|

The term deixis is derived from the Greek

word pointing at or denoting a referent in the circumstances of

utterance. First of all, the referents can be demonstratives, personal

pronouns, tense, specific time and place adverbs, and a variety of

grammatical features. The referents represent a prototypical or focal

exemplar to indicate a person (person deixis), time (temporal deixis),

space (spatial deixis), social ranks (social deixis), or what has been

just stated (discourse deixis). For example, when a speaker says, "Meet

me there in a week from now with a banner. That is what I needed to draw

my attention last time I visited Singapore,” the word me indicates person deixis; here indicates

spatial deixis; (a week from) now indicates temporal

deixis, and that indicates discourse deixis. Second,

to understand what each word that I have previously mentioned means, the

circumstances of utterance need to be investigated. The circumstances

of utterance have two sides: the side of emergent situational

context and prior context (Kecskes,

2014). For instance, in the emergent situational

context, me can accurately point at Mr. David, the

speaker who has made the utterance. The word there refers to Changi airport. A week from now only makes sense if the interlocutors are both aware that at

the point of speaking, it is June 1, 2019, so both can infer that they

will meet each other again on June 8, 2019. In contrast, to understand

what that indicates, not only does a hearer need to

know the action of holding a big noticeable banner previously mentioned

in the emergent situational context, but he also has to remember and

relate to the size of the banner used last time to welcome Mr. David. In

other words, while emergent situational context represents the physical

interactional environment where the conversation takes place, the prior

context represents the privately mental and psychological storage of

interactional occasions of an individual. Because of the considerable

reliance on contextual inference, deixis, therefore, has been widely

studied to comprehend different strategies of how speakers layout their

specific referents and hearers interpret contextual cues to allocate

speaker’s intended referents (Fauconnier, 1985; Kiesling, 2005; Kiesling

& Jaffe, 2009; Mei, 2002; Silverstein, 2006).

One the one hand, although

there are many studies about deixis (e.g., see Hanks, 2005; Enfield,

2003 for a review), most of them investigate the phenomenon within a

homogeneous context of use. On the other hand, Hanks (2011) pointed out

that deixis reflects the encyclopedic knowledge that is set up and

anchored locally and culturally according to sociopsychological grounds

of the language users. This characteristic of deixis motivated me to

examine deictic usage in a heterogeneous context, where localism of each

speaker’s deictic usage influences their deictic decoding and encoding

messages. In the case of intercultural communication, where speakers

coming from other sociocultural backgrounds use English as a lingua

franca, I assume that the use of deixis in English is intrinsically

different from intracultural communication. The reason is that the prior

contexts of those speakers are more diverse pertaining to the norms of

using language than those of intracultural communicators. Intercultural

communicators cannot hold the assumption that they share pre-established

communal norms of reference and pre-existing formulas and frames, or a

shared common ground. The intercultural interlocutors exert more

individual abilities to decode each other’s deictic usage, especially if

that deictic referent is deeply rooted in sociocultural-specific prior

context. For example, take a look at the interactional excerpt taken

from the study’s corpus:

American Female: It was a brunch that you had to wear pink when attending.

Korean Female: ...It’s like they required you to wear a color..?

American Male: Was it a girl, is that why they said pink?

American Female: Yes, yes.

In the dialog above, everyone is using the discourse deixis it and elaborating more information to clarify its

referential event of a baby shower in their mind. The thing that matters

is only the American speakers (American Female and American Male) are

familiar with the mental image of the target referent due to their own

experience in their native culture. Therefore, the American Male could

add additional detail to decode the referential meaning without much

effort. In contrast, the Korean Female, who was not aware of the

sociocultural meaning the other speakers are referring to, was mainly

building up her concept around “it.” Hence, she asked for confirmation

and clarification from American Female instead of indicating she could

retrieve the mental frame of the referent.

The findings of this pilot study (the study belongs to an

ongoing broader-scale project) discussed in this article confirmed that

the use of deixis in intercultural communication deviates significantly

from its norms in intracultural communication carried out among English

native speakers. Specifically, the influence of L1, the sociocultural

backgrounds of L1, and the pragmatic intake from L2 socialization may

determine their use of deixis to build mutual understanding among

advanced-level second language speakers in intercultural communication.

Hence, the aforementioned factors need to be taken into consideration to

uncover the different and appropriate communicative strategies employed

by intercultural communicators.

The corpus consisted of six 1-hour transcripts of the

conversation carried out by three groups of participants at one of the

U.S. universities located in the northeast of the country. Thirteen

subjects were involved in this study, including four native-speaking

(NS) and nine nonnative-speaking (NNS) students (both male and female).

