|

Action research, also referred to as teacher research, teacher

reflection, or practitioner research (Pappas & Raymond-Tucker,

2011), is the recursive process of teachers identifying a problem,

introducing solutions, and documenting and reflecting upon the results

(Bailey, 2001). It is argued that engaging in action research increases

instructors’ awareness of their teaching practice (Atay, 2007) and

encourages “reflective, data-driven instruction” (Pappas &

Raymond-Tucker, 2011, p. 4). For me, the decision to engage in action

research emerged from identifying a knowledge deficit in both my

understanding of written feedback pedagogy and my own feedback

practices. Therefore, the goal of action research was to analyze the

written feedback I gave students in order to understand my feedback

practice more fully and compare it more accurately to expert views of

best feedback practice. The questions that guided my research were: How

do I comment on student writing? How do my findings compare to expert

research? Which feedback practices should be continued and which should

be changed? Because action research is a recursive endeavor, I repeated

the study a year later to understand if I had indeed changed my feedback

practice. In this report, I present the research methodology, results,

reflections, and resulting actions of both studies.

RESEARCH DESIGN

To examine my feedback on student writing, I selected a small

subset of papers on which I had provided feedback during my first year

teaching a university-level reading and writing course. This was an

intermediate-level course for matriculated students at a large

Midwestern university. In total, 18 papers were selected, which

comprised nine sets of first and final drafts—three sets of papers from

three similar assignments. All nine sets received final grades between

75 and 85 percent. This grade range was chosen because the median and

mode score of each assignment fell into this grade range; I therefore

considered these papers to be representative of the average paper. As

teacher-researchers are advised by Richards and Lockhart (1996) to start

with small research projects, I used this limited grade range as one

way to reduce the scope of the research project. In addition, I examined

only papers for which I had both the first and final drafts.

After compiling the papers to be analyzed, I then conducted a

preliminary analysis of the comments I made in order to inductively

select relevant categories to research (see Connors & Lunsford,

1993; Reid, 1990). The relevant categories that emerged from this

process related to grammatical style (questions, statements, or

commands); content (organization, content, vocabulary, meaning

clarification, grammar, or praise); and error identification method

(whether or not grammar errors were pointed out or corrected). I also

noted which comments were made with a mitigation strategy (see

definition and discussion below). The final step was to analyze every

comment on all 18 papers according to these categories. For each comment

I recorded which categories applied to that comment so the content of

both the comments and categories could be examined in order to

understand features of my feedback.

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

After determining the categories and features of each comment

and compiling the frequency of each comment type, I analyzed these

findings according to second language writing research and

teacher-training resources; I also reflected on the data in relation to

my own teaching goals and teaching context. This process highlighted

both positive and negative features of my feedback.

Positive features included the comment variety and quantity.

Ferris and Hedgcock (2005) encouraged instructors to provide holistic

feedback rather than limiting feedback to just one issue. The fact that

each category examined in the study accounted for between 11 and 26

percent of the total comments shows that I did not greatly favor one

issue but instead gave feedback on various components of writing

including grammar, organization, content, and vocabulary. Another

positive feature found in the analysis was the number of comments. I

averaged 15 comments on each paper, which is similar to the number of

comments given by other teachers (see Ferris, Pezone, Tade, &

Tinti, 1997; Treglia, 2008). Apart from being similar in quantity to

other instructors’ feedback, the amount seemed appropriate for this

teaching context. Fifteen comments on papers of 450 to 800 words seemed

like an amount that could provide revision guidance and writing

instruction to the intermediate students but would not be too

overwhelming. In sum, I felt positive about the variety of issues

addressed and the quantity of comments and planned to continue these

features of my feedback.

Other results, namely the errors on which I focused and the

manner of dealing with grammatical errors, warranted change. Multiple

authors argue that correcting mistakes does not improve students’

grammatical competence; instead they advocate using other methods that

communicate the existence of an error without providing a correction

(Ferris, 2006; Lalande, 1982). Methods of doing this include

underlining, highlighting, or using a code (e.g., v.t. for verb tense

error). My research revealed that I corrected 66 percent of grammatical

errors. I therefore determined to discontinue this practice in favor of

pointing out the errors with a code that denoted the type of grammatical

error without providing the correct answer.

