|

As educators, our primary purpose is to prepare students to

succeed in the future by giving them tasks that they will likely

encounter. In teaching second language (L2) writing in an academic

setting, one challenge instructors face is creating level- and

content-appropriate writing assignments. On the one hand, authenticity

is an important goal, as students need practice with the type of writing

tasks they will see in their future coursework; on the other hand,

topics must be accessible and either dependent on prior background

knowledge or assigned with adequate scaffolding.

The writing curriculum of my intensive English program has

undergone quite a bit of change in the past couple of years as my

colleagues and I have tried to implement more authentic writing tasks

and achieve the balance described above. Student learning outcomes at

the intermediate and advanced levels centered on writing essays of

standard rhetorical forms, such as compare/contrast, problem/solution,

summary/response, and argumentative essays. We felt (and still feel)

that these outcomes build the skills necessary for students to perform

college-level writing. However, we used mainly liberal arts

topics—communication, culture, education, and roles of technology, for

example—because we felt they were accessible and did not present too

much of a cognitive demand on students. Indeed, these topics were

familiar to students and easy to write about.

Based on our internal needs assessments, however, it was clear

that many of our students were going on to majors in science,

technology, engineering, and math (STEM), and needed more authentic

tasks and topics. This realization led to an effort in our writing

program to incorporate different types of tasks and a shift to more

STEM-based topics. In this article, I outline and discuss some of these

writing assignments, which I have used in my own classes.

STEM-Based Tasks

Hands-on Science Activities With Short-Answer Writing

In many cases, I simply wish to give students writing practice

using STEM-related prompts, rather than requiring them to craft complete

essays. I was drawn to activities from elementary school science

classes because they were hands-on and engaging; they were also basic

enough that they did not require sophisticated content background.

One activity was to make homemade flashlights. After reading

some articles and reviewing diagrams of electric circuits and their

components, I gave students a AA battery, a small light bulb, copper

wire, paperclips, and cardboard and tape for mounting. After they all

spent some time assembling the flashlights, each group had quite

unique-looking flashlights, some of which worked more successfully than

others. Following the hands-on activity, I asked the students to write a

short paragraph explaining how their flashlight worked. Sample language

included sentences such as:

First, the electricity flowed from the battery

terminal into the contact on the end of the light bulb. The filament

inside the bulb illuminates and emits light. The electricity flows out

again and through the copper wire to the negative electrode on the

battery. A switch on the wire can either break the circuit or let the

electricity continue flowing.

Another activity involved growing bacteria cultures. I asked

our department to order two sets of petri dishes prefilled with agar. In

groups, students decided which surfaces to swab for their cultures.

After an incubation period, they observed their cultures to see how much

the bacteria had grown and answered a series of short-answer questions

about what happened, which required the use of target vocabulary.

Questions included, “Describe the procedure used for collecting

bacteria,” and “How much did the bacteria replicate?” Key vocabulary

included bacteria, exposure, surface, replicate, incubate, and other content words that we had learned previously in the

course.

Process Writing Assignments

One of the rhetorical patterns in our textbook, which had not

been previously used, was the process pattern. We had been focusing

mainly on the summary/response and argument essays, which promote

critical thinking. However, I realized that the process essay might be

more representative of some of the technical writing our students would

be required to do in STEM classes. In developing the process-writing

component, the main challenge was developing STEM-related prompts that

did not require too much technical background information. Ultimately,

the most successful prompts were those involving diagrams with basic

text (e.g., key words or phrases), such as the water cycle and recycling

of plastic.

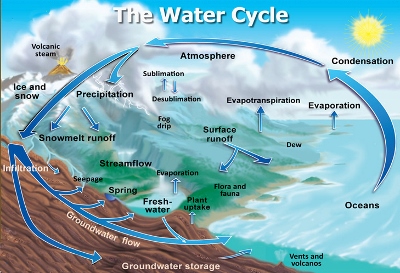

For the water cycle prompt, students were

given a diagram providing them with the most important vocabulary: precipitation, evaporation, runoff, water table, transpiration,and condensation (see Figure 1). They were

then asked to expand their ideas on each step of the water cycle using

examples and details. They also incorporated transitions and signal

words and statistics from outside sources. Given the technical nature of

these topics, students were inclined to take explanations and

definitions from the Internet, and I had to revisit the rules of

citation to avoid plagiarism. Overall, the students did well with this

assignment and seemed to enjoy a fresh topic (ecology) to write

about.

Figure 1. Sample prompt given about the water cycle (Evans & Perlman, 2013).

