|

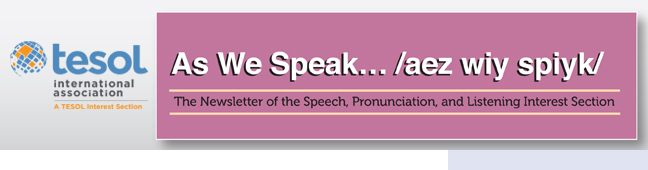

Assessing progress in pronunciation can be very challenging.

How can teachers tell if a student is progressing with his or her

pronunciation? Celce-Murcia, Brinton, and Goodwin (2010) believe that

the teacher needs to provide ongoing informal feedback on individual

progress to support each learner during instruction. They consider this

to be a key issue in the teaching of pronunciation. In addition, many

prominent practitioners (Acton, 1984; Miller, 2001) believe that

students should be involved in evaluating their own progress. Should

pronunciation instructors use and integrate this knowledge to test and

track pronunciation progress?

One of the challenges we face in assisting students with their

pronunciation is helping them “see” the progress they are making. This

can be a daunting task because speech is typically an auditory task and

it is difficult to provide a visual representation of auditory

information. If we can find ways to do this, students will have concrete

visual methods for measuring their pronunciation progress and success.

MULTIPLE METHODS

It seems crucial to integrate the underlying pronunciation

principles of the research above into our tracking methods to make them

more efficient and effective. To create a solid foundation, we must

attempt to utilize students’ self-monitoring and teachers’ continuous

feedback for successfully tracking student progress in pronunciation.

Some effective and efficient methods of tracking pronunciation progress

utilize a variety of formats: written, oral, audio, recordings,

software, and other technology.

We need to assess students’ current levels to create a baseline

of their pronunciation and to help them construct a clear vision to

achieve their personal goals. It is important to keep in mind both

expressive (their ability to actually say the words or use pronunciation

features) and receptive (their ability to understand the different

features and discriminate between them) speaking skills.

DIAGNOSTIC DECISIONS: EXPRESSIVE AND RECEPTIVE PRONUNCIATION

Looking at students’ ability to produce speech, we need to make

numerous decisions and consider different speaking styles that can be

used. Practices that have been used for assessment and tracking include

imitative, prearranged, spontaneous, and self-monitored speech. Each of

these practices has its own inherent pros and cons.

Examples of Styles

Imitation. The student imitates the

examiner’s speech. This produces results that focus more on the ability

of the student to correctly repeat a given stimuli than the typical

speech productions they use independently.

Prearranged. The student is examined and

prompted on a specific and possibly limited corpus of tasks. This may be

a reading task in which spelling can influence pronunciation or create a

narrow testing scope.

Spontaneous. The student is assessed based

on more natural and unplanned speaking tasks. This may not lead to all

the target sounds being produced and may not provide a comprehensive

enough picture.

Self-Monitored. The student completes

speaking tasks in which he or she can engage in self-analysis before the

task is completed or submitted. Students may make changes to their

speech sample before the examiner has an opportunity to observe the

typical patterns they are using.

We also need to decide if we utilize assessment tools that

specifically look at just sounds/phonemes, words, sentences, or

connected speech, or a combination of all of these.

The pronunciation teacher can create a profile for each student

based on assessment results. This profile may include a visual

representation of the student’s skills in concrete terms (test scores or

numbers) for the selected receptive pronunciation features. In

addition, it may list specific sounds/phonemes that a student had

difficulty with during the assessment. An overall test score can be

compared to the total possible score. This will help students actually

see their starting points by comparing the numbers of their

pronunciation performance to the total possible number they could

achieve. Consider including the following components: consonant

production, consonant discrimination, vowel production, vowel

discrimination, syllables, word stress, sentence stress, focus words,

thought groups, connected speech, and

intonation.

MEASURING “TALKING” SUCCESS

Measuring a student’s progress is not easy. Nevertheless, if

students acknowledge some of their strengths and choose specific targets

to work on, it will help create a visual representation of their

individual goals and establish a starting point to track their success.

The pronunciation teacher can consider whether or not the

pronunciation textbook he or she is using has an assessment piece that

accompanies it, such as Clear Speech by Judy B.

Gilbert (2007) or Targeting Pronunciation by Sue

Miller (2008).

