progressing to the next TA skill level and (2) what skills are included in that new level. At each new level, review the feedback form with students in class, elicit or model definitions and examples of the skills listed, field questions, and remind students of how many skills are required. This strategy keeps the feedback form at the forefront of students’ minds while supporting the scaffolded nature of the assignment.

-

Review general feedback in class: The more you can incorporate your feedback form/checklist into class sessions, the better. Another way to accomplish this is to make general comments in class about the TAs’ strengths and opportunities for improvement the day after you grade them. This strategy not only revisits the feedback form but also reminds students to read their individual comments (with the bonus of giving anonymized feedback to students who don’t read their comments).

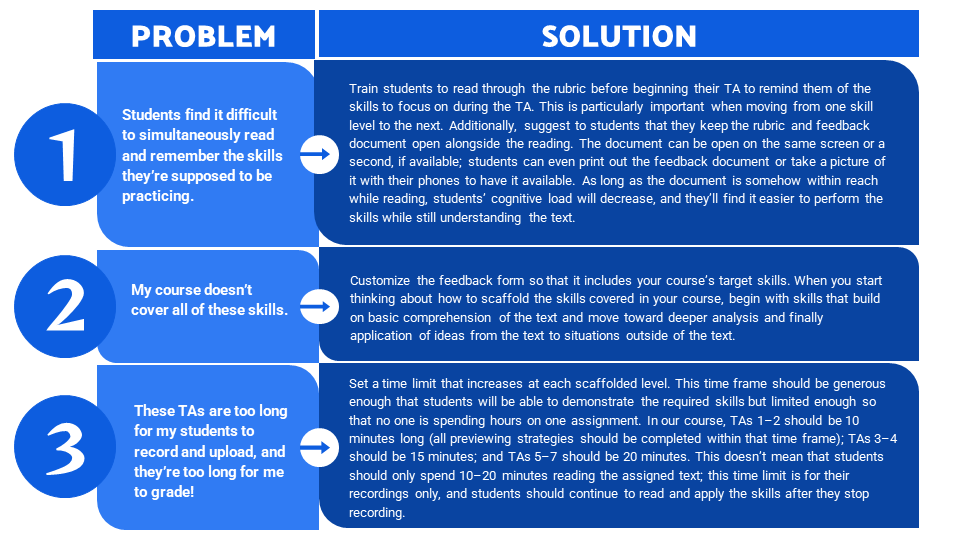

Common Problems and Solutions

To prevent fellow instructors from running into the same pitfalls as we have, we’ve collected the most common problems we’ve faced and our solutions to overcome them.

Figure 4. Chart of common problems with TA scaffolding and possible solutions.

TA = Think Aloud. (Click here to enlarge.)

Conclusion: Adapting Independent Reading Think Alouds to Other Learning Contexts

We’ve focused on university-level multilingual learners of English for the most part. However, if your learning population is different, we have some thoughts on how to scaffold the scaffolding. Typically, the process simply requires a bit more time and involvement on your part.

Following are general guidelines for adapting a scaffolded TA approach:

-

Take the time to curate which skills to focus on. Not all target skills in your course need to be included. Which ones will best set students up for success? For nonacademic-track students, what skills are most important in real-world situations?

-

Include fewer skills in each level. This helps students focus on skill improvement while avoiding comprehension loss or too much cognitive load.

-

Choose material carefully. This is particularly important when asking students to move beyond the text, or when using a scaffolded TA approach to a listening activity.

-

Model, and model often. For students with less reading background, referring to a previously recorded model (either instructor created or from a consenting student) can be a guide as well as a major confidence boost.

-

Do TAs live and one-on-one, if timing and student numbers allow. This allows you to guide the process and take some of the cognitive load off of the student while still completing the activity. As the term progresses, consider gradually removing yourself from the process and allowing the student to take over.

We hope that the scaffolding of these critical reading skills during TAs helps your struggling readers build their strategy toolbox while simultaneously deepening their reading practices. Happy reading!

Becky Bonarek is a lecturer at the University of Illinois Chicago’s Tutorium. She has an MA in applied linguistics/TESOL and a BA in French and English/creative writing with a minor in social change and public advocacy. She has taught in community/adult, for-profit, university, and EFL contexts. Her research interests include World Englishes, social/language justice and advocacy, and teaching reading and writing.

Trischa Duke is a senior lecturer at the University of Illinois Chicago’s Tutorium and is currently serving as Accelerator program chair, overseeing the Tutorium’s international undergraduate pathway program. She holds MA degrees in English and applied linguistics/TESOL, is currently working on an EdD in learning design and leadership, and has 30 years of teaching experience in various contexts. Her research interests include writing in an additional language, teacher development, and program evaluation.