ADVERTISEMENT

July 2023

I have been teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) in different university contexts since 2010. Most of my teaching career was in Turkey. Teaching in general and teaching languages, in particular, is a curious profession. Most of the time, we, teachers, are underpaid, we overwork, and we may find ourselves working in difficult conditions. Similar problems that lead to language teacher burnout are highlighted in previous research (e.g., Acheson et al., 2016). On the other hand, teaching comes with great rewards. There are many driving forces that teaching provides, such as seeing the joy of my students when they achieve beyond their expectations, their everlasting gratitude, and the kindness you receive from them in return—these are some of the rewards that have kept me going.

These rewards, however, along with the challenges, also result in the building up of an emotion labor for teachers (Gkonou & Miller, 2021). Emotion labor is defined by Benesch (2018) as “conflict[s] between implicit institutional feeling rules and discourses of teachers’ training and/or classroom experience” (2018, p. 63). According to her poststructural stance, emotion labor is a dynamic notion and can be a possible tool of activism and agency. Emotions, ours and our students’, are integral to our profession. Positive emotions can contribute much to our everyday practice. Nevertheless, our language classrooms do not take place in a void. We are not living in a wonderland, and, oftentimes, the volatile world with all its turmoil infiltrates into our classrooms either through our students’ emotional states or ours, which is also quite normal.

One thing that has become apparent to me in my teaching career is that it can be very challenging to be an adolescent language learner. The year 2019 was a particularly stressful one for those working and studying at Turkish universities. In Turkey, there was a sudden rise in the suicide rate, particularly among young people, according to news reports (Hürriyet Daily News, 2020). This phenomenon did not leave the university unscarred. A conversation that I had with a colleague was particularly thought provoking for me; she told me how powerless she felt and that she had no idea what her students had been going through.

Revising the Language Classroom Ecology Through Action Research

Reflecting on her words, I decided to increase my understanding of my students’ experiences and emotions by creating a classroom ecology where learners were motivated to speak about their lives. Social-emotional learning (SEL) provided a blueprint for me in designing my EFL speaking module. According to SEL, designing programs and lessons that promote learners’ social and emotional competencies are of critical importance. Accordingly, the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL; 2013) proposes five competencies:

In English language teaching, aiming to develop language learners’ competencies to use language more effectively to better understand their feelings is of critical importance because language is a “tool for the restoration, support, and healing of [English learners]” (Pentón-Herrera, 2020, p. 6). With that in mind, I used CASEL’s competencies to design a participatory action research intervention that included EFL speaking tasks related to my students’ everyday challenges—these activities urged students to scrutinize stressful social situations and work together to find solutions using the target language.

Overall, participating students reported that they felt more engaged once they had opportunities to speak about their lives in the target language. I have recently published this practitioner research (Uştuk, 2022) here.

