Minimizing Cultural Dissonance for SLIFE

by Helaine W. Marshall

Cultural dissonance is the feeling of alienation and not

belonging that students with limited or interrupted formal education (SLIFE)

experience when they come to our schools. This dissonance is a major factor

that TESOL educators need to address in teaching SLIFE because being in school

is itself a challenge for these students. We need to be aware of how the nature

of formal education as we know it poses problems for SLIFE in addition to

focusing on teaching English, literacy skills, and subject-area content.

Three Challenging

Hallmarks of Education

In my recent

work with DeCapua and Tang (DeCapua, Marshall, & Tang, 2020), we

identified three major hallmarks of formal education that challenge SLIFE. These

hallmarks are what I refer to as “deal breakers” because, when SLIFE face them,

they find themselves stuck and unable to function as expected by their teachers

and fellow students. However, teachers can address the cultural dissonance of a

school with culturally responsive (Gay, 2018) and sustaining (Paris &

Alim, 2017) classroom strategies.

These

hallmarks are as follows:

-

The student believes in the

promise of a future reward for education.

-

The student is motivated to

participate and excel as an individual learner.

-

The student can take and

pass various standardized assessments.

(DeCapua,

Marshall, & Tang, 2020, p. 84).

Each of these hallmarks,

or deal breakers, intensifies the cultural dissonance that SLIFE feel because

their own ways of learning differ so much from learning in a formal classroom

setting. We’ll take a look at each of them and consider how a culturally based

framework can minimize these deal breakers by tackling them through a mutually

adaptive pedagogy.

Deal Breaker #1:

Believing in a Future Reward

SLIFE

usually come from backgrounds where learning something new is immediately relevant

to their lives. They are used to learning that benefits them in the short term

and meets their immediate needs. Learning for these students consists primarily

of practical knowledge and pragmatic skills needed by families and their

communities (Paradise & Rogoff, 2009; Rogoff, 2014). When teachers

stress the benefit of education in the long term with a future-oriented

mindset, SLIFE don’t relate to these promised rewards. They find most of what

they are asked to do during the school day irrelevant and less compelling than

what they might be able to accomplish outside of school.

Deal Breaker #2:

Becoming an Independent Learner

More than

70% of the world’s cultures are collectivistic, placing a greater value on the

group than on any one individual (Triandis, 1995). In collectivistic cultures,

people see themselves as highly interconnected and interdependent. SLIFE, who

generally come from countries identified by Triandis (1995) as collectivistic,

find the opposite when they come to an individualistic culture like those in

the United States, Canada, or Australia, which highly value individual and

independent effort in school. SLIFE from collectivistic cultures tend not to be

hand raisers and do not seek recognition, which makes them seem, from our

perspective, less prepared or less motivated to participate. Teachers from

individualistic cultures routinely expect students to demonstrate engagement

and knowledge by raising their hands to respond, by keeping their eyes on their

own work, and by seeking positive feedback for their personal efforts. SLIFE,

in contrast, want to share responsibility with others; they try to maintain and

form webs of relationships and not stand out (Marshall & DeCapua,

2013).

Deal

Breaker #3: Mastering Standardized Testing

Today’s

school calendar is dominated by preparing for high-stakes, standardized

assessments. A close look at what these tests require shows they demand three

skills that are especially challenging for SLIFE. First, there is the just

mentioned individual accountability. Next, there is the reliance on the written

word, so difficult for SLIFE whose literacy skills are still developing and who

communicate best orally. Last, there is the requirement to perform

decontextualized tasks, such as answering multiple-choice, true/false, or

matching questions, which do not imitate the real-world tasks SLIFE are used to

doing. These school-based tasks confuse SLIFE because they see do not

understand their purpose. In the real world, we wouldn’t look at a tree and say

to our children, “That is a tree, true or false?”

To compound

the problem, these decontextualized test questions target types of explicit,

academic thinking, such as comparison/contrast, cause and effect,

classification, and so on, that are unfamiliar to such students. In their

real-world learning experiences, the primary activity is to practice, not to

analyze, or, when SLIFE do analyze, it is from a functional perspective rather

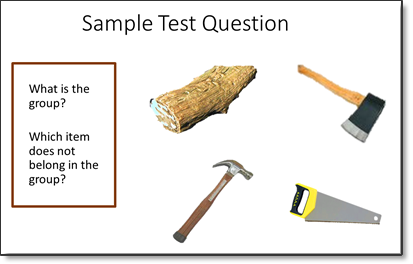

than a school perspective. For example, imagine a test iem showing four images

(an axe, a hammer, a log, and a saw) with these questions: “What is the group?

Which item does not belong in the group?” (Luria, 1976; see Figure 1)

Participants’ task is to decide what class three of the items belong to and

then to select the one item that is not part of that class.

Figure 1. Sample test question. (Luria,

1976)

The class is

“tools”; the item that doesn’t belong is a log because it is not a tool. For

SLIFE, this type of classification based on abstract shared characteristics can

be difficult because they tend to think functionally. They would likely never

remove the log because then they could not use the tools for any purpose. While

their thinking isn’t “wrong,” it is not the type of thinking—here,

classification based on shared characteristics of what makes something a

tool—expected on such assessments (DeCapua & Marshall, 2011; Luria,

1976).

The Mutually Adaptive

Learning Paradigm®

With these

three deal breakers, the cultural dissonance becomes overwhelming to SLIFE;

however, the culturally responsive and sustaining Mutually

Adaptive Learning Paradigm®, or MALP® model (Marshall, 1998), lessens

the effects of these deal breakers. MALP incorporates key priorities about

learning held by SLIFE and places them into a framework that integrates key

elements of formal education.

