Imagine you are in a foreign country learning not only a new language, but also content. Your classroom teacher has the following learning goal posted on the board:

Ich werde…beschreibe die Hauptfiguren mit Beweisen aus dem Text.

If only you had some idea what it all meant. Though you recognize some of the letters and possibly a cognate, the sum total of the message is incomprehensible. Now, let’s imagine for the sake of this article that the country is the United States and the language is English.

I will…describe the main characters with evidence from the text.

The task of moving English learners (ELs) to proficiency in both English language development and academic standards achievement is monumental, but attainable when supported with both appropriately scaffolded content lessons and language instruction based on practical English as a second language theory and methodology. Consider our learning goal in terms of content and grammatical forms and functions. The conscientious classroom teacher will be sure that their students are familiarized with the academic language necessary to access the content standards, in this case a lesson in English language arts. Vocabulary such as describe, main characters, and evidence from the text can be made comprehensible through visuals and anchor charts (see Figure 1).

I will…describe the main characters with evidence from the text.

Figure 1. Main

characters anchor chart.

However, knowledge of academic content vocabulary alone is not enough to close the achievement gap. Students need explicit and systematic instruction in the grammatical forms and functions of language to express their thoughts and ideas both in speech and writing. Saunders et al. (2013) advised that English language development instruction should include not only vocabulary, but also syntax, morphology, functions, and conventions. Consider, again, our learning goal, but this time through the lens of grammatical forms and functions:

I will…describe the main characters with evidence from the text.

In this sentence, we identify the future tense, articles, and prepositions. Though native English speakers may have picked up these aspects of language from countless exposures from birth on, our beginning ELs will need explicit instruction with these grammatical forms, many of which serve as “connective tissue” holding sentences, laden with academic vocabulary, together. When ELs are not afforded instruction with these seemingly simple grammatical forms, they later struggle when confronted with expanded and complex sentences. This article includes three strategies that, when used on a routine basis, can accelerate language acquisition among Beginning ELs.

Strategy #1: Focus on the Sentence Using Grammatical Forms and Functions

Though helping students at the beginning levels of English language acquisition build their academic content vocabularies is important, it is vital that we build them in tandem with sentence-level formation strategies. The simple sentence, subject-verb and subject-verb-predicate, is the basic building block for communication and paves the way for the development of compound and complex sentences further down the road. This requires that we teach our ELs the vocabulary of grammatical forms. Ramirez-Suarez and Shahadi-Rowe (2019) stated,

As students are equipped with the specific vocabulary associated with the unique purposes for writing, they can grow as autonomous writers who are able to use precise language to express their thoughts in more sophisticated ways that will meet college and career demands. (p. 33)

When we equip our ELs with the know-how of forming simple sentences, we help them take the first step toward college and career readiness. This equipping includes explicit instruction with the basic forms and functions of language, such as those on the ELD Matrix of Grammatical Forms (Dutro et al., 2007). A knowledge of basic grammar will allow students to move beyond word-level communication to sentence-level communication, an often neglected aspect of language instruction. ELs and native English speakers alike receive lots of support with learning vocabulary at the word level. An understanding of academic vocabulary, such as describe, characters, and evidence, is useful; however, without a knowledge of basic grammatical forms and how they work, beginner ELs will be ill-equipped to string words together to form coherent sentences that will ultimately enable them to succeed when tasked with writing assignments, such as paragraphs and essays, at the discourse level. Our job as teachers is to give beginner ELs knowledge of sentence-level constructs.

We can help our beginner ELs build academic discourse, one sentence at a time, by insisting that they routinely answer questions and express their thoughts in complete sentences. Remember, native English speakers had the luxury of hearing vocabulary embedded in sentences countless times before producing them in their speaking. By providing activities that include repetition, we can help solidify the acquisition of subject pronouns, verbs, and other grammatical forms. For example, when teaching students basic classroom vocabulary, include communicative activities that require students to use the vocabulary in complete sentences, preferably asking and answering questions to simulate authentic conversations. One of my favorite activities is Twenty Questions (Appendix A), which requires the use of what I have dubbed as the High-Utility Verbs (Appendix B), such as to want. When teachers use a progression of grammatical forms, it helps lower the chances that gaps will exist in their ELs’ language acquisition.

Strategy #2: Teach Vocabulary Within the Context of Grammatical Lexicons

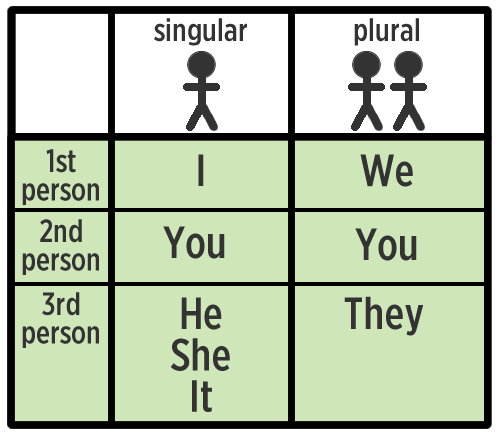

We can help accelerate our students’ learning of English by organizing grammatical forms into meaningful lexicons, or groups of related words. We know that ELs rarely acquire new language after one exposure. By organizing the grammatical forms in meaningful ways, we not only help students retain the information, but we also help them to retrieve it once our lesson is over.

We have all been there. We teach a mini–grammar lesson on subject pronouns, complete with total physical response and activities to provide multiple repetitions for students developing their receptive and productive language, all at the sentence level. However, we teachers become discouraged when 1 week later our students fail to use the correct subject pronouns in their speaking or writing. Research and experience tell us that students need many repetitions with new content before mastery occurs. So, how will we provide a way for our students to access the grammatical forms and their uses in the future when our mini-lesson is a distant memory?

