|

The inauspicious COVID-19 has shaken up the landscape of bilingual education. It moves classes typically held in a face-to-face setting to a totally or partially remote online platform. Thus, instead of using traditional methods of teaching English vocabulary, literacy teachers in bilingual programs find it crucial to create an interactive learning. The potentials of using emerging technologies to introduce strong forms of bilingual education for English language learners have been long proposed (Bourguet et al., 2006). Nevertheless, not many practical implications have been made in teaching writing in content area instruction.

This article aims to fill that gap in literature by examining the effectiveness of a design-based sequence of teaching vocabulary in contexts of use. A teaching sequence was applied, combining the use of visual thesaurus (https://visuwords.com/), corpus-based collocation dictionary (https://ludwig.guru/), and Google Form to help with students' word acquisition and word choice in writing.

Designing an in-depth online instruction for vocabulary selection and collaborative writing

Bilingual learners struggle with articulating thoughts in writing, causing more target-oriented unusual or non-collocational wording, even after a long period of instruction (e.g., Wells, 2013). That unique struggle is caused by the conceptual inequivalences between two languages that confuse the writers and complicate the word selection in a specific context (Pavlenko, 2009). For example, the concept underlying the word "individualism" is not equal in China and the USA. While individualism lies in the core of American ideology, it elicits the concept of a selfish person who pursues individual freedom rather than following the group interests, thus hindering society's development in China. In other words, on the conceptual level of the word “individualism,” the inter-connected conceptual networks of the word “individualism” trigger different aspects of meanings in each language.

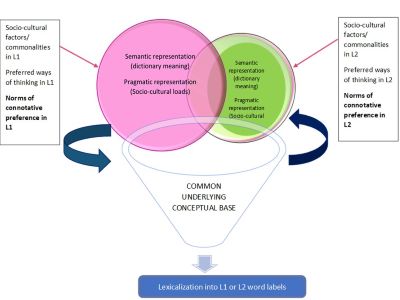

Those conceptual inequivalences are derived from the preferred ways of encoding thoughts in a socio-cultural context of a language speech community. A language user’s private meaning construction is varied depending on socio-cultural background, prior experience with the words, word familiarity (see Figure 1). That acquisition of norms of word usage is called "social conceptualization." In a bilingual's mind, the knowledge gained from social conceptualization in each language is stored in one unified conceptual base called "Common Underlying Conceptual Base" (CUCB). The lack of understanding socio-cultural conceptual meanings in one language can lead to the inaccurate use of words when the language user communicates with the audience from that language community. This study found that if a Chinese-English bilingual student is not aware of the differences in the word connotation between two languages, they tend to use the word "individualistic" or "individualism" inappropriately. One student wrote, "Some of them cannot get along with colleagues because of the individualism." Another student wrote, "Some of them are individualistic; they do everything just good for them and think they are unique."

The understanding of such word associations and networks across languages is critical in of multilingual pedagogy. Students need to understand the socio-cultural salience to select words collocationally, which is a matter of pragmatic competence (Kecskes, 2011). Hence, teachers need to focus on explicit instruction about vocabulary in contexts of use and familiarize students with socio-cultural conceptual differences. The online learning environment provides a valuable opportunity to visually present the synonymic (or antonymic) relationship of words and the collocational use of words in contexts (Chill, 2013).

Figure 1. The blending of factors that affect word knowledge in a bilingual’s mind (visualized from the Conceptual Blending Hypothesis of Kecskes, 2011)

Research Question and Data Sources

The guiding questions for the study were, "How did the English language teachers utilize technological tools for enhancing vocabulary selection in a written context? How did students feel about using those tools to enhance their abilities to use words in context?"

Forty-five Chinese university students majoring in Sociology participated. They were taking the last two years of their undergraduate program in the USA. It was a bachelor's degree in Sociology awarded by both the university in China and its collaborative partner program in the USA. The goal for these students is biliteracy in both Chinese and English when it comes to the knowledge of their major. When COVID-19 broke out, their Academic Writing class was moved online. A technologies-mediated sequence for teaching vocabulary was implemented for observation throughout 12 weeks.

After the intervention, students completed a take-home assignment, focusing on an academic topic: "What is the importance of social mobility?" They wrote it in their mother tongue first and then in English, their second language. Class observations and content analysis of the essays were conducted. Two English native-speaking teachers independently (inter-encoder agreement of 80%) rated the essays, highlighting the inaccurate word combinations. The content analysis was triangulated with the students' questionnaire.

Major findings

1. The use of visual thesaurus and corpus-based dictionary in vocabulary instruction for bilingual learners

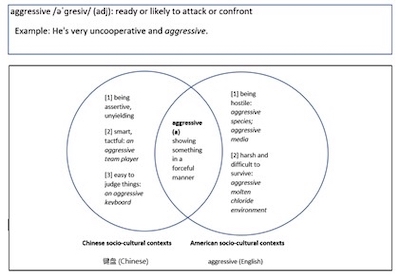

The class observations reveal how the teacher uses the e-tools to engage students in identifying the relationship between words and corresponding concepts. First, students analyze a word in different contexts of use in English. In pairs, students deduce the meaning of words in those contexts and relate those meanings to the first language's background. For instance, in Chinese culture, the conceptual meaning underlying the noun "aggression," or the adjective "to be aggressive," indicates a positive mindset of being assertive, unyielding, and smart rather than demonstrating physical strength. Thus, "an aggressive person" means a well-prepared person ready to compete with others. "Aggressive" in the Chinese context can also be used to indicate "键盘" (an aggressive keyboard warrior), which means a netizen who is ready to judge and lash out at other people on the Internet but are not brave enough to do so in real life. The words are collocationally used to describe [pride], [determination], [an eager to win] or [a coward showing off online].