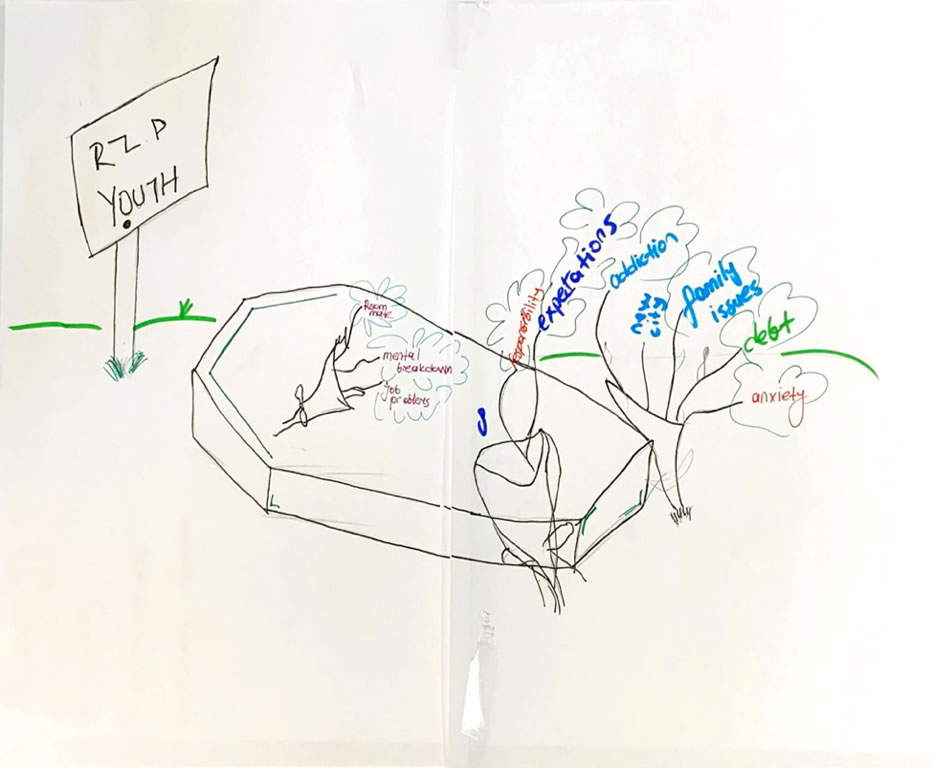

Figure 1. Student work: “Rest in peace youth.”

(Click here to enlarge)

Figure 1 shows a poster that one group of students produced. Using

This was just another signal for me as the teacher to understand how the events in 2019 and 2020 influenced my students. The findings of my action research showed that learners felt “honored” and “respected” to talk about these authentic issues affecting their lives on an everyday basis. As a language educator, the whole experience of using the target language as a tool, as Pentón-Herrera puts it, for “restoration, support, and healing” of my learners (2020, p. 6) was a fulfilling one.

3 Takeaways as a Language Teacher

To conclude, I would like to briefly reflect on my action research experience. Engaging in this practitioner research helped me to learn about my students’ lives and afforded me three takeaways as a language teacher:

1. Awareness: We teachers need to have a way to systematically take learner emotions into account in our teaching. We also need to use language as a tool for our students to better understand their emotions, which are mostly related to happenings beyond our classroom doors. An SEL framework helped me to do that.

2. Authenticity: The topics and concepts I ask my learners to engage with need to be relevant to their lives. This is not only about making our linguistic content more relevant to their practical needs but it is also humanizing our pedagogy and it is a matter of respect.

3. Achievement: Doing practitioner research helps me become a better teacher (e.g., by making my lessons more engaging). It also makes language teaching more fulfilling and less stressful as I better understand what is happening in and around my class.

Note: This article is an extended version of a TESOL Blog post (here) that was published as a part of the TESOL Research Professional Council (RPC) Blog Series. You can find more blog posts from the RPC.

References

Acheson, K., Taylor, J., & Luna, K. (2016). The burnout spiral: The emotion labor of five rural U.S. foreign language teachers. The Modern Language Journal, 100(2), 522–537. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12333

Benesch, S. (2018). Emotions as agency: Feeling rules, emotion labor, and English language teachers’ decision-making. System, 79, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.03.015

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2013). Effective social and emotional learning programs.https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED581699.pdf

Gkonou, C., & Miller, E. R. (2021). An exploration of language teacher reflection, emotion labor, and emotional capital. TESOL Quarterly, 55(1), 134–155.https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.580

Hürriyet Daily News. (2020, November 20). Suicide rate increases in Turkey, report reveals.https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/suicide-rate-increases-in-turkey-report-reveals-160170

Pentón-Herrera, L. J. (2020). Social-emotional learning in TESOL: What, why, and how. Journal of English Learner Education, 10(1), 1–16.

Uştuk, Ö. (2022). ‘This made me feel honoured’: A participatory action research on using process drama in English language education with ethics of care. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 28(2), 279–294.https://doi.org/10.1080/13569783.2022.2106127

|

Download this article (PDF) |

Özgehan Uştuk is an EFL teacher, teacher educator, and researcher. He currently works at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University as a postdoctoral researcher. He has worked as an EFL teacher along with his research career in Turkey. His research areas include drama-in-education, TESOL teacher education, professional development, identity, and emotions. He has conducted several practitioner research projects in different forms, such as action research, exploratory practice, and lesson study.

| Next Article |

Academic English Instructor; Zhejiang University - International Campus, Haining, Zhejiang, China

Instructor; Program in Intensive English, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona, USA

To browse all of TESOL's job postings, check out the TESOL Career Center.

5 July 2023 (Deadline)

TESOL Board Expressions of Interest (EOI)

17 July 2023

ELT Leadership Management Certificate Program

31 July 2023

Supporting English Language Learners With Exceptional Needs

12 September 2023

School-Wide English Learning (SWEL) Workshop Series

TESOL

Worldwide Calendar of Events

Find conferences and events related to the field of English language education