ADVERTISEMENT

November 2015

Comprehensible pronunciation is essential for effective communication. However, in many IEPs, as in other ESL and EFL contexts, the absence of stand-alone pronunciation classes means that pronunciation instruction must be crammed in to already jam-packed speaking/listening or reading/writing curricula. Moreover, research suggests that in communicative classrooms, we focus on pronunciation only 10% of the time (Foote, Trofimovich, Collins, & Soler Urzua, 2013), and when we do manage to address pronunciation issues in our lessons, it tends to be in a corrective capacity rather than an instructive one (Levis & Grant, 2003).

For teachers who are interested in including more pronunciation instruction in interactive and fun ways, here is a toolkit made up of (mostly) everyday items.

Rubber Bands

Whenever students learn new vocabulary words, it is essential for them to also learn how to stress the word correctly; otherwise, they run the risk of being misunderstood. According to Grosjean and Gee (1987), the stressed syllable of a word provides an access code to help listeners locate the word in our mental vocabularies. If the stress is wrong, we wind up searching under the wrong access code. A rubber band is a great tool for helping students feel and internalize the stress patterns of English words. I give one to each student and, as we are chorally repeating new words as a class, have them pull the rubber bands taut on the stressed syllable of the words. It adds an element of fun and physical movement to choral repetition and gives students multiple passes with new words.

Hands

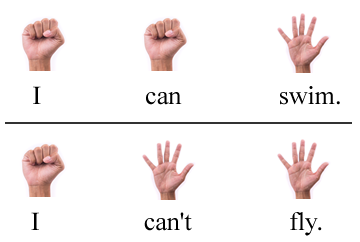

Like rubber bands, hand gestures can help students feel the seemingly irregular pace inherent to English speech rhythm. L2 learners often struggle to reduce the content words and highlight the focus words sufficiently. “It is common for students to emphasize every word when they are anxious to be understood. This gives the appearance of agitation or insistence that they may not intend, and it certainly diminishes the effectiveness of the prosodic ‘road signs’ that the listener needs” (Gilbert, 2008, p. 4). Therefore, it can be helpful to have students open and close their hands, as described in Grant (2010), while reading sentences. For instance, when we are reading sentences with can and can’t aloud, I often have students open their hands on the stressed words and make a fist on the unstressed words. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Hands for stressed and unstressed words.

Pencils

Often, in an effort to sound fluent, our students try to say everything as quickly as possible. However, when speakers don’t chunk their stream of speech into phrases, referred to as thought groups in pronunciation instruction, listeners may have trouble understanding them. Therefore, when I teach complex and compound sentences in my grammar lessons, I remind students that there is a tiny pause between the clauses when we read the sentence aloud and have them draw slash marks (/) where they hear it. This activity can also be very helpful for students who need to read dense academic texts, such as those found on the TOEFL or Cambridge CAE or CPE exams. Giving learners some time to slash longer sentences into thought groups and then reading the sentence aloud can help their reading comprehension enormously.

Kazoos

When proficient English speakers want to signal new information, contrast, or show strong agreement, they may rise and fall on a key word. Reed (2015) provides a great example of a misunderstanding between a professor and a student in the following conversation:

Student: Can I turn my assignment in late?

Professor: You can.

In this example, the professor’s pitch rises and falls on the word can. This musical quality of English, the intonation, can be daunting for our students to master. Even if students can hear the pitch change, they may not be aware that intonation “has the power to reinforce, mitigate, or even undermine the words spoken” (Wichmann, 2005, p. 229). In other words, in the conversation between the student and the instructor, the student hears the words and understands an affirmative message; however, the professor is, in fact, implying that he or she would prefer that the student didn’t hand in the assignment late. Kazoos can help students hear and produce these meaningful pitch changes in English, as they help to eliminate “all the distraction of other elements of speech, so that students can concentrate on the placing of pitch changes” (Gilbert, 2008, p. 35). I have found this to be especially useful when students are reading dialogues aloud. I just choose a few sentences and have students hum them into their kazoos so they can really feel the pitch changes.

Smartphones

Many teachers may shake their heads in disbelief, but I encourage students to bring their smartphones into some classes. Not only do I love the convenience of the dictionary apps, but I also make great use of their recording capabilities. Specifically, it can be very useful for students to make short (1–2 minute) recordings of themselves, whether in a monologue or conversation, and then transcribe their speech. They should also mark the target pronunciation feature on the text as they hear themselves use it. For example, if we are working on linking like consonants, such as in the phrase “some money,” when we link the final /m/ on some with the initial /m/ on money, the students would draw lines under all the places they heard themselves link. Then, for homework, I have them use a different colored pen to correct their linking errors, usually to add new underlines where they should have linked. Then, after I check their transcriptions, they can re-record their speech, taking care to link appropriately.

Mirrors

Students often have difficulty moving their mouths in ways that are necessary to form accurate English consonant and vowel sounds. While mispronunciations of these sounds don’t necessarily cause many breakdowns in communication, it can be beneficial and reassuring for students to work on the sounds that they love to hate. However, learners are often unaware of what their mouth is actually doing as they are struggling to reproduce a tricky consonant or vowel sound. When this is the case, it can be extremely helpful for students to watch my mouth as I am saying a word containing the target sound and then repeat the word while looking in a mirror. Mirrors help students to see more closely and mirror (pardon the pun) the accurate pronunciation of a sound, so they are more likely to pronounce it correctly in the future.

From lollipops to lemon juice (Noll, 2007) there are many more tools teachers have at their disposal to help their students master English pronunciation. These are just a few items I keep packed in my little teaching bag and haul along to most of my classes. Comprehensible pronunciation can be intimidating and frustrating for international students, but teachers can help with a little proactive explicit instruction and fun, active practice using some of the tools from their toolkits.

References

Foote, J. A., Trofimovich, P., Collins, L., & Soler Urzua, F. (2013). Pronunciation teaching practices in communicative second language classes. The Language Learning Journal. doi: 10.1080/09571736.2013.784345

Gilbert, J. B. (2008). Teaching pronunciation using the prosody pyramid. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Grant, L. (2010). Well said (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Grosjean, F., & Gee, J. (1987). Prosodic structure and spoken word recognition. Cognition, 25, 135–155.

Levis, J., & Grant, L. (2003). Integrating pronunciation into ESL/EFL classrooms. TESOL Journal, 12(2), 13–21.

Noll, M. (2007). American accent skills: Vowels and consonants. Oakland, CA: The Ameritalk Press.

Reed, M. (in press). Listening to what is meant—Illocution. In T. Jones (Ed.), Pronunciation in the classroom: The overlooked essential. Alexandria, VA: TESOL Press.

Wichmann, A. (2005). Please - from courtesy to appeal: The role of intonation in the expression of attitudinal meaning. English Language and Linguistics, 9(2), 229–253.

|

Download this article (PDF) |

Tamara Jones has been an ESL instructor for more than 20 years. She has taught in Russia, Korea, England, Belgium, and the United States. She is currently the ELC Intensive Program coordinator at Howard Community College in Columbia, MD. Tamara holds a PhD in education from the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom and is the coauthor of Q: Skills for Success, Listening and Speaking 4 and There Must be 50 Ways to Teach Them Pronunciation.

| Next Article |

Adjunct EFL Instructors (Spring Semester), Clark University, China

Senior Lecturer, ESOL (Nontenure Track), Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA

Director of ELI and Correspondence Education, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma, USA

ESL Lecturer (Core Faculty Member), University of North Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, North Carolina, USA

To browse all of TESOL's job postings, check out the TESOL Career Center.