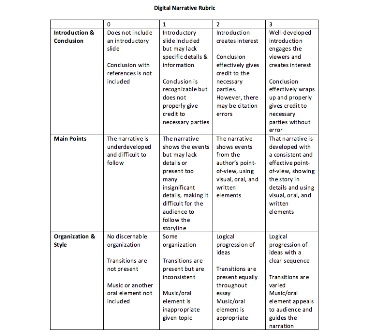

|

Many universities offer first-year writing courses designed

specifically for English language learners. The purpose of these courses

is to offer students additional academic support and greater

individualized writing instruction. Yet Matsuda (2006) has expressed

concern with such courses, as often language diversity is not recognized

or valued. Placing English language learners in first-year writing

courses with domestic students helps celebrate diversity, while still

improving students’ writing skills and offering them valuable

personalized instruction. In fall 2009 and 2010, I taught a section of

first-year writing designed for English language learners and domestic

students. The English language learners enrolled in this course were

international students who had been at the university for only a short

time. Most spent at least one semester in the university’s IEP before

advancing to their undergraduate programs. The domestic students were in

their first semester of study.

Aware of the challenge Matsuda presented, I strived to

recognize and celebrate the rich diversity represented in the class. One

way was to encourage students to use multiple linguistic codes in their

assignments, specifically in their multimodal compositions―texts that

stray from the printed word or alphabet and include features such as

animation, sound, and music (Tulley, 2009). A specific multimodal

assignment I designed for this course was a digital narrative (see

appendix). For this assignment, students transposed a written narrative

about a memorable childhood event into a video using either MovieMaker

or iMovie. Rather than solely depending on the written word, students

were encouraged to use visual images, sound, and animation to tell their

stories. I began the unit with a tutorial on how to use MovieMaker (we

met in a PC computer lab) and then encouraged students to visit the Student

Technology Center on campus if they needed further

assistance.

Many students already knew how to use the computer software and

served as tutors, helping other students with their projects. Because

the class met in a computer lab, I also assisted students with any

technical difficulties they experienced.

Overall, the technology helped create a collaborative

atmosphere, build class rapport, and provide students with a platform to

share their cultures. In addition, because digital narratives required

students to use photographs and music, along with some written text, the

English language learners could bring their native languages into their

work by combining or blending languages through different types of

text. This strategy is called code meshing.

WHAT IS CODE MESHING AND HOW IS IT USED?

Code meshing calls for students to apply their language skills

in a sophisticated rhetorical style in order to best communicate with an

audience. According to Canagarajah (2006), when code meshing, “It is

not even sufficient to learn different English varieties [or in this

case languages] and use them in appropriate contexts (as proposed by

code switching models); now minority students have to learn to bring

them together to serve their interests” (pp. 598-599). In other words,

students must learn strategies for negotiation, knowing when to mesh the

dominant discourse with a variety of nondominant discourses in

appropriate academic settings. Code meshing worked well in the digital

narratives assignment, because the English language learners were

allowed to utilize their native languages in order to introduce domestic

students to a vast array of voices. Indeed, it was a true global

representation of language and culture, which was one way to celebrate

language diversity in our class.

Because my students had never heard of code meshing, I felt it

was imperative to introduce the strategy at the beginning of the unit.

Indeed, most students were previously taught to write in a very

formulaic academic style and had never had the freedom to create texts

by blending or meshing multiple languages. Therefore, we discussed code

meshing as a rhetorical strategy and analyzed examples, focusing on how

and when to use code meshing in an academic setting.

Ultimately, code meshing became an effective strategy for both

the English language learners and native speakers. A current movement in

writing instruction, known as the translingual approach, values all

forms of English, asking of writing not whether its language is standard but what the

writers are doing with the language and why. For in fact, notions of the

“Standard English speaker” and “Standard written English” are bankrupt

concepts. All speakers of English speak many variations of English,

every one of the accented, and all of them subject to change as they

intermingle with other varieties of English and other languages.

(Horner, Lu, Roster, & Trimbur, 2011, p. 304-305)

Thus, with so many different dialects of English represented by

both the domestic and international students in a writing classroom,

teaching code meshing as a rhetorical strategy is important, not only

for nonnative speakers of English but also for native speakers. It then

allows students to best communicate with an audience, using their

individual accents. It also values their unique voices and celebrates

diversity.

Overall, I believe it was the multimodal nature of the

assignment that best helped my international students use multiple

linguistic codes to effectively communicate with an audience. Each

student presented his or her digital narrative to the class and

explained the rhetorical strategies he or she used to design his or her

digital narrative. The rhetorical analysis of each text helped the class

understand the overall meaning of the narrative. Takayoshi and Selfe

(2007) have argued that multimodal compositions such as digital

narratives cross “geopolitical, linguistic, and cultural borders” (p.