Teachers can also create their own pronunciation profile forms

to go along with these assessments. These forms should integrate both

receptive and expressive pronunciation components, along with the

ability to retest and write the scores or information two times after

the initial baseline testing, creating pre- and posttest capability.

This will yield valuable data regardless of the length of time students

participate in pronunciation classes. It is important to have the

students choose their own goals or target areas after reviewing the

results on their profiles because they have to work toward achieving

these goals and it is in the teachers’ best interest that they be highly

motivated.

SELF-RECORDINGS

In addition to seeing the progress by looking at pronunciation

scores as we test and retest, we should also utilize the auditory

component. This can be achieved by having students record samples of

their speech in the first week of class before they start learning the

specific pronunciation techniques, and recording again in the last week

to compare the samples. The difference is often remarkable. Sometimes

more time is needed to hear a marked difference; still, it is useful to

utilize this technique as one of the many methods of tracking students’

progress.

Depending on the language level of the student, it is important

to consider the levels of complexity of the recording tasks (see Figure

1).

Figure 1. Recording Tasks’ Complexity

|

Lower Levels |

Upper Levels |

|

Short Introduction |

Detailed Introduction |

|

Basic Intonation Patterns |

Storytelling Picture Tasks |

|

Numbers |

Specific Open-ended Topics |

|

Reading One Paragraph |

Reading Multiple Paragraphs |

|

Short Sentences |

Connected Speech |

Teachers can share instructions with students on how they can

record themselves speaking using any of the following: personal

computers, language lab computers, campus PCs, smartphones, iPhones, tablets, and

iPads. Most computers have a sound recorder feature or students can

download a free voice recording program such as Audacity.com. After they

record their sample, they can save it as an MP3 or wav file and attach

it to an e-mail to their instructor or upload it to

Blackboard.

TRACKING METHODS

Methods used to track pronunciation progress include Blackboard

and software tracking, phone and computer recordings, pre/posttests,

and pronunciation logbooks.

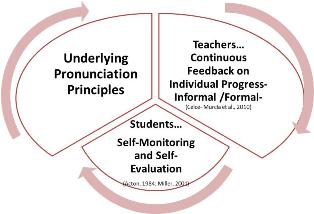

One way of tracking students’ pronunciation progress is

Blackboard. The instructor can provide specific Internet sites for the

students to practice their targets with links and descriptions for

students on Blackboard. I provide five to six sites. Each time they

practice on a site, the teacher is able to secretly track them and see

how often they are practicing and even which sites they are practicing

on most frequently. In Figure 2 you can see that the students accessed

the external links for practicing with pronunciation sites 279 times

during this 4-week time period.

Figure 2. General Blackboard Tracking

|

Folder |

Hits |

Percent |

|

Course Information |

44 |

10.26% |

|

Course Documents |

23 |

5.36% |

|

Assignments |

56 |

13.05% |

|

External Links |

279 |

65.03% |

|

Total |

429 |

100% |

The teacher can access the Blackboard tracking information by

clicking on Control Panel>Course Statistics>Select Report:

Accesses by Content Area>Time Period: your choice>Users:

select all users.

Teachers can track the number of times each student individually practices on each site by looking at the

external links column. In Figure 3, on the left you will see the

student’s initials and by following that row horizontally to “external

links” you can identify and track how many times that student practiced.

Note that the student with initials D.A. practiced 80 times and the

student with initials L.S. didn’t practice at all. Teachers can also

access charts that show the specific time of day and days of the week

the student practiced, as well as sites used by each student.

Figure 3. Blackboard Tracking of Individual Students

|

Course

Information |

Course

Documents |

Assignments |

External Links |

Total |

|

OB |

2 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

12 |

|

DB |

0 |

0 |

0 |

14 |

14 |

|

DA |

2 |

3 |

7 |

80 |

92 |

|

GD |

1 |

1 |

9 |

17 |

28 |

|

KY |

1 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

6 |

|

KE |

1 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

8 |

|

LS |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

|

LY |

2 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

9 |

|

CM |

7 |

1 |

2 |

12 |

22 |

|

NN |

0 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

|

NU |

6 |

4 |

5 |

7 |

22 |

|

JP |

2 |

2 |

2 |

9 |

15 |

|

PQ |

1 |

1 |

3 |

28 |

33 |

|

PD |

3 |

3 |

3 |

47 |

56 |

|

VI |

2 |

0 |

0 |

28 |

30 |

|

XP |

1 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

|

YH |

12 |

5 |

11 |

6 |

34 |

|

ZX |

0 |

0 |

1 |

8 |

9 |

|

Total |

44 |

23 |

56 |

279 |

429 |

When students are not progressing and we can see that they have

not practiced, we have evidence to show them why they might not be

progressing. We may want to recognize and positively reinforce the

individual students who are practicing. For example, I have posted

announcements on Blackboard congratulating those participating students

for their hard work and practice. It can make a significant

difference.

