|

One evening in 2018, I wrapped up my homework for a

vocabulary-focused MA course and fired up Netflix for a little comfort food in

the form of Star Trek. As I listened to the famous

opening monologue (“Space: the final frontier”), I suddenly wondered:

Was this TV show responsible for introducing the phrase “final frontier” into

American English?

One evening in 2018, I wrapped up my homework for a

vocabulary-focused MA course and fired up Netflix for a little comfort food in

the form of Star Trek. As I listened to the famous

opening monologue (“Space: the final frontier”), I suddenly wondered:

Was this TV show responsible for introducing the phrase “final frontier” into

American English?

Culture: The Final

Frontier

Corpus

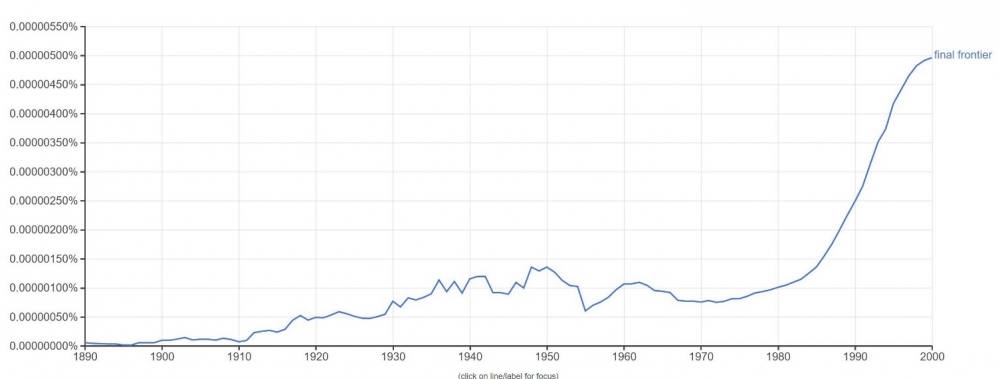

research demonstrated that the 1966 version of Star Trek

was, in fact, one of the earliest documented instances of that collocation.

Judging by Google Books, its usage has soared since Star Trek premiered: the phrase “final frontier” became 500% more popular

between 1960 and 2000 (Figure 1). Intriguingly, all pre-1960s instances of

“final frontier” that I found used frontier in the sense

of border. However, 21st-century matching strings for

“final frontier” almost exclusively refer to outer space. In short, Star Trek’s definition for “final frontier” has replaced

all other potential meanings.

Figure 1.

Google Books Ngram Viewer,

“final

frontier,” 1890–2000.

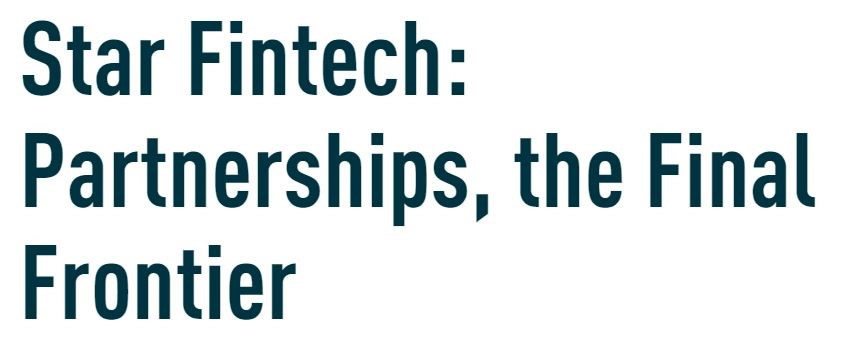

Digging

deeper, I noticed that the pattern of “NOUN, the final frontier” could be found

in unexpected places: financial headlines, websites unrelated to Star

Trek, and even academic journals (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Headline from a financial blog. (Pocard,

2016)