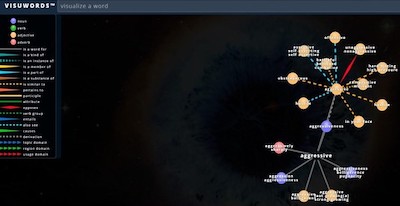

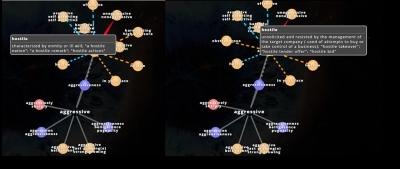

After students explore the lexical concepts in the first language, students use the visual thesaurus dictionary (https://visuwords.com/) to explicitly explain the conceptual networks in the American contexts. Students investigate the conceptualization of the word "aggressive" in American contexts in Visuwords (Figure 2). This word activates a negative conceptual domain,"(being eager to) using physical force to combat" and triggering the context of war or competition (in sports). The word does not conceptually equate with a positive meaning as in Chinese contexts. Students summarize each aspect of conceptual meaning, such as seeing how "aggressive" can be used to depict varying degrees of "being hostile" (Figure 3). The teacher stimulates a conversation to distinguish the differences in conceptual meanings of "aggressive" between two languages in a Venn diagram. Such compare-and-contrast activity supports the metalinguistic awareness and facilitates the reconstructing of word concepts (Figure 4).

Figure 2. The semantic analysis of the word "aggressive" on Visuwords

Figure 3. The word "aggressive" and its concept of [being hostile] in different contexts: the physical strength (on the left) and a manner of business competition (on the right)

Figure 4. The vocabulary instruction using dictionary meaning and e-tools

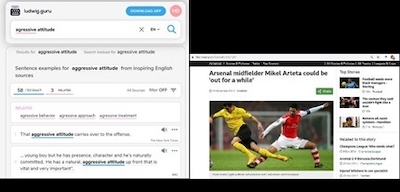

Next, students use the visual thesaurus dictionary in the corpus written by English native speakers (https://ludwig.guru) to compile more collocational pairs (see Figure 5). Assuming a student wants to combine "aggressive" with "attitude," instead of relying on word-by-word translation, the student critically evaluates his wording using the corpus and the Venn-diagram (Figure 4).

Figure 5. The use of the word combination "aggressive attitude" in the corpus and the hyperlink to the original source containing the word phrases

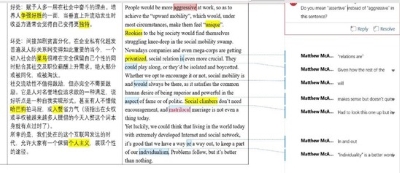

Finally, after studying the target words and their corresponding concepts, students apply those steps into word selection for English essays. The teacher uses the Google Docs for peer-review, asking students to give feedback on word choices. Students need to leave comments explaining why their classmate's word choice is unnatural or non-collocational using the tools (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Google Form for feedback on word usage shared amongst team members

2. Visual thesaurus and corpus-based dictionary in writing and implications for K-12 biliteracy programs

37 out of 45 students (82.2%) reported their strong preference towards using the e-tools and the vocabulary teaching sequence during the pandemic. The number of unnatural and non-collocational words reduced by 53% in the final essay compared with that before the intervention. First, they indicated that learning vocabulary in a collaborative effort with the teacher and peers helped retain the wording better. Second, students enjoyed broadening their vocabulary knowledge in authentic texts to use the whole word phrases. Third, word meaning is not taught but explored and contextualized in both languages, so students could consciously observe the differences in how a word is used in each language's situations. Finally, the peer-review activity helped clear up the confusion about word choices. The e-tools could be employed for further self-regulated learning, delving more into conceptual meanings relevant to students’ needs.

The integration of visual thesaurus and corpus-based dictionary into vocabulary instruction to facilitate the maintenance and development of their students' biliterate abilities can be modified across grade levels and English language proficiency levels. Bilingual students can use these tools to explore word meanings in short sentences. With more complexity of academic words in authentic texts, students can self-monitor the vocabulary capacity in both languages. Taking advantage of e-tools and e-resources for an analytical and student-centered approach towards language use, teachers can nourish biliteracy and transfer skills between languages.

References

Bourguet, M. L. (2006). Introducing Strong Forms of Bilingual Education in the Mainstream Classroom: A Case for Technology. In Sixth IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT'06) (pp. 642-646). IEEE.

Chiu, Y. H. (2013). Computer‐assisted second language vocabulary instruction: A meta‐analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(2), E52-E56.

Kecskes, I. (2011). Salience in language production. Salience and defaults in utterance processing, 81.

Pavlenko, A. (2009). Conceptual representation in the bilingual lexicon and second language vocabulary learning. The bilingual mental lexicon: Interdisciplinary approaches, 125-160.

Wells, N. (2013). Lexical error analysis of advanced language learners' writings (Doctoral dissertation).

Hanh Dinh (MA in TESOL) is currently a doctoral candidate in curriculum and instruction at SUNY at Albany. Her research interests include intercultural pragmatics, bilingualism, and bilingual education. |