Almost 20 years ago, Nunan (1999) called listening “a Cinderella skill in second language learning” (as cited in Ahour & Bargool, 2015), but it still has not been given as much attention as other major skills. For example, at the TESOL 2018 International Convention, there were only 14 sessions out of more than 800 that focused on listening. English language learners spend much time in class completing tasks such as writing five-paragraph essays and conjugating verbs, but in a typical American university or at work, they spend most of their time listening (Emanuel et al., 2008; Janusik, n.d) and analyzing the aural material. Not prepared for real-life listening comprehension, English language learners often feel frustrated when confronted with authentic English (Gebhard, 2012; Sherry, Thomas, & Chui, 2010) and do not perform their best simply because they do not understand the native English speakers with whom they interact and do not have experience listening to authentic English for an extended period of time. This article introduces two listening strategies, including example activities, that can be used for any level and easily modified to suit your particular teaching context.

Almost 20 years ago, Nunan (1999) called listening “a Cinderella skill in second language learning” (as cited in Ahour & Bargool, 2015), but it still has not been given as much attention as other major skills. For example, at the TESOL 2018 International Convention, there were only 14 sessions out of more than 800 that focused on listening. English language learners spend much time in class completing tasks such as writing five-paragraph essays and conjugating verbs, but in a typical American university or at work, they spend most of their time listening (Emanuel et al., 2008; Janusik, n.d) and analyzing the aural material. Not prepared for real-life listening comprehension, English language learners often feel frustrated when confronted with authentic English (Gebhard, 2012; Sherry, Thomas, & Chui, 2010) and do not perform their best simply because they do not understand the native English speakers with whom they interact and do not have experience listening to authentic English for an extended period of time. This article introduces two listening strategies, including example activities, that can be used for any level and easily modified to suit your particular teaching context.

Strategy 1: Demonstrate the Difference Between Hearing and Listening

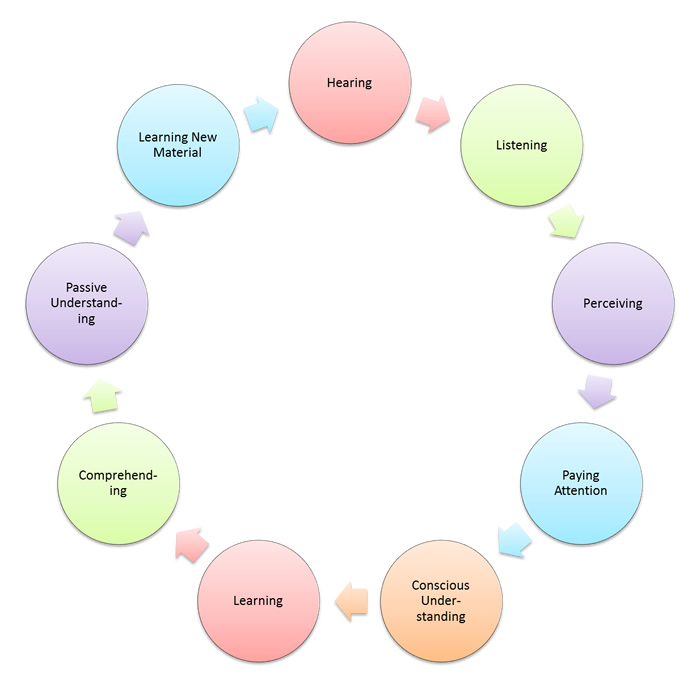

Hearing and listening are different processes. Some students, usually beginners, easily give up listening to a text in English, thinking that their listening skills have not been developed well enough to understand it. On the other hand, intermediate and advanced learners could be overconfident in assuming that they do not need to practice complex academic listening because they already understand movies and everyday English. Show your students the difference between hearing and listening with the help of the following chart (Figure 1) and activities.

Figure 1. The cycle of listening (click here to enlarge)

The cycle of listening includes:

-

Hearing: being aware of a sound

-

Listening: concentrating on what is heard

-

Perceiving: distinguishing sounds and words

-

Paying Attention: consciously focusing on aural material

-

Conscious Understanding: identifying aural material without an extra effort

-

Learning: getting new information from aural material

-

Comprehending: understanding received aural material

-

Passive Understanding: comprehending aural material without making an effort.

-

Learning New Material: receiving new information from aural material

For Beginner and Low-Intermediate Students

Beginner and low-intermediate students need to build confidence distinguishing hearing from listening. To demonstrate:

-

Play a brief audio clip in a foreign language that your students do not speak. Tell them that they can hear the words but will not understand them. This is an example of passive listening: Students can hear the sound, but won’t distinguish the words. They are not learning the language they have heard and are not expected to understand the words.

-

Play a brief audio clip or read a short text in English. Make sure the aural material contains words that students have learned. For example, if you are teaching a beginner level for children, read aloud a simple sentence: “I have a pet.” This is active listening. Students should be able to recognize the words.

-

Provide students with the following table and ask them to circle a word they heard:

father

pet

monkey

-

Now play a recording or, if your classroom does not have technical resources, read a text containing the original sentence and other sentences. For example, if you teach young children, you could play the song, “I Have a Pet.”

I Have a Pet

LyricsDo you have a pet?

Yes, I have a dog.

I have a pet.

He is a dog.

And he says, “Woof, woof, woof, woof, woof. Woof woof.”

I have a cat.

I have a pet.

She is a cat.

And she says, “Meow, meow, meow, meow, meow. Meow meow.”

I have a mouse.

I have a pet.

He is a mouse.

And he says, “Squeak, squeak, squeak, squeak, squeak. Squeak squeak.”

Woof woof.

Meow meow.

Squeak squeak.

I have a bird.