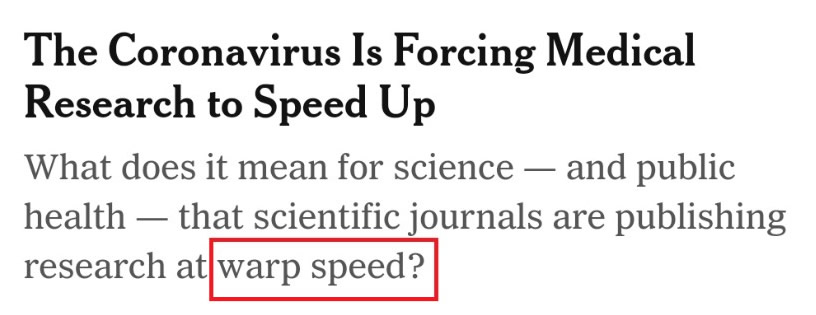

“Final

frontier” wasn’t alone, either: phrases such as “warp speed” and “beam up”

appear everywhere from pot roast recipes to serious news articles (see Figure

3).

Figure 3. Home

page of NYTimes.com, 25 April 2020. (Tingley, 2020)

Would an

English language learner understand those texts, if they were unfamiliar with Star Trek? Probably not without support.

When Words and

Collocations Become Idioms

Though Star Trek was where I began my research, there are dozens

of works of fiction that have introduced new words and collocations to the

English language. Consider the following list of terms coined within the past

50 years:

|

Term |

Origin |

|

Bucket list

(n) |

Movie,

Bucket List (2008) |

|

Red pill

(v) |

Movie, The Matrix (1999) |

|

Macgyver

(v) |

TV show, MacGyver (1985-1994) |

|

Stan

(v) |

Song, “Stan”

(2000) |

|

Go darkside /

join the dark side (v) |

Movie series, Star Wars (1977-2019) |

Looking

further back in history, you can find an even greater variety of such phrases,

including:

|

Term |

Origin |

|

Chase a white

whale |

Book, Moby Dick (1851) |

|

Albatross around

my neck |

Poem, “The Rime

of the Ancient Mariner” (1798) |

|

Down the rabbit

hole |

Book, Alice in Wonderland (1865) |

|

We’re not in

Kansas anymore |

Movie, Wizard of Oz (1939) |

In every

case, the influence of these phrases goes well beyond the original context for

which they were coined. In short, these phrases have become idioms. English

users who aren’t familiar with them are likely to get lost in certain discourse

spaces, especially online. Sooner or later, every student of English will

encounter one of these—and when they do, neither textbooks nor dictionaries

will help them understand.

So, how can

teachers introduce these to our students?

Suggested Classroom

Activities

1. Watch Clips

Together

Use of authentic media,

including films and TV shows, is already popular as a listening exercise.

Albiladi et al. (2018) have also shown that learners perceive American movies

as a valuable source of both cultural knowledge and new vocabulary. The caveat

is, of course, that movies aren’t designed for pedagogical purposes, so

teachers must support learners’ understanding of them.

With a bit

of preparation, even a clip that uses advanced vocabulary can be a fun addition

to a course. I like to start the semester by asking students whether they

already enjoy English-language media, and if so, what types? In the process,

I’ve discovered secret fans of everything from Fight Club to Dallas. After getting a sense of the crowd’s

preferences, I can find appropriate clips that they will appreciate. With a bit

of preparation, even a clip that uses advanced vocabulary can be a fun addition

to a course. I like to start the semester by asking students whether they

already enjoy English-language media, and if so, what types? In the process,

I’ve discovered secret fans of everything from Fight Club to Dallas. After getting a sense of the crowd’s

preferences, I can find appropriate clips that they will appreciate.

For example,

one group expressed interest in knowing “what movies all Americans would know.”

Realizing that six lines on the American Film Institute’s 100

Years…100 Quotes list come from Casablanca, I decided to teach the film’s final 6 minutes.