The Intracultural Group consisted of four American native speakers who

were all from the same town near the university and had no experience in

traveling out of the United States or using a second language. They

fall closer to the intracultural end of the comparative continuum. The

Intercultural Group has five subjects with different first languages and

cultures that have very little or nothing in common (China, Nigeria,

USA, Brazil, Russia). They fall closer to the inter-cultural end of the

comparative continuum. Between Intercultural Group 1 and 2,

Intra-Intercultural Group was created. This represented the

intercultural communication context where interlocutors maintain similar

backgrounds from the intracultural group yet still deviate from each

other if coming to sociocultural specificity. I included participants

from China, Singapore, and Vietnam in this group since countries in the

(South East) Asian regions construct their cultural ideologies and

sociocultural conceptualization on the doctrines of Confucianism

(Wei-Ming, 1996).

The group met three times throughout one semester for a topic

related to different cultures around the world. The three topics

included "cultural patterns and prejudices," "cultural belonging,

customs and beliefs," and "cultural heritage." The subjects discussed

freely in English on the proposed topic, and the researcher only

interfered when the discussion paused longer than three minutes before

sixty minutes ran out. The researcher provided some prompts such as,

"What do you all think about…? In your country, what are some cultural

beliefs towards gender roles?" After transcribing all sessions analyzed

in this study, the occurrences of each deixis were identified and

categorized into types of deixis. There were only four types of deixis

found in the corpus, including person deixis, temporal deixis, spatial

deixis, and discourse deixis.

Preliminary Findings

The Percentage of Deixis Use in Each Group

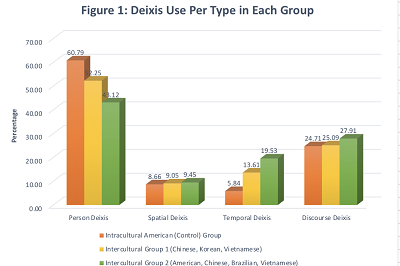

Figure 1 provided the percentage of each type of deixis the

communicators of each group utilized during their communication (the

total number of words in each group is standardized before calculating

the deixis proportion so that the percentage can be comparable across

the groups).

Figure 1. Percentage of deixis found in each group of speakers.

|

Orange: Intracultural Group

Yellow: Intra-Intercultural Group

Green: Intercultural Group |

As shown in Figure 1, the overall trend is that person deixis

is used most in the discussion, denoting the stance of the speaker, the

relation to the hearer(s) and the people emerging in the talk. The

spatial deixis, temporal deixis, and discourse deixis are used with less

proportion compared with person deixis, to add more details and

information to the discussed subject(s) in the talk. Notably, the

proportion for each type of deixis varies among the groups. First of

all, the Intracultural Group with American speakers 60.79% of deixis

used in the corpus accounts for person deixis, followed by discourse

deixis (24.71%), spatial deixis (8.66%) and temporal deixis (only

5.84%). The proportion in person deixis found in this Intracultural

group is higher than the other two groups; whereas, for other types of

deixis, it has the least proportion. To be specific, person deixis

gradually decreases in Intracultural Group (52.25%) and Intercultural

Group (43.12%). Next comes discourse deixis. The use of discourse deixis

increases by 0.38% in Intra-Intercultural Group and by 3.2% in the

Intercultural Group compared with Intracultural Group. Similarly,

compared with Intracultural Group, temporal deixis is used more in

Intra-Intercultural Group (13.61%) and in Intercultural Group (19.53%).

Spatial deixis is also used more in Intra-Intercultural Group and

Intercultural Group (9.05% and 9.45% respectively). The graphic analysis

indicates that while speakers coming from a relatively definable and

similar sociocultural backgrounds tend to withhold and save more

detailed information on the discussed subjects in the talk, speakers

coming from more and more diverse sociocultural contexts tend to

elaborate on specific facts and circumstances detailed on time,

space/location, and surrounding subjects.

Deixis Usage as a Strategy in Meaning-Making in Intercultural Communication

Content analysis reveals the reason why deixis is used quite

differently in intercultural communication compared with intracultural

communication. First of all, although English is used to communicate as a

lingua franca to communicate with each other, deictic usage of speakers

whose first language is not English is affected by the mental world of

their L1. For instance, in the corpus, the speakers coming from Asian

cultures, under the impact of Confucianism, preferred to use more person

deixis "we" instead of "I" to show the inclusion of both addressers and

addresses in the talk. They also used “we” to establish a harmonious

relationship with other interlocutors.

Also, if the hearers are from different sociocultural

backgrounds, it is challenging to navigate the referential meaning of

the deixis. However, with the presence of deictic words, at least there

are some contextual clues for everyone to follow the story. Consider the

excerpts below. The discourse deixis is highlighted in green. They

present themselves all over the discourse to assist the interlocutors to

build the concept of newborn babies’ celebration and naming ceremony,

which vary across cultures:

Excerpt 1 (Intra Intercultural Group discussing the customs related to celebrating newborn babies)

Chinese Female: So, in China, like other people in general,

whether like friends, relatives…it’s like they will give like red

envelopes with money to the baby. That not only like just for the baby,

but it’s like...blessing in general.

