ADVERTISEMENT

June 2013

All teachers want their students to succeed. For ESL students, intelligibility—whether they are understood by others—is vital for their language success. In many cases, even a perfectly worded phrase is not enough. The wrong intonation (or stress), or the lack of any intonation when speaking, may cause miscommunication. The purpose of intonation is to help the listener to follow (Gilbert, 1994). ESL teachers are in a unique position to guide their students. How can teachers help students understand the concept of intonation as it relates to intelligibility? The following activity has worked quite well for me.

Let’s study Chinese!

(No previous knowledge of Chinese required! Just spend 1 or 2 minutes with the recordings and you will be ready)

| Tools: One large flipcard with three phrases, or the provided PowerPoint slides with sound files: askme (wma), smellme (wma), kissme (wma), verygood (wma) |

| Level: Beginner to advanced |

| Duration: 10–15 minutes |

Note: If you are lucky enough to have Mandarin Chinese-speaking students in your class, please have them assist you!

The goal of this activity is to help students (and teachers—I did this at a workshop at the 2013 TESOL convention) understand the concept and importance of intonation as it relates to intelligibility by teaching them three phrases of Mandarin. I try to do this activity right at the beginning of the semester but it can be done at any time. In preparation, you may either put the following three phrases on one large card, use the PowerPoint link with your own computer, or print out the PowerPoint slides.

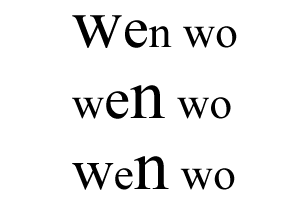

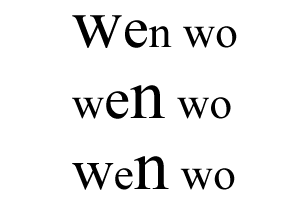

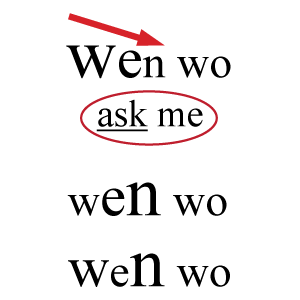

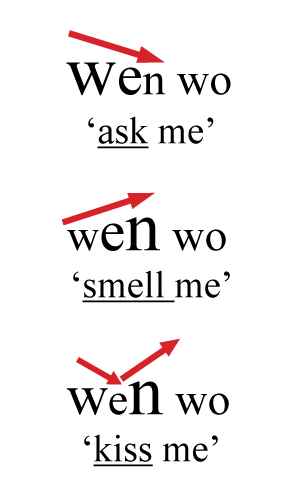

Some background on the Chinese language: What teachers should first notice in the three phrases is that the word wen is written differently in each phrase, with letters of varying sizes. Why varying sizes? Chinese is a tonal language, and the direction of the tones used here (falling; rising; falling then rising, respectively) determines the meaning of the words. To visually demonstrate the tonal direction, I am using the size of the letters.

In phrase 1, the tone for wen is falling. This wen means “ask” me. Listen.

In phrase 2, the tone is rising. This wen means “smell” me. Listen.

In phrase 3, the tone is falling, then rising, like a checkmark. This wen means “kiss” me. Listen.

Similar to our students when they are speaking English, if we get Chinese tones right, our desired communication is achieved. If we get them wrong, confusion ensues.

It is important not to reveal the meanings until the students have said each phrase somewhat intelligibly with the proper intonation. Twice is usually enough.

Sample Dialogue

T = Teacher

Ss = Students

Phrase 1

T: Look at the three phrases.

T: Which word looks strange or different in all three sentences?

Ss: Wen.

T: Yes, now look at the first phrase.

