|

In this article, I apply Fishman’s 1990 Graded

Intergenerational Disruption Scale (GIDS) for threatened languages to

Bolivia’s indigenous languages. In doing so, I demonstrate the

complexity of implementing language maintenance and revitalization

policies in extremely multicultural and multilingual countries like

Bolivia as a result of the different stages of the GIDS at which the

languages in their territories are. First, I offer a language profile of

the country. Second, I analyze recent legislation, namely the 1994

Educational Reform and the 2009 Constitution. Last, drawing on the

aforementioned documents and on data from Ethnologue: Languages

of the World (Lewis, 2009) and the Bolivian 2001 census

(República de Bolivia, 2001), I discuss the endangerment situation for a

number of Bolivian indigenous languages in terms of intergenerational

transmission, which constitutes the most used factor in language

vitality assessment (Brezinger et al., 2003).

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Various researchers (see Hornberger & King, 2001;

Malone, 2004)

[2]

have employed the GIDS (Fishman, 1990; further revised in Fishman,

1991, 2001) as an endangerment assessment tool. It is through this

framework that I analyze the indigenous languages of Bolivia in this

article. Table 1 shows Fishman’s model as summarized by Malone (2004, p.

14).

TABLES AND FIGURES

Table 1. Fishman’s Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale for Threatened Languages

|

Weak side |

|

|

|

|

Stage

8 |

Stage

7 |

Stage

6 |

Stage

5 |

|

So

few fluent speakers that the community needs to re-establish language norms;

requires outside experts (e.g., linguists). |

Older

generation uses the language enthusiastically but children are not learning

it. |

Language

and identity socialization of children takes place in home, community. |

Language

socialization involves extensive literacy, usually including L1 schooling. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Strong side |

|

|

|

|

Stage

4 |

Stage

3 |

Stage

2 |

Stage

1 |

|

L1

used in children’s formal education in conjunction with national or official

language. |

L1

is used in workplaces of larger society, beyond normal L1 boundaries. |

Lower

governmental services and local mass media are open to L1. |

“cultural

autonomy is recognized and implemented” (Fishman 1990, p. 18); L1 used at

upper government level. |

LANGUAGE PROFILE OF BOLIVIA

Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Lewis,

2009) lists 45 languages for Bolivia: 37 living languages, one second

language with no native speakers (Callawalla), and seven with no known

speakers (Canichana, Cayubaba, Itene, Jorá, Pauserna, Shinabo, and

Saraveca

[3]).

Although all living languages were given official status in the

2009 Constitution (República de Bolivia, 2009), the de facto majority language is Spanish. Bolivia’s indigenous languages

could be further divided in two groups: major minority languages

(Quechua, Aymara, and Guaraní) and lesser minority languages (the rest).

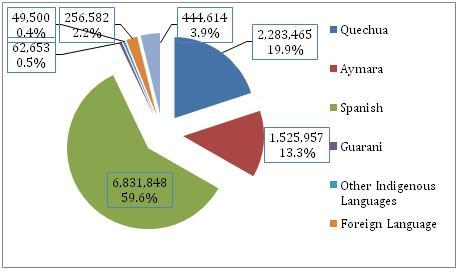

Figure 1 shows the data regarding the mother tongue of

Bolivians 4 years of age and older in the 2001 Census. This chart gives a

clear idea of the numeric superiority of Spanish (59.6%).

Figure 1. Native Language of the Bolivian Population 4 Years of Age and Older

Note: Percentages do not add one-hundred due to rounding.

Source: 2001 Census, Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Bolivia

Many of the lesser minority languages have a small number of

speakers but are stable, that is, they are being transmitted

intergenerationally, and are spoken by all, or almost all, the members

of the ethnic group as is the case for Araona, Yaminahua, and Yuqui.

Other languages (seeTable2) are reported as nearly extinct.

Table 2. Nearly Extinct Bolivian Indigenous Languages

|

Language Name |

Number of Speakers |

Ethnic Population |

|

Baure |

13 |

631 |

|

Itonama |

10 |

5,090 |

|

Leco |

20 |

80 |

|

Pacahuara |

17 |

18 |

|

Uru |

2 |

142 |

STATUS PLANNING AND LANGUAGE POLICY

Status planning constitutes a crucial step in both language

maintenance and revitalization. According to Wiley (1996, p. 108), it

has two main dimensions: (1) official recognition given by governments

and (2) attempts to extend or limit language use in certain domains. The

2009 Constitution of the Republic of Bolivia and the 1994 Bolivian

Educational Reform exemplify these two dimensions.

