|

After years of watching students struggle with spelling, I

began to record which of my students were having difficulty spelling

along with the words that were the most problematic for them. The first

thing I noticed was that it was not only the low readers who experienced

spelling woes; just as many of my voracious readers also struggled. In

the process I discovered that many of these students were continuing to

make the same mistakes no matter how many times I highlighted and

corrected their papers. I wanted them to take more responsibility for

their learning. In order to do so, I realized that I had to directly

teach students how to stop and think about their work as well as support

them by providing constant reminders. Once they stopped to check their

work, they also needed to have specific strategies to help them recall

the correct spelling. Therefore, I began examining ways to help students

become better spellers. Knowing that brains are dynamic and thrive on

novelty, I developed four artful cognitive strategies that use multiple

learning styles to build better spellers.

“MISSISSISSIPPI”―DOES THAT LOOK RIGHT?

It is well known that English spelling is difficult even for

native speakers. For some students, writing spelling words five times,

grouping them into families, or sounding them works well. However,

countless others need something more. Often these are the students who

run on auto-pilot, never stopping to think about spelling. Or they may

know the word is spelled wrong but don’t have a way to help them recall

how to write it correctly. In time, tuning out can become the typical

response when they don’t know how to do something; they get stuck,

negative emotions and anxiety increase, and they shut down.

Students who struggle think that the “smart” kids are just born

smart; answers just “pop into their heads” naturally without effort. It

is true that recalling information is easier for some than others. It

may appear that their friends’ knowledge is more effortless as the

friends look up and then immediately after write down answers. However,

the real difference is that the “smart” kids use strategies. Those for

whom metacognitive strategies do not come naturally look up or stare out

and wait for the answer to pop into their heads. The difference is one

group is intrinsically better able to employ strategies than the other.

Teaching content is only a small percentage of what we do. The

larger and more important task is to set students up to be life-long

learners who take ownership of their learning. To make this occur,

students need to be directly taught metacognitive strategies. Metacognitive refers to strategies used for

- Planning for learning: Deciding how to focus attention, knowing how you learn best, etc. Am I ready to learn?

- Thinking about the learning process while it is happening: What can I do to help me remember?

- Self-monitoring of comprehension/production: Is it making sense to me?

- Evaluating learning afterward: Did my strategy work?

By doing so, students learn how to build and use their

metacognition, so they create their own meaningful, relevant strategies

to help them recall information and become independent learners.

SHOW THEM HOW TO

- Stop…

- Think about a strategy…

- Apply!

I have developed teaching techniques that address various

learning styles. These are to be used as scaffolds until correct

spelling becomes internalized. Because the brain is dynamic and thrives

on patterns and novelty, the process of creating strategies can get

students excited, which lowers the affective filter so there is less

chance of them shutting down as a result of frustration or anxiety.

Taking spelling into this realm helps students realize they can learn

how to spell and have fun doing it.

PICTURE IT!!

This technique entails drawing or making a mental picture that

is associated with the word. Sometimes these work in conjunction with

the word’s meaning; other times it is a “silly” or novel reference.

Students form them via teacher modeling as well as connect them to prior

knowledge.

minute common misspelling: menit, minet, etc.

HabitBreaker: text message: “C u in 6”

This helps students remember that u and in are in the word minute. In

addition, the number 6 provides a way for students to recall that there

are six letters in the word and not five.

office common misspelling: ofis or offis

HabitBreaker: Draw/make mental picture of

ice skating and falling down. Think how you had to get off the ice and go to the office

This idea came from a student who went ice skating for the

first time. I suggested she imagine someone was skating and fell. This

person had to get off the ice and go to the office to call home, get an

ice pack―whatever makes a connection for the student. She drew a picture

and highlighted off and ice. She

not only got it right on her spelling test, but hasn’t misspelled it in

her writing to date. It is very satisfying to see a student stop, think,

and apply.

recital common misspelling: risatel or resital

HabitBreaker: “Don’t rec it Al“

We pretend Al is having a music recital at school. We send him a

text message before the make-believe show telling him not to mess it up

or wreck it. We try to apply our friend Al to as many words that end inal as possible. If we group them using Al, students

are better able to differentiate between similar endings such as el and le.

SAY IT!!

This technique involves using oral phrasing to help recall

spelling. Here are a few examples of some words that are commonly

misspelled in students’ work:

went common misspelling: wint or whent

HabitBreaker: “We went on Wednesday”

this common misspelling: thes

HabitBreaker: “This is good!”

some common misspelling: sum

HabitBreaker: “So give me some!”

