Teacher Research: Empowering Teachers To Empower Students

by Sonia Rocca

Blending reflective practice with systematic

inquiry, teacher researchers put their students in the spotlight and treat

their work as a meaningful data-informed way to understand student learning

beyond standardized tests’ results. Teacher research is student centered and

fosters empathic student-teacher relationships, because teachers feel more

connected to their students and students feel more valued by their teachers.

Blending reflective practice with systematic

inquiry, teacher researchers put their students in the spotlight and treat

their work as a meaningful data-informed way to understand student learning

beyond standardized tests’ results. Teacher research is student centered and

fosters empathic student-teacher relationships, because teachers feel more

connected to their students and students feel more valued by their teachers.

According to an Australian study (Edwards &

Burns, 2016), English language teachers who completed an action research course

as part of their professional development reported its considerable impact on

their teaching, their relationship with students, their motivation for

research, and their recognition from their professional communities.

Undertaking their own classroom research was a transformative experience for

these teachers, as they felt more confident about their teaching and more

connected to their students. They also felt more valued by their schools and

their sector. Whether or not they continued to be engaged with action research,

they developed a research ethos that has guided them in their professional

growth.

Yet, despite all these benefits and more, teacher

research faces challenges. It may be perceived as an additional burden, and,

furthermore, teachers might think that research is for academics. For teacher

research to have a sustainable impact, it needs to be encouraged, mentored, and

incentivized. In this article, I discuss how teacher research contributes to

the development of teacher identity, agency, and voice. I also make a case for

mentoring teachers to cultivate a research mindset, emphasizing the importance

of supporting teacher research institutionally and beyond.

Yet, despite all these benefits and more, teacher

research faces challenges. It may be perceived as an additional burden, and,

furthermore, teachers might think that research is for academics. For teacher

research to have a sustainable impact, it needs to be encouraged, mentored, and

incentivized. In this article, I discuss how teacher research contributes to

the development of teacher identity, agency, and voice. I also make a case for

mentoring teachers to cultivate a research mindset, emphasizing the importance

of supporting teacher research institutionally and beyond.

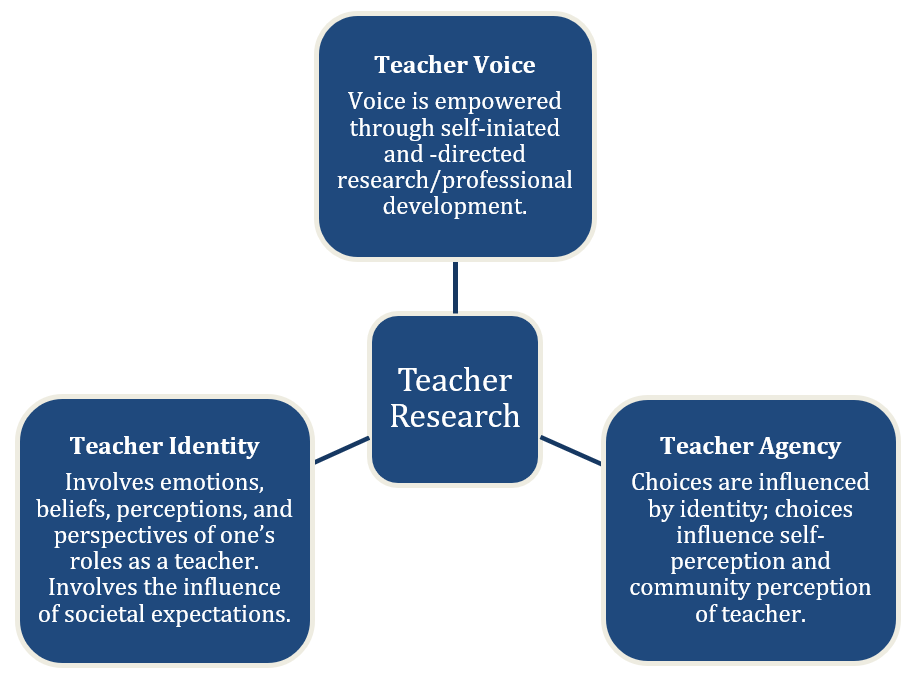

Teacher Identity, Agency, and Voice Are Interrelated

Teacher

Identity

Teacher identity is a multifaceted construct that

changes over time and across contexts. Its definition is complex, lying at the

crossroads of several disciplines—education, philosophy, psychology, sociology,

and anthropology. Barkhuizen (2017) defines language teacher identities as

“both inside the teacher and outside in the social, material and technological

world” (p. 4).

Teacher

Agency

Teacher agency is pivotal to the development of

teacher identity. The roles one fulfills as a teacher align with what one does

and how one acts as a teacher.

Teacher

Voice

Teacher voice relates to teacher identity and

agency in terms of the “who I am” as a teacher, the “what I do” as a teacher,

and the degree to which a teacher’s perspectives and experiences are shared and

valued. As they take on the role of researchers, the agency they show helps

shape their professional identity. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Interconnection of teacher identity,

voice, and agency as a result of teacher research. (Click here to enlarge.)