Language Officialization: The 2009 Constitution of the Republic of Bolivia

The official recognition of an indigenous or minority language

plays an important role in the perception society has of the language

and its speakers. The new Bolivian Constitution adopted on February 7,

2009, states in Article 5 that “the official languages of the State are

Spanish and all the languages of the indigenous nations and peoples” (My

translation). But have Bolivia’s indigenous languages always had

official status?

The 1967 Constitution of the Republic of Bolivia (República de

Bolivia, 1967) completely ignored the country’s multiethnic and

multilingual reality. It was not until it was amended in 1994 that this

reality was acknowledged for the first time. The 1994 amendment to the

1967 Constitution (later approved as the 1995 Constitution; República de

Bolivia, 1995) recognized the country as multiethnic and multicultural

(Article 1). However, indigenous languages were mentioned only in

Article 171, which addressed the cultural rights of indigenous peoples

and guaranteed the use and development of their resources, values,

languages and institutions. Although these two articles obviously

constituted a step forward for indigenous languages, there was still no

explicit mention of an official language. Thus Spanish continued to

profit from the implicit official language status it had had up to that

moment. Fortunately, this state of affairs changed in 2000 when

President Banzer passed a law (Decreto Supremo 25894;

República de Bolivia, 2000) making 35 indigenous languages official

languages of the state (Taylor, 2004).

Making all of the country’s languages official in 2000 and

including them in the 2009 Constitution constituted two major steps

toward their maintenance and revitalization. However, the 2009

Constitution not only includes all the languages but also provides

support for indigenous languages through promotion of multilingual

education and language revitalization. The new constitution supports

multilingual education by saying that “education is intracultural,

intercultural, and multilingual in the entire

educational system” (My translation, emphasis added) in Part II of

Article 78. The important role of multilingual education as a means of

intercultural understanding and respect is clearly stated in Article 80:

“education shall contribute to . . . the identity and cultural

advancement of all . . . indigenous nations and peoples and to the

intercultural understanding and enrichment within the state” (My

translation).

Language Policies: The 1994 Educational Reform

Status planning “involves some type of official and/or

medium-of-instruction policy” (McCarty 2008, p. 142). In the case of

Bolivia, these policies have come in the form of educational reforms in

1905, 1955, and 1994.

The 1905 reform centralized the country’s education and sought

to strengthen education available to indigenous communities. However,

language diversity was seen as a problem “to be overcome through castellinización

[4]”(Taylor, 2004, p. 8). In the 1955 reform,

language diversity continued to be viewed as an obstacle to national

unity; this time, however, a concession was made regarding instruction

in indigenous languages: They could be used as a means for attaining

Spanish literacy in regions where the indigenous languages were the

majority language (Taylor, 2004, p. 10). For more than 80 years, the

Bolivian educational system promoted a single national language, that

is, Spanish. It was not until July 7, 1994, that a new educational

reform introduced bilingual education.

The main contribution of the Reforma Educativa de 1994(Ley No. 1565; República de Bolivia,

1994)is that it declares Bolivian education to be intercultural and

bilingual (Article 5). It further clarifies in its Article 9 that

language education comprises two modalities: monolingual (L1 Spanish

with an indigenous language as L2) and bilingual (L1 indigenous language

with Spanish as L2). Another merit of this reform is that it encourages

active popular participation in the planning, organization, and

evaluation of education through the establishment of the Consejos Educativos de Pueblos

Originarios

[5] (Article 11, Section 5). According to the

reform, the four councils―Aymara, Quechua, Guaraní, and Multiethnic

Amazon―and others have a national character and can participate in the

development and application of educational policies, especially those

related to multiculturalism and bilingualism. Other regulations equally

relevant for indigenous languages are equal access for lower income

children (Article 53), an adult literacy campaign (Article 26), and the

organization of the núcleos

educativos

[6] (Article 31), which takes into account the

community’s interests, culture, and language, thus making language (and

culture too) an important criterion in the organization of the

educational system.

DISCUSSION

In my analysis, I apply Fishman’s GIDS to Bolivia’s three major

minority languages, namely Aymara, Guaraní, and Quechua, as well as to

six lesser minority languages, specifically Araona, Baure, Itonama, Uru,

Yaminahua, and Yuqui.

Taking into account only the 2009 Constitution and the 1994

Educational Reform could potentially lead to the idea that all Bolivian

indigenous languages are now on the strong side of Fishman’s GIDS, that

is, Stages 4 to 1. However, this is not the case; different indigenous

languages are at different stages as the following analysis shows.