The basic

premise underlying MALP is mutual adaptation, without which SLIFE encounter

obstacles to their success in U.S. schools. MALP is mutually

adaptive because it asks educators to adapt their pedagogy even as

students are transitioning to Western-style formal education and new ways of

learning and thinking. By including elements from the SLIFE learning paradigm,

as well as elements from the U.S. formal educational learning paradigm, the

priorities of both are honored and incorporated.

MALP

Strategies

Here are the

major MALP strategies that teachers of SLIFE can implement in their classrooms.

1. Create Relevance and

Interconnectedness

Create two

conditions for learning that help SLIFE feel comfortable in school: immediate

relevance and interconnectedness. When SLIFE feel connected to each other and

to their teacher in a personal way and when what they are learning incorporates

at least some element that relates directly to their lives, they are more

likely to engage and participate.

2. Combine Familiar and

Unfamiliar Learning Processes

Combine oral

and written work all through their instructional activities so that there is

constant scaffolding for both low- and high-stakes activities. Alternate

between shared responsibility and individual accountability so that SLIFE can

master both.

3. Develop Academic

Thinking and Provide Scaffolding

Design

explicit lessons and projects to develop academic ways of thinking and

familiarity with decontextualized, literacy-based school tasks. Encourage whole

language repertoires, translanguaging, and English vocabulary that SLIFE have

already learned, along with topics they already know something about, to

provide scaffolding for them as they learn to master these new tasks and

school-based ways of thinking.

Implementing MALP

Strategies

The best way

to implement these MALP strategies is to have students do projects. One MALP

project that can be applied in any learning context is class surveys. For

example, when one teacher, Ms. Arcadio, was teaching SLIFE about nutrition

(DeCapua, Marshall, & Tang, 2020), she began with a class survey on eating

habits and food preferences. Knowing that the academic ways of thinking

underlying the concept of nutrition would be new to SLIFE, she built upon what

was already familiar to them. Together, she and her class generated questions

for the survey, collected data, and analyzed and reported the results.

Though it is

not uncommon for teachers to query students about their eating habits, the

difference here was the creation of a formal survey and the opportunities it

afforded to incorporate MALP. Here is an analysis of her project through the

lens of the MALP model.

-

The questions dealt with

the food in the cafeteria, at home, and in other venues. Rather than learning

in the abstract about nutrition, they were relating it to their lives. Thus,

Ms. Arcadio implemented immediate relevance to students’

lives.

-

The survey itself is by

nature interpersonal and helps to establish and maintain relationships. As the

students and Ms. Arcadio participated in the survey, they learned more about

each other. This personalization of the topic of nutrition built

interconnectedness.

-

The students conducted the

poll orally, noting down responses. Those SLIFE with low literacyrecorded answers orally instead, using

smartphones. Ms. Arcadio and the more proficient students transcribed

responses, which formed the basis for additional literacy skills

development. When they later analyzed the results, students

formed discussion groups and shared a written summary of their

findings. Thus, there were numerous opportunities to move from

oral transmission to print.

-

There wascontinuous collaboration among the students as

they worked together to decide on questions and then as they reviewed and

analyzed their results. However, Ms. Arcadio ensured that there wereindividual tasks built into the project as well.

Each student contributed questions and polled on their own. Each wrote up their

results and produced graphic representations of the data. During the analysis,

Ms. Arcadio paired students to work together, combining their individual charts

into a joint PowerPoint presentation. Through these tasks, thetransition from shared responsibility to individual

accountability was gradual.

-

Once the data were

collected, Ms. Aracdio designed decontextualized tasks to develop

academic ways of thinking, but these were now accessible given

the familiar language and content of their own class survey.

Some examples were calculating the nutritional value of various diets,

identifying patterns in the data, and presenting results in pie

charts.

When

teachers keep in mind the MALP strategies, they will find, as did Ms. Arcadio,

that SLIFE can participate actively and make progress in school-based acivities

because the model creates a learning environment that acknowledges their

background and needs. Because MALP takes elements of the school learning

paradigm and elements of the SLIFE learning paradigm to create a new one, it is

referred to as “mutually adaptive.” To learn more about MALP® and see how it is

implemented, along with examples of projects for a variety of school settings,

please see “MALP

Resources” on the MALP Instructional Approach website.

References

DeCapua, A.,

& Marshall, H. W. (2011). Breaking new ground: Teaching

students with limited or interrupted formal education. University of

Michigan Press.

DeCapua, A.,

Marshall, H. W., & Tang, F. L. (2020). Meeting the needs of

SLIFE: A guide for educators. University of Michigan

Press.

Gay, G.

(2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research and

practice (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Luria, A. R.

(1976). The making of mind. Harvard University

Press.

Marshall, H.

W. (1998). A mutually adaptive learning paradigm for Hmong students. Cultural Circles, 3,135–149.

Marshall, H.

W., & DeCapua, A.(2013). Making the transition to classroom

success: Culturally responsive teaching for struggling language

learners. University of Michigan Press.

Paradise,

R., & Rogoff, B. (2009). Side by side learning by observing and

pitching in: Cultural practices in support of learning. Ethos,

37, 102–138.

Paris, D.,

& Alim, H. S. (Eds.). (2017). Culturally sustaining

pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world.

Teachers College Press.

Rogoff, B.

(2014). Learning by observing and pitching in to family and community: An

orientation. Human Development, 57(2–3), 69–81.

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Westview Press.

Helaine W.

Marshall, PhD, is professor of education

and director of language education programs at Long Island University Hudson

Campus, where she teaches courses in TESOL and multicultural education,

primarily online, using the Synchronous

Online Flipped Learning Approach. Her research

interests include leveraging instructional technology in education, culturally

responsive and sustaining education, and nontraditional approaches to grammar

instruction. Her most recent book, just published, is Meeting

the Needs of SLIFE: A Guide for Educators.