I have been a teacher-researcher for as long as I

can remember. I have always been interested in investigating what goes on in my

classrooms. This is the cornerstone of my professional identity. In 2012, my

sixth-grade class was involved in a 1:1 iPad pilot program. I designed a study

to test the effectiveness of such a program (agency). Not only did I share my

findings with colleagues, parents, and administrators, I also presented at international

conferences and published them in a refereed journal (voice). This whole

experience impacted not only my pedagogical practices, but also, importantly,

the way I see myself and present myself as a teacher (identity).

Mentoring Teacher Researchers

I am one of those teachers who merge teaching with

research, embedding inquiry into daily classroom practices and treating student

work as a constant source of data. In my constructivist approach to education,

I espouse Dewey’s (1933) view that inquiry is central to education. Inquiry is

propelled by reflective thinking, and “reflection includes observation” (p.

102), making it part of a scientific approach, where data represents observed

facts (p. 104).

An Important Distinction: Teacher

Research vs. Action Research

My experience as a teacher researcher has made me

appreciate what an endeavor it is to undertake classroom research. Where and

how to begin is always an issue. The idea of conducting action research can be

particularly anxiety-inducing because it focuses on implementing change. But

not all teacher research is action research. In fact, teacher research that is

exploratory research could be a good starting point.

Getting

Started

Smith (2020) recommends teachers start by

reflecting on a success, a problem, or a puzzle by sharing their recent

experiences with other colleagues or writing them down in a journal. Teacher

journals come in many different shapes and forms. The internet is a cornucopia

of such resources: teacher journal templates, ideas prompts, examples,

notebooks. A personal favorite is the Notes app:

I use it to jot down my thoughts, take photos or videos of my students’ work,

and record my observations. Writing journal entries is the stock-in-trade of

the typical reflective practitioner. It helps with monitoring practices,

sampling student work, scrutinizing patterns, and developing a research focus.

However, unless a teacher has a solid background in research methodology,

moving from reflective practice to systematic inquiry could be a daunting

endeavor.

Teacher Research

Mentors

This is where a research mentor comes in handy. A

mentor does not judge or tell you what to do, but rather encourages you to find

your own way. Mentors build on confidence and confidentiality to provide support

throughout the process, as mentees evolve from reflective practitioners to

teacher researchers. Mentoring helps structure reflective practice, which is a

common part of many educators’ teaching and is often included in teacher

evaluations, steering it toward systematic inquiry.

Mentors provide guidance in designing a research

methodology, from formulating research questions to collecting data and

analyzing them, using strategies like the following:

- dialog journals

-

classroom observations

-

Socratic questioning

-

scaffolding activities

-

interactive workshops

Mentors also assist with sharing findings through

presentations and publications. Smith (2020) is an excellent resource for

mentors, with practical guidelines based on the extensive experience of the

author as a research mentor and a coordinator of research mentoring

programs.

Incentivizing Teacher Researchers

Teacher research requires a considerable investment

of time and effort. It hinges on teacher agency and, hence, on the choice of

the individual teacher to engage in this type of professional growth. As such,

teacher research should be promoted but not mandated; it is important, too, for

teachers to see tangible signs of institutional support. Here are a few ways

institutions can incentivize teacher research within their staff:

-

Recruit “resident mentors” as part of your

professional development offerings. This could be a powerful motivator as

mentors advocate and pave the way for teacher research.

-

Provide opportunities for promotion for teacher

researchers.

-

Allot time for teacher research in professional

development credit hours or in a workload schedule.

-

School districts could organize action research

courses.

Promoting teacher research needn’t be limited to

institutions; professional organizations could offer grants to encourage

teachers to attend action research courses, as well as to present at

conferences and write for publication. The British Council has successfully

implemented “Action

Research Mentoring Schemes” in Latin America and South Asia.

In the End: Cui Bono?

All stakeholders benefit from teacher

research—teachers, students, parents, and administrators—and benefits stem from

both the process and the outcome. During classroom research, teachers build evidence-based

knowledge that informs their practices and refines their expertise, and they

become more attuned to student perspectives. Students feel their output is

important because it becomes input for a teacher researcher’s investigation.

All of this (the new knowledge, refined expertise, and improved student

self-perception) impacts the classroom environment and student learning, and it

can also impact policy making and curricular decisions. In Suskind’s (2016)

words, “teacher researchers are innovators, curriculum drivers, agents of

school change, and directors of their own professional development.”

References

Barkhuizen, G. (2017). Language teacher identity

research: An introduction. In G. Barkhuizen (Ed.), Reflections on

language teacher identity research (pp. 1–11). Routledge.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think, a

restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative

process. Heath.

Edwards, E. & Burns, A. (2016). Language

teacher action research: Achieving sustainability. ELT Journal,

70(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccv060

Smith, R. (2020). Mentoring teachers to

research their classrooms: A practical guide. British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/Mentoring_Teachers_Research_classrooms_handbook.pdf

Suskind, D. (2016, January 26). Teacher

as researcher: The ultimate professional development. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/reacher-researcher-ultimate-professional-development-dorothy-suskind

Sonia

Rocca is a Fulbright Global Scholar and an

English language specialist with the U.S. Department of State. She holds a PhD

in applied linguistics from University of Edinburgh and has been a language

educator for 30 years, teaching three different languages (English, French,

Italian) in three different countries (Italy, Britain, United States).

Currently, she teaches Italian at the Lycée Français de New York. Last year,

she launched a teacher research mentorship program at her

school.