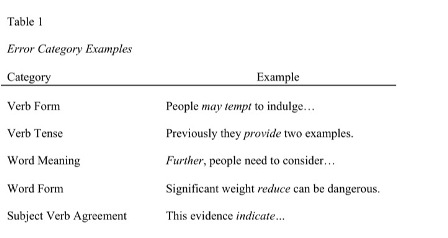

In addition to changing my manner of dealing with grammatical

errors, another concern was the types of grammatical errors on which I

focused. The research results revealed that approximately 15 percent of

my grammar comments focused on prepositions and articles. Although 15

percent may not be a large percentage, for intermediate students, who

are still making errors that impede meaning comprehension, article and

preposition mistakes, which rarely affect meaning, should not be a

focus. Instead, using the findings and advice of Ferris (2006) to focus

error treatment on a small set of grammatical forms and Hinkel (2004) to

focus on errors that content professors find egregious, I now focus on

five types of grammatical errors: word form, word meaning, verb tense,

subject-verb agreement, and word order. Examples of each error can be

seen in Table 1.

Each of these errors is marked with a code that is explained to

the students. For example, a word form error is marked “w.f.” Most

important, I now focus on these errors in class throughout the semester

so that the students not only see these errors on their papers but also

learn about why these errors are important, how to find them while

editing, and how to correct them.

The third change involved adjusting my use of mitigated

critiques. Mitigation is frequently used in written feedback in many

U.S. educational contexts to curb students’ negative reactions to

criticism. Mitigated feedback often includes pairing criticism with

praise (e.g., This is good information, but you could explain it more)

or pairing a criticism with a suggestion (e.g., The topic sentence is

not clear. Since the paragraph is about cultural change, you could start

the paragraph by introducing and defining it), and using questions

instead of direct criticism (e.g., Can you say this more directly?).

Although both praise and critiques (any form of negative feedback) can

be mitigated, in my research I focused on the mitigation of critiques.

Hyland and Hyland (2001) found that mitigated comments, which are often

grammatically and pragmatically difficult, frequently confuse low-level

university English language learners. However, Treglia (2008) found that

both native and nonnative intermediate-level university students felt

mitigation was a valuable way to reduce the sting of criticism. Key

differences in the amount of mitigation—teachers in Hyland and Hyland’s

study mitigated just over 75 percent of criticisms whereas in Treglia’s

study the teachers used mitigation strategies in just 17 percent of

criticisms—and the students’ ability level in each study may account for

the divergent findings. For instructors, these findings can be

reconciled by viewing mitigation as a valuable yet potentially confusing

form of feedback, especially for low-level students.

From these results, I developed a heuristic to guide when and

how much to utilize mitigation strategies: Mitigation should not be used

for highly important comments. What is “highly important” will, of

course, vary based on the teaching context but may include issues of

plagiarism, thesis statements, or topic sentences. One way I define

“highly important” is by thinking about how I will grade the final

draft. If a student, for example, would receive a significant grade

reduction for failing to understand that he plagiarized part of the

paper, mitigation should not be used. A student may not be able to

interpret a comment such as “Are some parts of this paragraph copied

from an online source?” to mean that the teacher knows that part of the

paragraph was copied and that the student should paraphrase or use

quotations on the final draft. Instead, a more direct comment such as

this should be used: “Part of this paragraph is copied from an online

source. Copying directly from a source is not permitted; please

paraphrase these ideas as we learned in class last week.” However, for

other issues that are less important, mitigation could be used. Some of

these less important issues may include adding examples, further

explanation, or colorful description. For example, if an idea is pretty

clear but would be even better with more description, an appropriate

comment may be “This is a really interesting idea. However, a bit more

explanation would be useful.” This style of commenting should reduce

potential confusion regarding important issues, but will allow for some

mitigation to be used because students seem to appreciate this style of

comments.

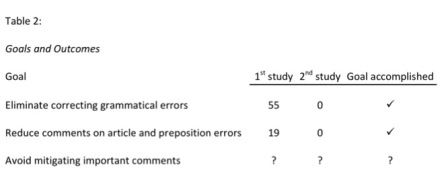

STUDY REPLICATION

After a year, I replicated the study to determine if I had

enacted these proposed changes. Table 2 shows that I did accomplish some

of my goals.