Taiwan Male: We do that in our culture as well. And also it’s a big celebration when the baby is… one?

Chinese Female: Not too much when the baby is one. Full moon… a month is better.

Excerpt 2 (Intercultural Group discussing the beliefs related to naming babies)

Brazilian Male: Usually the name is chosen by the parents. That I don’t know if there’s any formal ceremony.

Chinese Female: In China, that goes down with the, uh, father’s side,

like your father and father's brothers, will share like one character,

and like you, and if you are a son, and you and your brothers will share

like one character that is representing a generation, but that’s only

for the father’s side. Like, the paternal names, not like for females.

American Male: Oh…That we will have expensive gifts to guess

and announce the name. That’s usually left for the parents of the

parents, the grandparents as an honored duty. Yeah.

Deixis of spatial and temporal is used more excessively as

well as a strategy for meaning-making in intercultural communication

groups (Intra-Intercultural Group and Intercultural Group). The more

diverse the group of speakers is, the less common they share regarding

their private prior contexts. Because the speakers in intercultural

communication do not have a common ground, they have an urge to build as

solid (even though it is temporary) common ground as possible to make

the conversation smoother and more cohesive. Interestingly, when the

communicative contexts move further away from intracultural contexts,

the interlocutors take more advantage of deictic words to construct new

referential concepts with information obtained from the speakers. In

other words, to help the hearers understand what the speaker is

referring to, the speaker chooses to recruit more deictic words to

describe the referential entities and their context of use in great

details. That is the reason why more spatial, temporal, and discourse

deixis were found in the corpus, which is not the case in Intracultural

Group. In intracultural communication, fewer deictic words were detected

or repeated because speakers could relate to the referents. Instead of

focusing on expanding the descriptive, contextual information and

bringing their mental frame to life, speakers coming from the same

sociocultural backgrounds concentrate on giving comments and egocentric

perspectives on the topic. They use more person deixis to offer their

own opinions and subjective elaborations on the discussed

topic.

Excerpt 3 (Intracultural Group talking about welcoming the newborn babies)

American Female 2: That’s an hour clapping, like, I would like a

small announcement about our new family member. I don’t feel like

wasting everybody’s time. I feel like that takes away the anxiety time

from like letting people show up and chat by themselves.

American Female 3: Yeah.

American Female 2: Like, “yay, I am not familiar with the

relatives of the baby!” Like, nobody's excited about the baby. More

about social chit-chat.

Conclusion

Communicative context includes language users—utterer/speaker

and interpreter/hearer, the mental world, the social world, and the

physical world. The observation of deixis usage in intercultural

communication in this pilot study indicates the distinctive difference

where the primary attention is drawn on building new concepts and common

ground among interlocutors rather than assuming everyone is familiar

with the discussed subject. The study hints at pedagogical implications

in the area of teaching pragmatic skills for second/foreign language

learners. First of all, ESL/EFL teachers could be aware of aspects of

physical, social, and mental reality that are activated by the utterer

and the interpreter in their respective choice-making practices due to

their sociocultural background. Second, deictic words can be actively

and consciously employed and taught as a highly flexible strategy to

negotiate meaning and satisfy communicative needs.

References

Enfield, N. J. (2003). The definition of what-d'you-call-it:

semantics and pragmatics of recognitional deixis. Journal of

Pragmatics, 35(1), 101–117.

Fauconnier, G. (1985). Mental spaces. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hanks, W. F. (2005). Fieldwork on deixis. Journal of

Pragmatics, 41(1), 10-24.

Hanks, W. F. (2011). Deixis and indexicality. Foundations of Pragmatics, 1,

315.

Kecskes, I. (2014). Intercultural pragmatics. USA: Oxford University Press.

Kiesling, S. F. (2005). Norms of sociocultural meaning in

language: Indexicality, stance, and cultural models. Intercultural discourse and communication: The essential

readings, 92–104.

Kiesling, S., & Jaffe, A. (2009). Sociolinguistic perspectives on stance. OUP USA.

Mei, L. W. S. (2002). Contextualizing intercultural

communication and sociopragmatic choices. Multilingua, 21(1),

79–100.

Silverstein, M. (2006).

Pragmatic indexing. In K. Brown (Ed.) Encyclopedia of language

and linguistics (2nd ed., Vol. 6, pp. 14–17). Amsterdam, the

Netherlands: Elsevier.

Wei-Ming, T. (1996). Confucian traditions in East Asian

modernity. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and

Sciences, 12–39.

Hanh Dinh earned a master’s degree in TESOL and is

currently a doctoral student in curriculum and instruction at SUNY at

Albany. Her research interests include intercultural communication,

pragmatics, and bilingualism. |