ADVERTISEMENT

December 2012

|

I’d like some bacon and eggs. |

The above excerpt from comedian Shelley Berman’s classic “Rune Sor-bees” telephone exchange between a hotel guest and a room service clerk serves as a humorous but nonetheless very poignant reminder that comprehension between native and nonnative speakers of English can break down at the word or even syllable level. In fact, one of the fundamental activities when teaching pronunciation to second language learners is the teaching of segmental contrasts, i.e., the difference between two vowel or consonant sounds that are causing difficulties for students, either in terms of their perceiving the difference or in producing it (usually both).

These phonemes (or distinctive sound contrasts) may cause difficulties for students for two primary reasons:

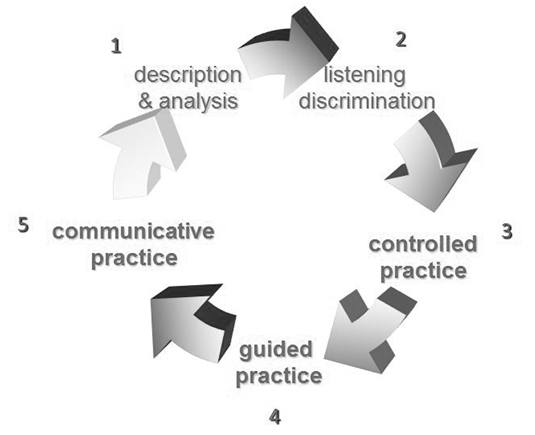

Celce-Murcia, Brinton, and Goodwin (2010) suggest that when teaching a segmental contrast, teachers use the five-part communicative framework in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A communicative framework for teaching segmental contrasts.

For more on this framework, see Celce-Murcia, Brinton, & Goodwin (2010).

To illustrate this teaching sequence, we can take the example of the vowel contrast /e/ as in bed and /æ/ as in bad–a contrast that again is problematic for speakers from a large range of languages.

Stage 1: Description and Analysis

At this stage, the teacher needs to clearly present the articulatory differences between the two sounds. To do so, a range of tools and techniques are available, such as the sagittal or profile diagram sketches commonly found in pronunciation textbooks that illustrate the position of the tongue with respect to the other articulatory organs as well as the passage of air through the oral or nasal passageway. (An excellent resource for teachers on segmental contrasts is Nilsen and Nilsen, 2010.)

Other techniques commonly used are “gadgets” (such as drinking straws or popsicle sticks) so that learners can more accurately feel the position of their tongue or kinesthetic techniques such as asking learners to place their hand palm down underneath their chin and practice the given vowel contrast (such as end vs. and), concentrating on the difference in the position of the jaw (i.e., higher for end and lower for and). As a small group activity, students can also be asked to sort a random list of words containing the key sounds into the two categories or make cue cards with sample words for each phoneme (possibly illustrating these with simple drawings). They can also, as a whole class activity, conduct a treasure hunt to locate classroom items containing the two key sounds.

Stage 2: Listening Discrimination

In listening discrimination, learners are given the opportunity to tune their ear to the sound differences. Techniques applied at this stage include word- and sentence-level practice with minimal pairs—words that differ by only one phoneme such as back and pack (for consonants) or pick and peck (for vowels). Traditionally, the teacher checks learners’ discrimination skills by reading the two minimal pair words and asking learners if they are the same or different. Alternatively, learners may be asked to identify the “odd man out” by identifying the word in a list that contains a different vowel phoneme. See Appendix A for examples of these activities.

Similarly, for minimal pair sentence practice, the teacher can read aloud one of the two sentence options (as in Appendix B) and ask students to indicate which sentence they heard by holding up one or two fingers. This task can also be done as pair practice, with students reversing the roles of speaker and listener.