I will say/play the first phrase two times. Listen, and tell me what happens to the wen. Does it go up, does it go down? Is it flat? [T then says or plays the phrase]

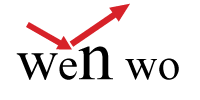

Ss: Wen goes down. (If they say “up” or they don’t know, just say it/play it again. If they still do not hear it, try saying the phrase in slow motion. That, and the exaggerated and slow lowering/raising of your head always works and can get a lot of laughs, too. Remember—this should be fun). Once you have elicited the correct direction, using a marker, you can mark the direction (down, up, or checkmark) over the word wen, or simply click on the PowerPoint to show the direction.

Say the phrase together once more, and then reveal or write the meaning underneath the first phrase (see image below). If you are using PowerPoint, simply click to reveal the meaning.

Students tend to get pretty excited here, as most of them have probably never spoken a Chinese phrase before. (By the way, feel free to say hen how here. It means “good job” in Mandarin. Listen.)

The presentations for phrases 2 and 3 follow in the same manner. Continue to mark the direction (or click on the PowerPoint) after eliciting the direction from the students. You should notice that Phrase 3, with a ”checkmark” tone, is a little longer than the others.

Once you have done each phrase, put the card up on the board with all three English answers. It should now look like this:

More Practice

You can then practice three ways: Teacher-to-class, student-to-class, and student-to-student.

Teacher-to-Class

T: I will say one of the phrases. Please listen, then tell me the English.

[If they are mistaken, you can help them by gesturing what you wanted to say—motioning to have them “ask” you, or presenting your cheek for someone to “kiss.” Have fun with it.]Student-to-Class

T: Who wants to try?

[Have a student come up and do the same with the class. Again, if you have Mandarin speakers in the class, it’s fun to involve them in the “judging” as well as the teaching. You can be off to the side both to judge and help if needed.]Student-to-Student

T: Let`s make pairs. Work with a partner. Student A says a phrase in Chinese. Student B has to guess the phrase. Then switch. Go slowly.

Circulate to make sure students are on task and also to see if you can understand each of them. Once everyone has had an opportunity to speak a little Chinese, review each phrase together and give them a big hen how (“Good job!”). You may then take a couple of minutes to emphasize how changes in the tone affect the meaning of the sentence, how English is no different, and how a system of marking the intonation with the marker/pen/pencil can be helpful whenever practicing.

Follow-Up Activity

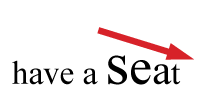

A quick follow-up/review could be with an idiom they all know, like “have a seat.” Ask everyone to stand. Do a few stretches. Then, without any obvious gesturing, suddenly say “HAVE a seat,” making sure to emphasize have and not seat. Say it again once or twice. Say it slower, still emphasizing have. Most students will have no idea what you are saying or asking them to do. Gradually, some students may understand and sit down. Finally, say it properly, and everyone should get it and actually sit. Discuss what happened, write the idiom on the board, elicit where the proper intonation should be (seat), mark it on the board, and have them practice it.

Other idiom examples you might use are “what’s up?” or “take care.”

For homework, ask them to choose an idiom they know well and mark it in the same manner. You can have them present on the board and discuss in the next class.

As English continues to become a global language, it is important for ESL/EFL teachers to equip our students with whatever tools we can to help them get a leg up. Teaching them about intonation, and providing them with a forum to practice, is important for their success.

Reference

Gilbert, J. B. (1994). Intonation: A navigation guide for the listener. In J. Morley (Ed.), Pronunciation pedagogy and theory (pp. 36–48). Alexandria, VA: Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages.

|

Download this article (PDF) |

____________________

Andrew Schneider has been teaching ESL/EFL for more than 20 years, and has taught in Japan, Spain, and the United States. He currently teaches medical students in Kanazawa, Japan, at the Kanazawa Graduate School of Medical Science.

Disney English Foreign Trainer, Disney English, Multiple cities in China

Full-Time Lecturer, Department of Linguistics (TESOL area), Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois, USA

Lecturer (non-tenure-track), Southern Illinois University, Rural

U.S. Embassy Projects - Senior Fellow, U.S. Department of State English Language Fellow Program, Worldwide

Want to post your open positions to Job Link? Click here.

To browse all of TESOL's job postings, check out the TESOL Career Center.