|

The experience of learning another language can be frustrating

and time consuming, yet it can also be rewarding. As Hanauer (2012)

states, “learning a language is a significant, potentially

life-changing, event” (p. 1). For second language (L2) writers, the

challenges come from not only the English language, but also from the

newness of various writing genres and language structures and the

difficulty of avoiding plagiarism. Many compositionists argue that

creative writing can help L2 writers gain academic literacies, which

includes academic writing. Others argue that creative writing has no

place in the scholarship on academic writing. Bizzaro and Baker (2014)

argue that in order to place social equity in composition classrooms,

“we [must] begin with genres from the students’

cultures” (p. 173). Creative writing is one way to encourage students to

use their rich backgrounds and experiences they bring into the

classrooms.

Sullivan (2015) asserts that creative writing has a place in

composition classrooms because it helps promote “curiosity, openness,

engagement, persistence, responsibility, flexibility and metacognition”

(p. 16). Bizzaro and Baker (2014) also support the use of creative

writing in composition classrooms because “it provides an opportunity

for students to employ genre knowledge from their first language,

knowledge that is socially constructed, and provides a foundation for

students to build upon” (p. 177). Because many students are taught to

focus on English grammar in their language learning experiences, they

tend to pay more attention to structural levels at an early stage of the

writing process. Additionally, many L2 students who are educated in the

context of English as a second or foreign language are taught to focus

more on accuracy than fluency in their English writing classes; they may

have very limited opportunity to practice academic writing in English.

Hanauer (2012) argues that creative writing helps L2 writers express

their ideas without worrying about grammatical structures and promotes

fluency in their writing skills.

Creative writing also allows L2 writers to use their personal

and cultural knowledge in composition classes. A literacy narrative

falls into the category of creative writing because it allows students

to be creative, open, and flexible in their writing and how they

represent their literacy experiences. For L2 writers, literacy

narratives promote critical thinking, a sense of empowerment, and agency

in their own reading and writing experiences. Hanauer (2012) takes this

a step further to ask L2 writers to compose their literacy narratives

in poetic format. He supports the idea that poetic writing is meaningful

for L2 writers, and students are expected to work on an extended

project that combines creative writing and narratives in a poetic

format. Toward the end of the extended project, these writers are

expected to present their creative work in book format. In other words,

students are encouraged to design and “publish” their poetry books,

which gives them a sense of ownership and pride in their work (Hanauer,

2012).

One might wonder what skills these L2 writers learn from doing

this extended project or the creative writing projects. In this article,

we explore the following question: How did a literacy narrative

assignment help L2 writers express their emotions?

L2 Writers’ Literacy Narratives

In this section, we describe the experiences of three

undergraduate L2 writers who were enrolled in a composition class in

which they were asked to write and create poetry books focusing on their

literacy practices at a university in the United States. After the

semester ended, they were asked to reflect on their experiences working

on their poetry books in a composition course and how this assignment

helped them develop their writing skills and build their confidence as

L2 writers.

Many international students feel anxious when they come to

study in another country, and these three students also faced the same

feeling of doubting their own language abilities and proficiency when

they came to the United States for their education. As reflected in

their short narratives below, their experiences in working on a poetry

book assignment helped them successfully express their emotions in the

English language. The following statements are excerpts from Monica,

Felipe, and Adnan about how the poetry book assignment gave them

confidence in writing in English. The statements are unedited, except

for length.

Monica’s Narrative

For the poetry book I choose talking about love, childhood,

adolescence, family, friends, and my cat. I choose these subjects

because it was the deepest aspect about me. It would be rewarding going

back to past experiences. Once I learned we should present a chosen poem

in front of the class after the conclusion of the book, I thought

whether I would be able to communicate feelings in English. In my native

language I mostly do not have the need to choose words to express

feelings. It is a natural process that does not occurs in the second

language. Therefore I would have to be careful in order to communicate

the right thing!