An updated activity that puts a more communicative spin on minimal pair listening discrimination is pronunciation bingo, as in Appendix C. In this activity, the teacher distributes a bingo board to all students and instructs them to place a marker (such as a coin) on the square when they hear a word read aloud. They should call out BINGO when they have an entire row of Xs, either across, down, or diagonally. (Assuming all sounds are discriminated correctly, students should call out bingo at the same time.) Once students are familiar with the game, they can play it in small groups with one student assuming the role of bingo caller.

Stage 3: Controlled Practice

During the controlled practice stage, the learners’ attention is focused on correctly articulating the target sounds, with little or no use of original language. Examples of controlled practice include the reading aloud of sentences, tongue twisters, or short dialogues, as in Appendix D, Appendix E, and Appendix F; often these are done as pair practice, with one student reading and the other student monitoring and providing feedback, then exchanging roles.

Stage 4: Guided Practice

Guided practice combines a focus on the target sounds with the need for learners to use original language to accomplish the task. Typical activities in this stage of practice are information gaps and cued dialogues, as illustrated in Appendix G and Appendix H. The teacher’s role includes giving clear directives to students and also providing assistance to students who need assistance.

Stage 5: Communicative Practice

Stage 5 includes less structured practice and requires learners to attend to both the target pronunciation features and the content of the message being communicated. Typical activities are those that require original production of language such as storytelling, role play, and problem solving. Appendix I presents an adaptation of a story-telling activity in which the learners (in pairs or small groups) select 10–15 words from the word bank provided to produce an original story; they then present the story to their peers for feedback. A second sample activity for communicative practice involves students taking on the roles of fictional characters who are meeting for the first time (e.g., at a company affair) to practice engaging in small talk (as in Appendix J).

Conclusions

This article has suggested a five-stage process for teaching a segmental contrast, illustrating this process with a number of suggested activities at each stage. The sample segmental contrast chosen here is /e/ vs. /æ/; however, the five-stage process adapts to any segmental contrast (vowel or consonant), as do the suggested activity types.

Teachers are cautioned that the entire process of teaching a segmental contrast should be spread out over several lessons and not attempted in one single lesson as learners require time for the process of distinguishing and producing new segmental contrasts to become automatized. Finally, although the activities here are teacher-produced, many commercial ESL/EFL textbooks contain similar types of activities.

References

Berman, S. (1972). A hotel is a place. Los Angeles, CA: Price, Stern, & Sloan.

Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D., & Goodwin, J. (with Griner, B.) (2010). Teaching pronunciation: A reference for teachers of English to speakers of other languages (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Nilsen, D. L. F., & Nilsen, A. P. (2010). Pronunciation contrasts in English (2nd ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

__________________________

Donna M. Brinton is an editor, author, and private educational consultant. She is a retired member of the Applied Linguistics and TESOL faculty at the University of California, Los Angeles, and has been a faculty member at the University of Southern California and Soka University of America. She frequently conducts short-term teacher training and program evaluation. With Marianne Celce-Murcia and Janet Goodwin, she is the author of Teaching Pronunciation, 2nd ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

| Next Article |

ESL Faculty Positions (Full-Time), University of Delaware English Language Institute, Newark, Delaware, USA

Lead English Course Content Developer, ASAP Inglés, Bogotá

Assistant Professor of TESOL, West Chester University, Pennsylvania, USA

Intensive English Program Faculty (Full-Time), Spring International Language Center, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas, USA

Want to post your open positions to Job Link? Click here.

To browse all of TESOL's job postings, check out the TESOL Career Center.

Five fans of TESOL's Facebook page received free memberships when the page reached 60,000 likes. We have reached that benchmark! The lucky winners are:

Roya Ashtianinaia, Iran

Kiang Chui Tan, Malaysia

Erica Morrison, Canada

Beatriz Ramos-Martinez, USA

Andrea Karla Wei, Philippines

Each will receive a free Professional Membership and enjoy full membership benefits. Congratulations to the winners, and thank you to all who support TESOL on Facebook.