The worksheet I created (Appendix) activated students’ schema about World War

II. Then, the group watched the scene and worked together to figure out the

meanings of lines like “we’ll always have Paris,” “round up the usual

suspects,” and “this could be the beginning of a beautiful friendship.” We

finished the class by imagining conversational situations in which one of these

lines might come up. The funniest part was the following week, when some

students were late returning from break, and another student said, “I’ll round

up the usual suspects!”

A similar

lesson, or series of lessons, could be used to introduce the meaning of many

idioms on our list, such as “we’re not in Kansas anymore” or

“macgyver.”

2. Critically

Examine a Phrase’s Origins

Sometimes, the current

meaning of a phrase is quite far removed from the context in which it was

coined. In this case, awareness of the concept underlying the metaphor is more

important than knowing the source.

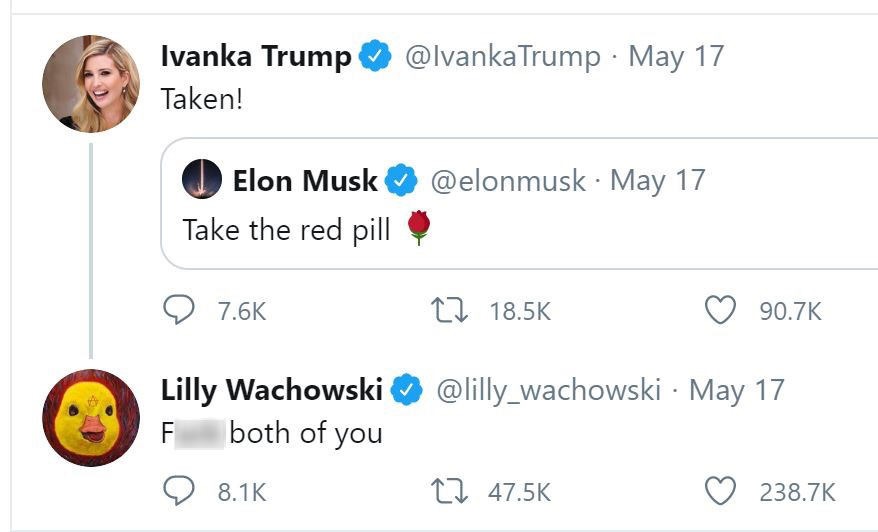

“The red

pill,” for example, entered the language as a reference to The

Matrix (1999), in which a man living inside a simulation breaks out

into the real world. The phrase “red pill” came to mean “opening your eyes to a

fact you’ve been ignoring.” In May 2020, however, Elon Musk tweeted “Take the

red pill” and got cursed at by the screenwriter of The

Matrix.

Figure 4: Lilly Wachowski replies to Ivanka Trump

and Elon Musk, 17 May 2020 (Pulver, 2020). NOTE: This image has been modified to censor possibly offensive language.

Even people

who have seen The Matrix might not be able to guess why

quoting the movie infuriated its screenwriter. Online, as it turns out, the

phrase “red pill” has been coopted by several movements with whom Ms. Wachowski

disagrees. The Men’s Rights Movement, for instance, uses it to mean “realizing

that feminists are secretly oppressing men.” Among alt-righters, it can refer

more generally to opposing government action. In Mr. Musk’s case, he was

apparently suggesting that Americans should defy public health orders and

reopen businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic (Pulver, 2020).

Learners who

practice their English online may encounter these darker meanings of “red pill”

long before they learn its more innocuous meaning. A teacher can help by

introducing the phrase’s origins and its evolution at the same time. For

example:

-

Watching the original

scene

-

Predicting

what “take the red pill” means based on its origin

-

Checking predictions

against the four different definitions provided by UrbanDictionary.com

(assuming, of course, that your audience is comfortable with user-provided definitions

which may use harsh language)

-

Discussing how the first

meaning led to the others

-

Reading articles about

online communities who call themselves “Red Pillers” and debating their

significance

This type of

discussion could be used for many other phrases that mean something different

online than off. For instance, depending on the context, “down a rabbit hole”

can mean discovering something unexpected, becoming obsessed with a new hobby,

or being swallowed up by a conspiracy theory. The relationships among those

definitions could spark a fascinating classroom conversation with advanced

students.