I have a pet.

He is a bird.

And he says, “Tweet, tweet, tweet, tweet, tweet. Tweet tweet.”

I have a fish.

I have a pet.

She is a fish.

And she says, “Glub, glub, glub, glub, glub. Glub glub.”

I have a lion.

A lion?!

I have a pet.

He is a lion.

And he says, “Roar, roar, roar, roar, roar. Roar roar.”

Tweet tweet.

Glub glub.

ROAR! -

Ask your students to count how many times they heard the word pet in the song. This is a close listening task. Students are not just hearing the words in the lyrics, they are perceiving the text and paying attention, which leads to conscious understanding, learning, comprehending, passive understanding, and then, again, to hearing new material.

-

Ask your students to make a list of all the words they recognized. The goal of the task is to show students that they can understand aural material even if it is not read by their instructor.

For Intermediate Students

-

Ask your students to pick any song in English they enjoy listening to.

-

Find that song on YouTube. You may want to double check that the song and its video are class and level appropriate.

-

Play one line of the song. Pause. Ask students (one by one or as a group) to say what they heard. Your students may ask you to play the same line several times.

-

Find another YouTube video of the same song, but this time with captioned lyrics. Play the same line again and allow students to see the lyrics.

-

Discuss the vocabulary if needed.

-

Next, play the same part of the song again, but do not show the lyrics. Check if students can clearly hear the words in the song.

-

Repeat the first line of the song and, without pausing, play the next line. Pause. Repeat Steps 3 and 6. Play again from the beginning. It is important to start playing the song from the very beginning. Students will complete a full cycle of listening (from hearing to learning new material) and will unconsciously realize that their listening comprehension is getting better with every repeated line.

If your students do not enjoy music, play a clip from a movie or read a text that can resonate with your class. It is important to find aural material that has some meaning to students. If they find it boring or useless, students will be less likely to participate in such an activity.

For High-Intermediate and Advanced Students

High-intermediate and advanced students tend to pay more attention to academic writing than listening, thinking that they do not need to continue practicing listening because they can understand everyday English.

60-Second-Science Scientific American podcasts will encourage your students to improve without taking much of your class time. Play a 60-second audio clip from the Scientific American website and ask your students to show how much they understood in the short aural segment. Students could show a number of fingers with five meaning “That was easy! I understood it perfectly and can retell using all the details” and one meaning “I did not understand this podcast at all.” It is important to explain to your class that students will not be graded for the number they assign to their listening comprehension, or the students’ answers may not reflect reality. Try to create a comfortable class atmosphere where students will not be ashamed to admit that their listening was not perfect.

Depending on the self-assessments, either ask students to partner up and retell the main idea of the 1-minute podcast or play the audio again and ask your students to record the keywords. Using the keywords provided by students, help your class to break the information into chunks and retell the material. Scientific podcasts are created for native English speakers and usually are challenging for even advanced language learners. By practicing every day (remember, the podcasts are only 60 seconds!) the students can improve their listening comprehension by perceiving the information and paying attention to it.

Strategy 2: Teach a Variety of Common Speech Markers

Knowing the most typical phrases that professors use in their lectures will help your students stay focused and understand the organizational pattern of a class.

How to Teach It

Introduce students to a basic list of discourse markers, also called cues, that demonstrate the structure of any speech. Ask students to come up with a list of phrases that a teacher uses to introduce a topic, to give a definition, finish a lecture, provide an example, emphasize the material, etc. Do not introduce all cue markers at once. Ask your students to listen to the material and pay attention to the markers and information that follows it. Play a university lecture and focus on the material provided after these cues.

Common Speech Markers

Cues for Introduction

-

Let’s start

-

Today’s class is

-

The topic is

-

The purpose of this lecture is

Cues for Definitions

-

The definition of ...is

-

It can be defined as

-

It means

-

It is known as

Cues for Sequence

-

First

-

Next

-

After

-

Another

How to Adapt to Your Level

There are sequence markers for giving examples, conclusions, repetitions, and so on. It is easy to create your own chart of cues: Just pretend you are teaching a class and would like to emphasize a topic or introduce a list. You could also ask your students to make a list of discourse markers in a small group activity.

Why are discourse markers important? They are easy to understand and recognize, and they can serve as traffic lights in a difficult lecture. Listening to a challenging speech for a particular task, such as a definition or a sequence, will be easy with the help of these sequence markers.

There are a lot of listening techniques that improve the listening comprehension of students. If instructors demonstrate the difference between hearing and listening and practice close listening activities, students will improve their listening comprehension and will be encouraged to continue practicing and improving.

References

Ahour, T., & Bargool, S. (2015). A comparative study on the effects of while listening note taking and post listening summary writing on Iranian EFL learners’ listening comprehension. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 5(11), 2327–2332.

Emanuel, R., Adams, J., Baker, K., Daufin, E. K., Ellington, C., Fitts, E.,… Okeowo, D. (2008). How college students spend their time communicating. International Journal of Listening, 22(1), 13–28.

Gebhard, J. G., (2012). International students' adjustment problems and behaviors. Journal of International Students, 2(2), 184–193.

Janusik, L. (n.d.). Listening facts. Retrieved from http://www.paragonresources.com/library/listen.pdf

Sherry, M., Thomas, P., & Chui, W. (2010). International students: A vulnerable student population. Higher Education, 60(1), 33–46.

|

Download this article (PDF) |

Olga Uzun is a North Carolina State University Intensive English Program lead instructor for listening and note-taking. Not an English native speaker she, like many of her students, struggled with ESL listening comprehension in the past. A regular presenter at professional conferences, Olga is interested not only in listening but also in ways to improve the ways we teach grammar and reading comprehension.