2). And Shin and Cimasko (2008) have claimed multimodalities provide

English language learners with alternative tools for communicating with

an audience. Therefore, multimodal compositions such as digital

narratives help students, especially English language learners,

communicate effectively with their classmates, offering them creative

opportunities to communicate without depending solely on the written

word. And in this case, the multimodal compositions helped them

effectively blend their first and second languages―a strategy I hope

they will continue to apply in other multimodal and formal writing

assignments.

To blend their languages, the students included sound clips

from their native countries, wrote words or phrases in their native

languages, and even included music from their home countries. Drawing on

their native languages helped them share their languages and cultures

with their audience of international and domestic peers. (See two

sample international students’ digital narratives.)

A Chinese student created the first video in which she shares a

story about playing a prank on her younger brother. Though she does not

use the Chinese language in her narrative, she does include a song by a

Chinese artist. The second video created by a Korean student is a good

example of code meshing. In his narrative, he blended his first and

second languages by including a Korean song and written text.

CONCLUSION

Through this assignment, students learned to blend multiple

languages with a specific purpose. It offered them new rhetorical

choices to help them best communicate with an audience and allowed them

to share their native cultures and languages with their peers. Though

some composition instructors may hesitate to move away from traditional

writing instruction in which standard written English is not a focus, as

Horner et al. (2011) pointed out, writing instruction is moving toward a

heterogeneous model where all voices must be celebrated. Therefore, it

is important for writing teachers to teach all their

students when and how to effectively use code meshing in their writing

assignments.

Little to no research has been conducted on code meshing in

English language learner instruction, as most research still focuses on

code switching. In addition, no research has been conducted on the use

of code meshing in multimodal compositions as a means to effectively

communicate with an audience. I believe both are important bodies of

research, as code meshing and multimodal compositions provide our

students with a variety of rhetorical tools so they can express

themselves and effectively communicate with others.

REFERENCES

Canagarajah, S. (2006). The place of World Englishes in

composition: Pluralization continued. College Composition and

Communication, 57, 586-619.

Horner, B., Lu, M-Z., Roster, J. J., & Trimbur, J.

(2011). Opinion: Language difference in writing toward a translingual

approach. College English, 73, 303-321.

Matsuda, P. K. (2006). The myth of linguistic homogeneity in

U.S. college composition. College English, 68,

737-651.

Shin, D., & Cimasko, T. (2008). Multimodal composition

in a college ESL class. Computers and Composition,

25, 376-395.

Takayoshi, P., & Selfe, C. (2007). Thinking about

multimodality. In C. Selfe (Ed.), Multimodal composition

research for teachers (pp. 1-12).Cresskill, NJ: Hampton

Press.

Tulley, C. (2009). Taking a traditional composition program

“multimodal.” Computers and Composition Online, 2. Retrieved from http://www.bgsu.edu/cconline/Tulley09/.

Erin K. Laverick, PhD, directs the Intensive English

Language Program at The University of Findlay. She is also a member of

the TESOL Standards Committee. Her research interests include second

language writing pedagogies and multimodal

compositions.

APPENDIX

ASSIGNMENT SHEET FOR DIGITAL NARRATIVE

Introduction: For this

assignment you will take your written narrative and transpose it into a

brief 2- to 3-minute visual presentation, using either MovieMaker or

iMovie.

Like the written narrative, we will spend time in a computer

lab so you can workshop. You will also complete a peer review activity

and conference with me. In addition, you are encouraged to visit the

Student Technology Center (STC) for additional help when we are not

working in-class.

Really Super Important: Please save your video to a DVD and turn it in to me

on Wednesday, September 29. You will also need to include the DVD in

your portfolio for the English department to review at the end of the

semester.

Getting Started: We will

first watch sample digital narratives and discuss how the authors

constructed them. You will then do some brainstorming to help you

sequence and organize your video presentation. Also, think about if you

want to include music, voice-overs, etc. How will you transition from

slide to slide? Do you have any cool photos that you can include? Do you

want to re-create a scene for your video?

Requirements: You must include the following in your video:

Introduction: Include a slide with your name, the title of your

video, etc. This will help you set the mood of your video.

Body of the Film:

- Include videos, pictures, and other images that will help you advance your story.

- Include either a voice-over or written narration on the

slides to tell your story. If you do not use a voice-over, you could put

your video to music.

- There must be some oral component to your video.

- When advancing from slide to slide, be sure to add transitions.

Conclusion:

- After wrapping up your story, you must include a final slide

in which you cite the credits. For example, any music, lines from text,

interviews, and/or pictures must be cited. Your credit page should

follow MLA documentation conventions.

|