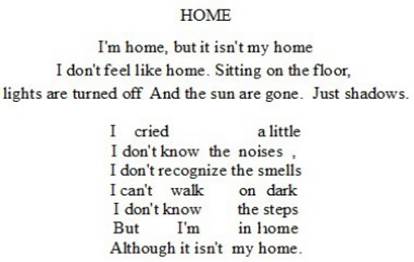

For the book presentation, I choose the poem represented in

Figure 1 (below). While I was writing the book, my experience in English

was very little. Today, after 1 year and a half, I can notice grammar

issues in the poem I was not able to perceive at that moment.

Figure 1. A sample of a poem by Monica.

When I finished reading it out loud to the class, a classmate

told us: “I really liked hearing this poem because it describes exactly

how I feel.” Others agreed with their heads and facial expressions. Then

I realized I reached the point where I could share my feelings in a new

language. That moment was rewarding. I felt accomplished and happy.

Felipe’s Narrative

Creating the poetry book reduced my anxiety towards writing

because this assignment was a free space where I could just write and

not be wrong about syntax, content, and even grammar.

Adnan’s Narrative

During the first week of class, we were told we had to write a

poetry book for our first assignment. I was intimidated and surprised to

say the least. Back in Kuwait, most of my Arabic classes were about

poems but we didn’t write poems. We had to study the grammar of the

poems and memorize them. I didn’t enjoy these classes at all. My first

thought was “Will I be able to do this?” However, having seen some

examples of poems written by fellow ESL students in class, I slowly

began to have confidence that this class going to be a very different

experience and I was correct. I struggled during the first draft but

slowly began to enjoy writing poems.

Expressing emotions through writing can be a very difficult

task for many international students because of the barrier in finding

appropriate emotive words in English (Chamcharatsri, 2013). The excerpts

from the three L2 students touch on the challenges they faced

expressing their emotions in writing but show that they soon learned to

exercise agency in the writing process. Monica, through feedback from

her peers, realized that she had “…reached the point where I could share

my feelings in a new language. That moment was rewarding. I felt

accomplished and happy.” Monica’s emotion was understood by other

classmates. Felipe had also felt anxious when he was asked to write

poems in English. However, he later reflected on his experience and

realized that poetry writing helps him reduce his anxiety in English

writing. Adnan also felt unsure and experienced self-doubt when he was

told that he would write English poems, but his self-doubt began to

subside when he read poems written by other ESL students. Though he

admitted having difficulties in writing his first draft, his perception

changed after that. He became confident in his writing ability.

Conclusion

Because many writing classes ask students to write narratives,

it is an effective genre for students to reflect on their learning

experiences. As Sharma (2015) argues, “writing ‘about’ the experience of

learning to read and write can greatly promote students’ development of

critical sensibilities, capacity for intellectual judgment,

independence as writers and makers of knowledge, self-confidence and

self-respect and, in short, their epistemological agency” (p. 109). Not

only do they have an opportunity to reflect on their learning

experiences, but they also learn how to express emotions through writing

in a creative outlet. This helps students gain confidence and agency in

their language learning journey.

References

Bizzaro, P., & Baker, J. (2014). The poetic and the

personal: Toward a pedagogy of social equity in English language

learning. Teaching English in the Two-Year College,

42(2), 172–186.

Chamcharatsri, P. B. (2013). Emotionality and second language

writers: Expressing fear through narrative in Thai and in English. L2 Journal, 5(1), 59–75.

Hanauer, D. I. (2012). Meaningful literacy: Writing poetry in

the language classroom. Language Teaching, 45(1),

105–115.

Sharma, G. (2015). Cultural schemas and pedagogical uses of

literacy narratives: A reflection on my journey with reading and

writing. College Composition and Communication,

67(1), 104–110.

Sullivan, P. (2015). The unessay: Making room for creativity in

the composition classroom. College Composition and

Communication, 67(1), 6–34.

Bee Chamcharatsri is an assistant professor at the

University of New Mexico. His scholarly interests include emotions and

writing, creative writing, world Englishes, and writing center

research.

Mônica Garcia is an undergraduate student in the Music

Department at the University of New Mexico.

Felipe Rodriguez Romero is an undergraduate student in

the Psychology Department and the Honor’s College at the University of

New Mexico.

Adnan Mohamad is an undergraduate student in the

Chemical Engineering Department at the University of New

Mexico. |