Lexicon: Subject Pronouns

Figure 2. Lexicon

anchor chart.

Making lexicons available to students for future reference, in the form of an anchor chart (see Figure 2) or an entry in a student notebook, can provide our ELs with a valuable tool when attempting to produce language, especially at the sentence level.

An analysis of sight words and basic vocabulary that all students are expected to know with automaticity at the elementary level reveals that the majority of these words include common verbs and other basic grammatical forms, such as nouns, adjectives, pronouns, prepositions, and conjunctions. Now, consider the organization of these sight words in most elementary classroom word walls. Typically, the words are alphabetized, but rare is the learner who stores or retrieves sight words by the first letter of a word.

One useful tool for helping beginner ELs access lexicons of grammatical forms and their functions is the Writer's Placemat for Beginner ELs (Appendix C). This writer’s tool explicitly organizes the grammatical forms into lexicons by their functions. Our brains look for meaningful patterns when storing and retrieving information, a fact that makes arranging vocabulary into lexicons by their functions a powerful teaching strategy.

Strategy #3: Use Timelines to Teach Grammatical Forms and Functions

The use of timelines is often confined to social studies classrooms. They are a staple when teaching history to help students understand the chronology and context of events, as well as continuity, or the duration of an event. Though the most innovative teacher may include the use of timelines in the language arts classroom as a story is read to recount the order in which events occurred, their use can also be a powerful tool when teaching grammatical forms and their functions:

- Tenses: Use timelines from the beginning to teach tenses. Introduce the timeline along with signal words that indicate which tense should be used (see Figure 3). Start with the most basic signal words, such as yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Include these words as part of a daily routine: “Today is Tuesday, May 2, 2020.Yesterday was Monday, May 1, 2020. Tomorrow will be Wednesday, May 3, 2020.” As students become familiar with these signal words, begin to add to the lexicon of phrases, such as last week, right now, and next year.

Figure 3. Example

timeline to teach tenses.

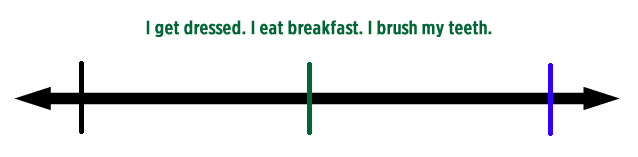

- Prepositions of Time: Once beginner ELs are familiar with the concept of timelines, you can use them as a context in which to teach prepositions of time, such as before and after to indicate the chronology of events. The following timeline example (Figure 4) shows chronology within the present tense and can help students better grasp the meaning of prepositions: “I get dressed before I eat breakfast. I brush my teeth after I eat breakfast.”

Figure 4. Example

timeline to teach prepositions of time.

Figure 4 lays the bedrock for the subsequent teaching of chronology in the past tense, “I got dressed before I ate breakfast,” and in the future tense as well, “I will get dressed before I eat breakfast.” Pictures of the actions may be added to the timeline to provide additional comprehensible input for students.

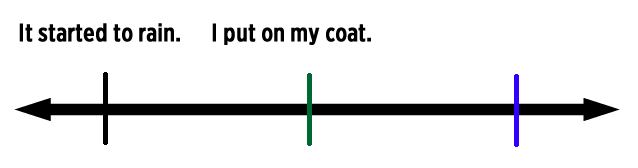

- Cause and Effect: Students’ understanding of cause and effect is bolstered through the use of timelines. If the concept of time has been reinforced routinely in a classroom, beginner ELs will quickly understand that with cause and effect relationships, one event precipitates another. Timelines become a vital tool in crafting cause and effect sentences with appropriate syntax modeled by the teacher. In the example, “It started to rain, so I put on my coat,” students are able to comprehend, with the aid of a timeline, the cause and effect relationship (see Figure 5). Additionally, offering students more than one way to produce cause and effect statements, with teacher modeling of syntax, accelerates language. For example: “I put on my coat because it started to rain.” As soon as students have mastered the conjunction so and because, encouraging them to use other vocabulary from the cause and effect lexicon, such as therefore and as a result, will bolster their vocabularies.

Figure 5. Example

timeline to teach cause and effect.

Concluding Thoughts

Though simultaneously learning English and content standards can be challenging, we can accelerate our ELs’ journey along the path of English language acquisition through routine strategies. Informing instruction through the use of a progression of language forms to help students build coherent sentences is the first step. In addition, organizing grammatical forms into lexicons based on their functions helps students not only better understand the forms, but also helps with retrieval. Finally, using timelines to teach tenses, prepositions, and conjunctions is an effective tool for providing comprehensible input.

References

Dutro, S.,

Prestridge, K., & Herrick, J. (2007). ELD matrix of grammatical forms.

E. L. Achieve. http://www.elachieve.org/images/ela/symposium/1s3_seceld

_distillinglanguage_post/seceld_tab211_13_matrix_tan_062209.pdf

Ramirez-Suarez, W. J., & Shahadi Rowe, C. (2019). Challenging English learners to improve academic discourse. The Pennsylvania Administrator (Winter).

Saunders, W., Goldenberg, C., & Marcelletti, D. (2013). English language development: Guidelines for instruction. American Educator, 37(2), 13–39..

Dr. Carmen Shahadi Rowe earned her master’s in TESOL from Eastern Mennonite University and her doctorate in educational leadership from Immaculata University. She has 20 years of experience in public education teaching Spanish and ESL, K–12. She serves as an ESL instructional coach in the School District of Lancaster in Pennsylvania, teaches courses in higher education for teachers in training, and frequently presents trainings on topics related to education.