As previously seen in Figure 1, Aymara, Guaraní, and Quechua

have relatively high numbers of speakers compared with the country’s

other minority languages. All three are also transmitted

intergenerationally (consider the large numbers of children and youth

that speak the language as shown in Table 3).

Table 3. Number of Speakers of Three Major Minority Languages by Age Groups

|

AGE |

Quechua |

Aymara |

Guaraní |

|

0-9 |

333,696 |

148,117 |

10,715 |

|

10-19 |

450,739 |

266,316 |

11,928 |

|

20-29 |

395,348 |

285,672 |

10,950 |

|

30-39 |

339,332 |

257,802 |

9,047 |

|

40-49 |

291,686 |

217,249 |

7,642 |

|

50-59 |

205,257 |

154,579 |

5,482 |

|

60-69 |

139,274 |

103,384 |

3,793 |

|

70-79 |

92,122 |

67,815 |

2,222 |

|

80-89 |

28,801 |

20,055 |

722 |

|

90-99 |

7,210 |

4,968 |

152 |

Source: 2001 Census, Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Bolivia

Von Gleich (2004) speaks of a La Paz newspaper, Presencia, which published daily for a year

(1999-2000) one page of local and international news in Quechua and

Aymara, as well as the Revista Nawpaqman, Revista rural

bilingüe para la nación quechua

[7] and a Quechua radio network.

As for Guaraní, López (2001) stated that “the Guaraní language is not

only used in radio transmissions and programs but also in posters,

signs, leaflets” (p. 218). Adding the existence of local mass media in

all three languages to the numbers in Figure 1 and Table 4 as well as

the official status granted to them by the 2009 Constitution and their

inclusion in the school system as stipulated by the 1994 Educational

Reform, one could claim that these languages are between Stages 3 and 2

of Fishman’s GIDS, where the L1 is used beyond its normal boundaries and

lower governmental services and mass media are open to it.

In Table 4 I compare two groups of lesser minority

languages―Araona, Yaminahua, and Yuqui and Baure, Itonama, and Uru―based

on their number of speakers, ethnic population, and language use as

described by Ethnologue: Languages of the World

(Lewis, 2009).

Table 4. Six Lesser Minority Languages: Araona, Baure, Itonama, Yaminahua, Yuqui, and Uru

|

Language |

Number of Speakers |

Ethnic Population |

Language Use |

|

Araona |

81 |

90 |

Vigorous. All ages. |

|

Yaminahua |

140 |

161 |

All ages. |

|

Yuqui |

120 |

138 |

Also use Spanish. |

|

Baure |

13 |

631 |

Shifting to Spanish. |

|

Itomana |

10 |

5090 |

Shifting to Spanish. Older adults. |

|

Uru |

2 |

142 |

Now speak Spanish or Aymara. |

On the one hand, Araona, Yaminahua, and Yuqui are spoken by

almost all members of their respective ethnic groups and widely used

(see last column in Table 4 for Language Use), which means that they are

being transmitted intergenerationally and that the children are

learning the language in the community. On the basis of these data and

their official status and the L1 schooling prescribed by the 1994

Educational Reform,

[8] these languages should be included in Stages 6

and/or 5 of the GIDS, at which the language socialization takes place

at home and in the community but where the schooling in L1 is available.

On the other hand, Baure, Itonama, and Uru are spoken only by a few

older speakers who are shifting to Spanish: 2.1%, 0.2%, and 1.4% of

their respective ethnic populations speak the language. There are so few

fluent speakers in these communities that the languages need to be

reintroduced and, in order to attain this goal, outside help will be

required as predicted by Stage 8 of Fishman’s scale at which, one could

conclude, they are situated.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

The precarious situation of languages such as Baure, Itomana,

and Uru suggests that Bolivia needs to do more than give official status

to its indigenous languages and include them in the school system; more

work is required in the implementation of these policies. The

difficulty of such an endeavor lies in the different stages of the GIDS

at which the country’s indigenous languages are situated: that is,

Aymara, Guaraní and Quechua at Stages 3 and/or 2; Araona, Yaminahua, and

Yuqui at Stages 6 and/or 5; and Baure, Itonama, and Uru at Stage 8.

This suggests that national policies like the 1994 Educational Reform

and the 2009 Constitution need to be tailored to each particular

language and community.