SOFTWARE TRACKING

Another method of tracking that can be utilized is

pronunciation software with tracking features. Many different kinds are

available. At our IEP, we have American

Speechsounds software in our language lab. With this program,

students track themselves by writing down results in a log during class

or during additional practice times while practicing specific

pronunciation exercises. They can also record their own voices and

compare themselves to the speech models using the important principle of

self-monitoring.

PRONUNCIATION LOGBOOK TRACKING

Some pronunciation textbooks, such as Sound

Concepts by Marnie Reed and Christina Michaud (2005), include

pronunciation logs so that students can track their errors based on

teacher feedback. Writing it down helps both students and instructors

see if there are any patterns as to the type of error

or frequency of error. As students begin to analyze

their individual and unique pronunciation patterns, they can begin to

make changes. This kind of insight or self-awareness seems to apply to

many skills we learn in life. For example, during class practice, one

student may notice that the teacher’s feedback focused on that student’s

difficulty using the /r/ sounds at the right time and the /l/ sound was

often used instead. Another student may learn that he or she

unintentionally adds vowels in places that they don’t exist (epenthesis)

like saying “bulue” instead of “blue,” and yet another student may gain

awareness that he or she deletes final consonants while speaking. A

pronunciation logbook can help each student by providing detailed

specific teacher feedback about his or her pronunciation and also aid in

the process of self-analysis. This allows students to see if there is a

pronunciation pattern of types and frequency used when they speak. My

students use this log as well as other logs that I have created that

emphasize specific pronunciation features such as stress, focus words,

thought groups, and American style intonation.

SHARING RESULTS

Results need to be shared to be effective. For students to

“see” progress accurately after testing, the results need to be

collective. Along with individual detailed profiles, we can create

general class profiles to share. This allows students to compare their

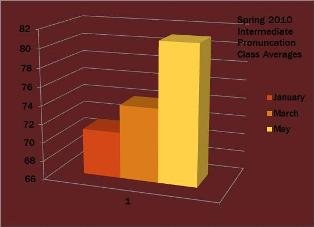

performance to an average (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Fall 2010, Intermediate Pronunciation, Class Averages

Pronunciation Test (Total Possible = 100 points)

August December

65.8% correct 82.5% correct

Implementing all these effective methods of tracking in

teaching contexts can help students succeed in learning pronunciation.

Which methods will you use to successfully track your students’

pronunciation progress?

RESOURCES: TEXTBOOKS FOR CLASSROOMS

Miller, S. F. (2007). Targeting

Pronunciation: Communicating Clearly in

English (2nd ed.). Thomson Place, Boston, MA:

Heinle.

Gilbert, J. B. (2008). Clear speech: Pronunciation and listening comprehension in North American

English. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Reed, M., and Michaud, C. (2005). Sound Concepts: An

Integrated Pronunciation Course. New York, NY:

McGraw-Hill.

REFERENCES

Acton, W. (1984). Changing fossilized pronunciation. TESOL Quarterly, 18(1),

71-85.

Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D., & Goodwin, J. (2010). Teaching Pronunciation: A Course Book and

Reference Guide (2nd ed.). Cambridge,

England: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, S. (2001).

Self-monitoring, self-help, and the route to intelligible speech. The CATESOL Journal, 13(1), 173-182.

Catherine Moore M.A.CCC-SLP is honored to be a faculty

member for the American Language Program at California State

University, Fullerton. She is a licensed Speech Pathologist with a

Certification in Clinical Competence awarded by the American Speech

Language Hearing Association. Catherine has presented internationally in

Cambodia as a People to People Ambassador and most recently was invited

to speak in Sao Paulo, Brazil. |