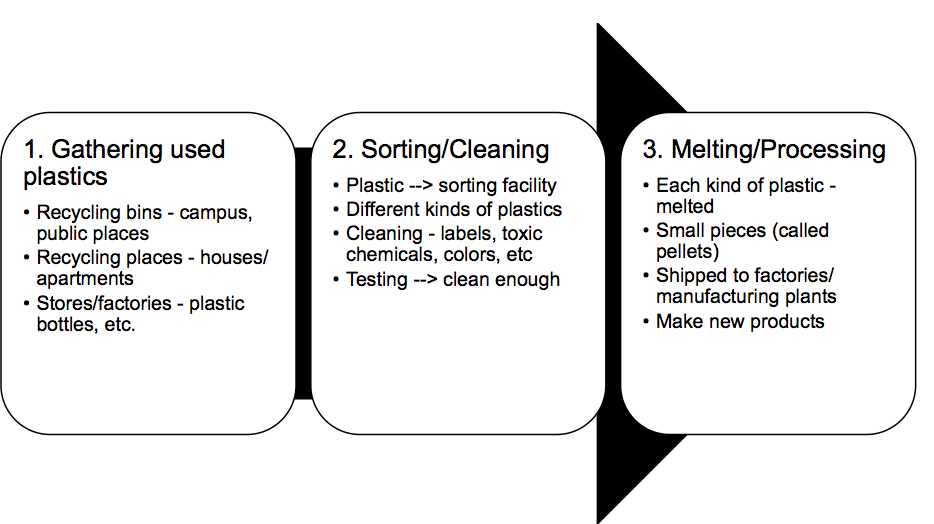

Next, as an in-class writing assignment, students wrote about

how plastics are recycled, basing their essays on a three-step flow

chart that provided them with some key points (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Sample prompt given about recycling plastic.

In this case, my aim was to assess their description skills,

not their knowledge of recycling. Although the goal was not necessarily

to stimulate creative thinking, it was clear from their essays which

students applied themselves to really build and develop their ideas and

which students simply wrote about the basic points on the flowchart. In

either case, this was a topic that students were able to write about

without the need for extensive outside research or specialized

background knowledge.

Lab Reports

One of the initial purposes of delving into STEM writing was

that one of the engineering professors at our university expressed

general frustration about international students not being able to

adequately write lab reports in terms of grammar and format. After

reviewing authentic sample lab reports that the professor provided, I

led two brief in-class activities to teach the basic components of a lab

report: introduction, procedure, results, and conclusion.

The first activity, done together as a class, involved watching

a short YouTube video of a man conducting an experiment to determine how

much sugar is in a can of soda. Together, we wrote a short paragraph

including the purpose statement, materials used, steps, and finally, the

outcome. The second activity required students to write a few

paragraphs based on a set of lab notes I had written, reporting on a

fictitious experiment to test the effectiveness of three types of hand

sanitizers. These notes included the research question, a list of

materials, brief notes on the procedure, and the results, including

photos of the bacteria growth in petri dishes. Students were then able

to utilize the information from the notes and what they observed from

the images to draw conclusions as to the most effective product.

Together, these two smaller writing assignments worked well to provide

my students with a more authentic context to describe a process and

discuss the results. This work also provided the groundwork for them to

conduct and write about their own hands-on lab.

Lab Simulation

Planning a lab for ESL students can be challenging due to

constraints in facilities, equipment, and technical knowledge. Because I

needed something for students to do in the classroom, I fell back on a

previously studied topic: the absorbency of diapers. From experience, I

knew that students enjoyed the process of extracting the tiny granules

from a diaper and watching them expand to absorb a large quantity of

dyed water. This time, however, I wanted to expand the activity to

compare three brands of diapers. In pairs, students took one diaper from

each brand to collect qualitative data on each, including softness and

elasticity. They also recorded the dimensions of the diapers and their

cost. Then, they measured the absorbency by pouring dyed water onto each

diaper and recording the amount at saturation, which provided an

engaging hands-on activity on which to base their papers.

In a multidraft formal report, students included an

introduction on the purpose of this experiment. The second section was a

description of each diaper, based on their notes, and the third section

described in detail—using the passive voice, where possible—the

procedure used to measure absorbency. Below is an (unedited) example

from one student, showing effective use of the passive voice:

Once the measurement and observation were taken, each edge of

diaper were cut to extract its granules which is found on the padding of

the diaper. After extracting the granules, they were poured into a

plastic cup. Then, colored water, which is used to give better

visibility in absorbency, was added until the material was saturated.

Eventually, the capacity of the water that was observed was

recorded.

Finally, the conclusion of their reports gave a recommendation

of which brand was the best buy overall based on the results of their

experiment.

Conclusion

The activities above illustrate that using STEM topics provided

engaging and authentic writing practice and preparation for the types

of writing many L2 students will see in their university coursework. It

can be challenging to select topics that are basic enough not to need

extensive preparation and/or background knowledge, but I have found

using elementary science topics to be effective with and engaging to

students. These topics naturally provide good opportunities to use the

grammar structures learned in class, such as sentence combining,

transitions, and the passive voice, and STEM-based writing has provided a

refreshing change from our program’s once heavily liberal arts–laden

topics.

Reference

Evans, J., & Perlman, H. (2013). Water-cycle diagram

(English). U.S. Department of the Interior & U.S. Geological

Survey. Retrieved from https://water.usgs.gov/edu/watercycle.html

Heather Torrie is the testing coordinator in the

English Language Program at Purdue University Northwest. She has been

teaching academic writing for the past 9 years. |