|

You are a TESOL teacher. That likely means that you are fully

committed to offering the highest quality teaching to your students.

When you explain phrases like “she knocked it out of the park,” you want

to make the explanation and the learning memorable and fun. You are

totally focused on your students´ needs and always aiming to improve

your approach. When you get stuck, you reach out for resources or

advice. When you need ideas, you hop on the Internet to search for

inspirational exercises.

Your students are diverse, and you know culture plays an

important role in your classroom. You may have taken specific classes

dedicated to intercultural communication. More than likely, you have

used activities to help your students discover that what is “normal” for

them may look very different others’ ideas of normal. This stuff is

fun. It´s important and you love it.

But what about you?

Who is taking care of your needs? Your challenges? What about the personal hurdles you confront as you teach internationally or work

with a new group of students?

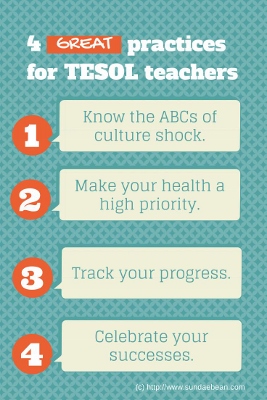

Today, I am going to share with you four things to make your

experience working across cultures more of an adventure and a more

enjoyable, richer learning experience—for you. If you

follow these steps, not only will it help you live well, it will

support you in being more productive, prevent immense amounts of lost

energy, and simply bring more joy into your life.

Sound good? Let´s get started.

Know the ABCs of Culture Shock

If you are like most people, when you think of culture shock

you think of that flash of disorientation and discomfort when you find

yourself smack dab in the middle of an unfamiliar cultural situation.

Oberg (1960), an anthropologist, was the first person to coin this term,

and his original association of it as a condition that could be

recovered from (the “medical” model) still persists today.

Culture shock essentially expresses an unmet need for

adaptation to a new cultural environment. People adapt to a new cultural

environment in a variety of ways, depending on their personality, prior

intercultural experiences, and exact circumstances.

You may have heard of the U-curve, originally proposed by

Lysgaard (1955), which illustrates a series of relatively predictable

phases migrants experience as they adapt to their new surroundings.

These phases include excitement, anticipation, shock and disorientation,

and eventually adaptation. More recently it has come to be accepted

that this U-curve repeats itself in more of a W-curve, accounting for

longer adaptation processes as well as reentry.

In an in-depth look at the shock of crossing cultures,

psychologists Ward, Bochner, and Furnham (2001) take these ideas even

further. Their research suggests that culture shock goes well beyond a U

or a W—but actually has more to do with the ABCs. Here is a closer

look:

A is for Affect: Basically understanding

“affect” is understanding your feelings. Next time you are in a new

cultural context and feeling confusion, anxiety, suspicion, or simply

the strong desire to be somewhere else, you might be experiencing the

affective aspect of culture shock. These negative feelings are often the expression of being in an unfamiliar environment.

B is for Behavior: When we are in a new

cultural context our typical behavior may not apply. This aspect of

culture shock becomes evident when we discover that our natural social

skills come across as awkward or inappropriate in a new context. Not

having the “right” behaviors in a new context may also hinder us from

achieving our personal or professional goals. It is no wonder that this

aspect causes stress.

C is for Cognition: This is quite clearly

the most complex and least straightforward aspect of culture shock.

Cognitive aspects of culture shock have much to do with how we see the

world, and how we see ourselves. When we are facing the cognitive aspect

of culture shock, we are confronted with identity development.

Simultaneously we are faced with cultural relativity and dealing with

ambiguity.

When you make a shift from seeing culture shock as a temporary

disorientation to seeing more of its complexity, you are better able to

“diagnose” what exactly is getting under your skin. What is more, you

are also well positioned to understand your next steps in relieving your

pain. If you are feeling awkward when meeting newcomers (shall I kiss,

bow, or shake hands?), then focus on better understanding local

behaviors. Are you brought down by anxiety? Give yourself some space to

work through these emotions. Feeling unsettled now that you are seen as

“White” rather than just an “American”? Understand this is a shift in

identity. Knowing more about the identity development process can help

you cope.

Make Your Health a High Priority

Working in an unfamiliar cultural context takes a toll on your

mind, body, and spirit. You can see this with the ABCs of culture shock.

Not an inch of your body is safe from its impact. Living and working

internationally is often like this: When it´s good, it is really good.

When it is bad, it feels really bad. During these times, it is hard to

maintain a healthy lifestyle—but critical that you do.

Let´s be honest: for many of us, living a healthy lifestyle is

hard enough in our own culture. Even so, your physical and mental

well-being plays an even more important role when you are outside of

your familiar surroundings.

Here is why:

- You cannot be in full service to your students when you are not well.

-

It is nearly impossible to have fun and enjoy the adventures

inherent to an intercultural context when you have low energy, are

slightly depressed, disoriented, or just on Facebook complaining to your

friends back home.

What you can do for your health right now:

- Plan your health into your week as seriously as you plan your lessons.

-

Commit to 30 minutes this week to your

health. You might decide to go to bed 30 minutes early, take a 30-minute

walk, or replace that after-work beer with a quick jog.

-

Mindfully invest an additional 30 minutes on a different day the following week.

-

At the end of each week, make note of how these extra 30 minutes impacted your day.

-

Keep going till you feel consistently healthy and strong.

Track Your Progress

We all know the now-cliché quotation “The journey of a thousand

miles begins with a single step.” While its wisdom holds true, do not

to overlook this important point: You cannot know that you have

journeyed a thousand miles unless you mark where you

started.

Take action now:

- Take note of where you are at this moment. Where do you

stand in terms of your foreign language skills, your social integration

into the community, your network of friends, and your knowledge of

cultural-specific behavior? Where are you in terms of the ABCs

above?

- Set a reminder in your calendar for every 6 weeks. Where are

you now? What have you gained? What have you learned? What is

better?

Do this for 1 year, and you will have pages upon pages of

evidence of your progress. An added bonus is that this will serve as a

useful reference for you in the future when you are applying for new

jobs, trying to mentor others, attempting to communicate what you have

learned, or just need a boost in your esteem.

Celebrate Your Successes!

What is the point of progress if you cannot celebrate it?

Mindfully make time to celebrate your big and little wins. Literally pop

out the champagne or take a moment to bask in the glory of having

gained the competency to order a meal in a new language. These things

feel good. And who doesn´t want to feel good more often?

By making these four steps truly mindful practices in your

exciting intercultural life, you will move forward with more ease,

energy, and optimism.

Now check in with yourself: Which one of these practices have

you been neglecting in your life? What do you think you will gain if you

start taking action in this direction today? Let me know here.

I am leaving you with a little present—it is a reminder for you

to post anywhere where you will see it regularly. Feel free to share it.

Commit today to dedicating yourself as fully to your own growth and learning as you do to your students’.

References

Lysgaard, S. (1955). Adjustment in a foreign society: Norwegian

Fulbright grantees visiting the United States. International

Social Science Bulletin, 7, 45–51.

Oberg, K. (1960). Culture shock: Adjustment to new cultural

environments. Practical Anthropology, 7,

177–182.

Ward, C. A., Bochner, S., & Furnham, A. (2001). The psychology of culture shock. New York, NY:

Routledge.

Sundae Schneider-Bean earned an MA in intercultural

communication at Arizona State University in 2006. She is an

intercultural specialist and coach who currently lives in Burkina Faso

(West Africa). You can find out more about her at http://www.sundaebean.com

or read her blog;

sign up for her newsletter here. |