REFERENCES

Brezinger, M., et al. (2003). Language Vitality and

Endangerment. UNESCO. Retrieved from

http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/doc/src/00120-EN.pdf

Fishman, J. A. (1990). What is reversing language

shift (RLS) and how can it succeed? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development,

11, 5-36.

Fishman, J. A. (1991). Reversing language shift:

Theoretical and empirical foundations of assistance to threatened

languages. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Fishman, J. A. (2001). Why is it so hard to save a threatened

language? (A perspective on the cases that follow). In J. A. Fishman

(Ed.), Can threatened languages be saved?: Reversing language

shift, revisited: A 21st century perspective (pp. 1-22).

Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters Press.

Hornberger, N. H., & King, K. A. (2001). Reversing

Quechua language shift in the Andes. In J. Fishman (Ed.), Can

threatened languages be saved? Reversing language shift, revisited: A

21st century perspective (pp. 166-194).

Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters Press.

Krauss, M. (1992). The world’s languages in crisis. Language, 68, 4-10.

Lewis, M. Paul (Ed.). (2009). Ethnologue: Languages of

the World [Online version] (16th ed.). Dallas, TX: SIL

International. Retrieved from http://www.ethnologue.com/

López, L. E. (2001). Literacy and Intercultural Bilingual

Education in the Andes. In D. R. Olson and N. Torrance (Eds.), The making of literate societies. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Malone, D. (2004). The in-between people: Language

& culture maintenance and mother-tongue education in the

highlands of Papua New Guinea. Dallas, TX: SIL International.

McCarty, T. L. (2008). Language education planning and policies

by and for indigenous peoples. In S. May & N. H. Hornberger

(Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education (2nd

ed., Vol. 1, pp. 137-150). Boston, MA: Springer.

República de Bolivia. (1967). Constitución Política

del Estado de 1967. Retrieved March 4, 2010, from

http://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Bolivia/bolivia1967.html

República de Bolivia. Congreso Nacional. (1994). Ley

de Reforma Educativa (Ley 1565). Retrieved March 4, 2010, from

http://www.congreso.gov.bo/leyes/1565.htm

República de Bolivia. (1995). Constitución Política

del Estado (Ley 1615). Retrieved March 4, 2010, from

http://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Bolivia/consboliv2005.html

República de Bolivia. (2000). Decreto Supremo No

25894. Retrieved March 4, 2010, from

http://www.congreso.gov.bo/archivo/texto/25894.htm

República de Bolivia, Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE).

(2001). Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda.

Retrieved March 4, 2010, from http://www.ine.gov.bo/

República de Bolivia. (2009). Constitución Política

del Estado. Retrieved March 4, 2010, from

http://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Bolivia/bolivia09.html

Taylor, S. 2004. Intercultural and

Bilingual Education in Bolivia: The Challenge of Ethnic Diversity and

National Identity (Instituto de Investigaciones

Socio-Económicas Working Paper No. 01/04). La Paz: Universidad Católica

Boliviana.

von Gleich, U. (2004). New Quechua literacies in

Bolivia. International Journal of the Sociology of Language,

167, 131-146.

Wiley, T. G. (1996). Language planning and policy. In S. McKay

& N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Sociolinguistics and

language teaching (pp. 103-127). New York, NY: Cambridge

University Press.

Jorge Emilio Rosés Labrada, Department of French Studies, The

University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada, jrosesla@uwo.ca

Jorge Emilio Rosés Labrada, Department of French Studies, The

University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada, jrosesla@uwo.ca

[1] The numbers of languages and their speakers

were all taken from the online version of Ethnologue: Languages of the

World (Lewis, 2009), unless otherwise specified.

[2]

Caveat: Although the importance of intergenerational transmission has

been widely recognized, some scholars have objected to Fishman’s 1990

GIDS as an endangerment assessment tool. The 2003 UNESCO document

“Language Vitality and Endangerment” is considered a more complete

assessment tool (Brezinger et al., 2003) but

Fishman’s GIDS will suffice for the purposes of this article.

[3]

Three of these are considered to be extinct and four are reported as not

having any known speakers.

[4]

As Taylor (2004) accurately pointed out, this term refers to both

cultural and linguistic assimilation into Spanish.

[5] Indigenous Peoples’ Educational Councils.

[6]

Defined as the network of schools that provide education to an area or

community.

[7] Nawpaqman Review: A rural bilingual journal for the

Quechua nation

[8] I

could not confirm whether L1 schooling in these languages is actually

taking place in the communities but base this analysis solely on the

provisions for mother tongue instruction of the Educational Reform. |