3. Work With Text

Types

Finally, one can combine a

cultural vocabulary lesson with a lesson on text types. Byrne & Jones

(2018) have pointed out that the verbal captain’s logs delivered throughout

each Star Trek episode are “more than an expository

device…[they] require the Captain to conduct self-analysis.” In other words,

Captain Kirk demonstrates reflective self-talk. As many learning journals and

assignment reflections prove, some students struggle to get started with that

process.

In my

intensive English program, every student must assemble a semester portfolio of

eight to 12 assignments and write reflections for each one. In the past,

students have asked why they can’t simply post their assignment and their

grade. So, I decided to explicitly teach the reflection format, usingStar Trek. This spring, I developed a lesson plan based

around clips from theepisodes “The

Man Trap” and “Arena.”

(Both episodes are available through subscription on Netflix and CBS All

Access.) The sequence was as follows.

-

Elicit meaning of the words

“blog” and “log in.” Ask students to predict what “log” originally meant. Guide

them to “a record of everything that happens.”

-

Introduce the basic format

of a log: date, what happened, why it happened, what’s next.

-

Activate knowledge about

sci-fi. Point out that the genre uses some made-up words (e.g., technobabble).

-

Preteach the technobabble for Clip 1.

-

Have students watch Clip 1

and answer: What happened? Why? What’s next? (Repeat as necessary.)

-

Between clips, discuss why

a log is an important TV narrative device: It helps the audience catch up if

they missed a scene. Connect this with how they can explain their work to an

outside grader.

After five

clips, we progressed to writing a captain’s log about something we each did

that day. In a follow-up lesson, we translated our three questions into

questions you can ask about any project:

-

What

happened ⇨ What went well? What didn’t go well?

-

Why

⇨ What skills did I use? Which ones need more practice?

-

What’s

next ⇨ How can I do better on the next assignment?

Finally, we

used this format as a guideline for writing assignment reflections for their

end-of-semester portfolios. I noted that, despite the midsemester switch to an

online format, there were fewer questions about how to write a reflection or

why reflections are useful.

Conclusion

Because

English-language media have contributed idioms to the English language, English

learners need to be exposed to influential media artifacts. Using movies and TV

to teach vocabulary is an enriching and fun addition to a standard English

language curriculum.

References

Albiladi, W.

S., Abdeen, F. H., & Lincoln, F. (2018). Learning English through

movies: Adult English language learners’ perceptions. Theory and

Practice in Language Studies, 8(12), 1567–1574. http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0812.01

Byrne, A.,

& Jones, M. (2018). Worlds turned back to front: The politics of the

mirror universe in Doctor Who and Star Trek. Journal of Popular

Television, 6(2), 257–270. http://dx.doi.org/10.1386/jptv.6.2.257_1

Pocard, N.

(2016, November 9). Star Fintech: Partnerships, the final frontier. Finextra. https://www.finextra.com/blogposting/13350/star-fintech-partnerships-the-final-frontier

Pulver, A.

(2020, May 18). Lilly Wachowski rounds on Ivanka Trump and Elon Musk over

Matrix tweets. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/may/18/lilly-wachowski-ivana-trump-elon-musk-twitter-red-pill-the-matrix-tweets

Tingley, K. (2020, April 21).

Coronavirus is forcing medical research to speed up. The New York

Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/21/magazine/coronavirus-scientific-journals-research.html

Claire

Fisher is a longtime nerd whose love for

language overlaps with her love for books, movies, and television. She has

taught ESOL in Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York and received a master’s

degree in TESOL at The New School in 2019. |