Usually these are based on simple words that students can

spell (so, me, we, he, is, an, on, in, etc.) so it is

easy to connect with patterns and words they already know and are

comfortable spelling.

CHARACTER-IZE IT!

This technique helps students differentiate between difficult

word endings by making characters out of them. Below are two characters

we have used in class: Ant and Ed.

Ant is a character students enjoy. Depending on the dialect

used where one lives, the difference between -ant and -ent at the end of

a word is difficult to distinguish orally; often there is no notable

difference at all. Therefore matching words with a character helps

students group them in a way that makes it easier to recall the correct

spelling.

defendant common misspelling: defendent or defendint

HabitBreaker: draw a

defendant―an ant that defends others;

ignorant common misspelling: ignorent or ignorint

HabitBreaker: draw

ignorant―the ant that ignores, that doesn’t pay attention or remember

There is also Ed for various past tense conjugations. These can

also help with basic misspelling. Students draw a picture or go online

to create Ed and use him as a basis of their strategy.

abandoned common misspelling: abandonet, abandit, or ubandid

HabitBreaker: “There was a band on Ed.”

presented common misspelling: presentid or prasentad

HabitBreaker: “Pre sent Ed a letter” or

“Pre presented a letter to Ed.”

Students like making up clever examples for Ant and Ed as

well as Al! Many possibilities exist for both teachers and students to

explore.

MORPH-IT!!

Morphing is using a word that a student already knows and

morphing it into target word. Many cartoons involve aliens and machines

transforming or morphing. Students are fascinated with how their

spelling words can morph like a secret code. Sometimes a phrase can be

added to help cement the idea.

stuck

HabitBreaker: luck => tuck => stuck

“What luck, I tuck and got stuck!”

In creating this example, the student knew how to spell luck, so I changed the l into a t and then added s. We live in a

state that experiences the occasional tornado. Therefore we practice tuck and duck. If these words are

not already in students’ vocabulary, then adding them is a good idea.

Here are a couple more examples. Again they began with words

the student knew and morphed into the target word.

pocket

HabitBreaker: lock => locket => Pocket

“I lock my pocket with a locket.”

paint

HabitBreaker: paint rain => pain => paint

“It’s a pain to paint in the rain.”

MOVE IT!!

This technique involves physically moving letters to form words and/or using body movements.

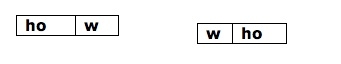

who vs. how commonly confused

HabitBreaker: Write and/or cut out ho and w. Put the w in front of ho to spell who. Then move the w to the end to

make how and repeat. For reinforcement say, “Who

knows how to spell who?”

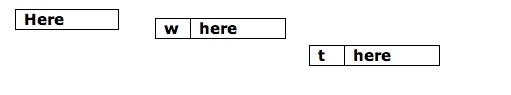

here, there, where? commonly confused with homophones; hear, their/they’re, were/wear

Habitbreaker: Write and/or cut here, t, and w.

Again move them around to spell “Where? Here? There?” You can add more

movement by asking “Where?” then removing w and

pushing here closer to you. In turn, you can add t to form there, which you can

push away. Not only do all three words share the base word here, but they are also related to placement, which

further supports the strategy.

Most of these techniques are used in combination. This is

the best approach because it aids in better reinforcement and recall.

CONCLUSION

In the process, students build more than just their metacognitive knowledge and improved spelling. They also

- are exposed to new vocabulary and higher-level syntax

- build on and improve reading strategies: chunking, rhyming, root words

- increase ability to see/awareness of patterns

- correct mispronunciation

- develop abstract thinking

Through accessing these techniques, students are active and

have a plan for their own learning. We don’t want students to surrender

to the idea of working on autopilot and winging it, in hopes of

succeeding. Students can take possession of their learning by making and

using their own meaningful and relevant strategies to learn new

information. This is key to creating independent, confident, competent,

and happy life-long learners.

REFERENCE

Brown, H. D. (2007). Principles of language learning

and teaching (5th ed.). New York: Pearson Education.

Gelene Strecker-Sayer,strecker-sayergelene@rockwood.k12.mo.us,

is a national board-certified teacher and Fulbright Scholar who has

presented at the state and national levels on various topics such as

pull-out ESOL programs, standards-based curriculum writing,

international adoptees and their language learning, school

collaboration, and the correction of common grammatical misuses of

English. Currently she teaches K-12 ESOL students for Rockwood Public

Schools in St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Editor’s Note: To receive samples of 40

words/HabitBreaker kinesthetic letters and/or spelling cards, please

contact the author at the e-mail listed above. |