I no longer corrected grammatical errors or commented on

articles and prepositions and I reduced mitigation use. One caveat is

that, although I did mitigate fewer critiques (39% instead of 69.5%), it

was difficult to determine if I used mitigation only on very important

issues. I had some ideas about how this heuristic applied to my teaching

situation as explained above, but I still found it difficult to analyze

that heuristic in a way that was consistent. When I retrospectively

analyzed my comments, it was difficult to take into account all the

aspects of the decision to use mitigation and systematically determine

which comments addressed very important issues. This second study

reveals that continual refinement of my understanding and use of

mitigation is needed. As I have continued to review my research

findings, monitor my ongoing feedback practice, and read other research

studies, I have also begun to realize that potentially not all

mitigation strategies are equally confusing. Providing a suggestion may

not cause the same confusion as making a critique in the form of a

question. Therefore I need to research and understand the effects of

mitigation strategies separately as I continue to refine my use and

understanding of mitigated comments.

CONCLUSION

The benefits of this research have been my improved understanding of writing feedback literature, the confidence I have in my work, and the hopefully increased clarity of my comments. Despite

these benefits, the study was not without limitations and difficulties.

Some of the specific difficulties included establishing relevant

categories for investigation, defining comment category completely, and

consistently applying the definitions. As a novice researcher, I felt

overwhelmed at times. Limitations included the fact that the actual data

is not widely generalizable because of the small data set. However,

given the classroom focus of this research, sound research methodology

and generalizability were goals, but not the ultimate goals; the

ultimate goals were to gain understanding of my feedback practices,

acknowledge and question my assumptions, and engage fully in my teaching

practice. For instructors thinking about embarking on an action

research voyage, one way to have an even richer experience while also

mitigating some of these difficulties is to research collaboratively

(Allwright, 2005). This enables deeper and more thorough discussions

about methodology, results, and analysis. Although researching alone or

collaboratively is not easy, it is worth the effort. The heart of

teacher research is that it fosters learning—a process of “knowing and

experimenting, reflection and change” (Reid, 1993, p. 257). It is in

this process that great personal and professional reward is found.

AUTHOR NOTE

This article is adapted from a longer version published in TESOL Journal. See: Best, K. (2011). Transformation

through research-based reflection: A self-study of written feedback

practice. TESOL Journal 2(4), 492-509. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5054/tj.2010.271901

REFERENCES

Allwright, D. (2005). Developing principles for practitioner

research: The case for exploratory practice. Modern Language

Journal, 89, 353–366.

doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2005.00310.x

Atay, D. (2007). Teacher research for professional development.ELT Journal, 62, 139-147.

doi:10.1093/elt/ccl053

Bailey, K. (2001). Action research, teacher research, and

classroom research in language teaching. In M. Celce-Murcia

(Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign

language (3rd ed., pp. 489–498). Boston, MA: Heinle &

Heinle.

Connors, R. J., & Lunsford, A. A. (1993). Teachers’

rhetorical comments on students’ papers. College Composition

and Communication, 44, 200-223.

Ferris, D. (2006). Does error feedback help student writers?

New evidence on the short and long-term effects of written error

correction. In K. Hyland & F. Hyland (Eds.), Feedback

in second language writing: Contexts and issues (pp. 81-104).

New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Ferris, D. R., & Hedgcock, J. S. (2005). Teaching ESL composition: Purpose, process, and

practice (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ferris, D. R., Pezone, S., Tade, C. R., & Tinti, S.

(1997). Teacher commentary on student writing: Descriptions and

implication. Journal of Second Language Writing, 6), 155-182.

Hinkel, E. (2004). Teaching academic ESL writing:

Practical techniques in vocabulary and grammar. Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hyland, F., & Hyland, K. (2001). Sugaring the pill:

Praise and criticism in written feedback. Journal of Second

Language Writing, 10, 185-212.

Lalande, J. (1982). Reducing composition errors: An experiment.The Modern Language Journal, 66,

140-149.

Pappas, C. C., & Raymond-Tucker, E. (2011). Becoming a teacher researcher in literacy teaching and

learning: Strategies and tools for the inquiry process. New

York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Reid, J. (1990). The dirty laundry of ESL survey research. TESOL Quarterly, 24,

323.

Reid, J. (1993). Teaching ESL writing. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Richards, J. C., & Lockhart, C. (1996). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Treglia, M. (2008). Feedback on feedback: Exploring student

responses to teachers’ written commentary. Journal of Basic

Writing, 27, 105-137.

Karen Best teaches English as a second language at the

University of Wisconsin-Madison. She holds an MA in applied English

linguistics from the same institution. Her research interests include

writing feedback, student views of feedback, and teacher action

research. |