|

Benefits and Limitations of Textbook Activities

Textbooks are a valuable item in the ESL teacher’s toolkit. They provide a well-thought-out curriculum to follow that has been designed by experts in the field. They also offer a variety of activities, which is especially true of comprehensive, four-skills textbooks. Finally, they include interesting topics for reading, listening, and discussion with exciting visuals to engage students.

That said, there are major limitations to textbooks. Perhaps the most notable is a result of publishing practicalities. Page requirements may limit the number and complexity of activities. Similarly, the cost of paying curriculum designers can prohibit adding more than the minimum number of activities. These limitations are especially reflected in speaking activities, where repetition and output are so important for learning the language.

Why Expand Textbook Activities?

While it is tempting to simply move through the textbook and complete activities as-is, students likely will not get maximum benefit. Instead, teachers can use textbook activities as a base from which to expand and make output more meaningful, get students producing more output, and provide more repetition of the target language.

Using language for meaningful, productive purposes plays a very important role in learning the language. Due to textbook limitations, output can be less meaningful than it should be. For example, textbooks often include speaking tasks such as “Share X with a partner.” This is output, but not meaningful. Where is the incentive to listen? How will I know if my speech is comprehensible to my partner? How much practice will I really get by quickly relaying information? It is a one-sided task with no meaningful negotiation of meaning between speakers. Negotiation of meaning is an important part of output because it allows students to notice the gaps in their language knowledge, experiment with language they are learning, and think metalinguistically about their language (Nation & Newton, 2009). The more we can get our students producing this meaningful output, the better!

Meaningful output is not the only thing missing. When learning vocabulary, according to Folse (2004), “Research findings indicate that what is more important is not what you do with the word as much as how often you do this with the word. Frequency of retrieval is key” (p. 158). As a result, teachers should supplement textbooks by incorporating more opportunities for repetition into activities. Referring to the aforementioned “Share X with a partner” activity, this only allows each person to speak one time. How much retrieval is really going on with the target vocabulary or grammar structure?

Activity Example 1

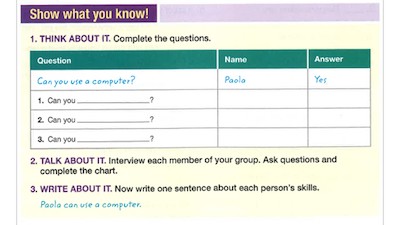

This activity comes from Future 4, 2nd Edition. It is a typical textbook speaking activity. First, notice how short the activity is. It only has three questions, so students are not doing much speaking. They will ask three questions to three people, which is not much output. In addition, if they write a different vocabulary phrase in each question, they are not getting any repetition to build fluency; they will ask the question, using the word or phrase one time, and move on.

The next issue is that this activity lacks purpose. It has some output, but it is not meaningful. For instance, consider part 3 of the activity. If I am a student, why am I writing one sentence about each person’s skills? This might be a good homework activity, but it is not the most meaningful, productive activity for the classroom. Why am I asking these questions? Why am I taking notes? How can we make this a more meaningful activity?

These typical textbook speaking activities can be expanded by turning them into a survey.

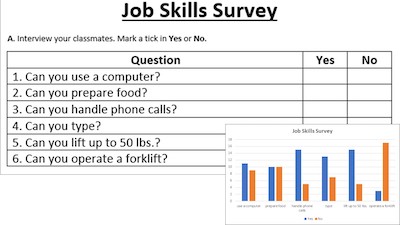

Here the textbook activity is turned into a simple survey. Surveys include more interaction in the form of repetition. Students are asking each question to each person in the class, so a class of 12 students means students will ask each question 12 times. This helps build fluency more than the basic activity by providing more retrieval of the target language.

Surveys are also meaningful. Students are not writing sentences without purpose; instead, they are collecting data about their class that can be used in a variety of ways. For instance, after collecting the data they can make a graph. Making and reading graphs are valuable skills, and surveys lead perfectly into them. In addition, creating a graph leads to more productive speaking activities, where students discuss trends or summarize information.

These types of activities are highly scaffoldable. You can create the survey yourself, create a gap-fill where students add some information, or have students create survey questions on their own. Similarly, graphs can be made individually or as a whole class.

For online classes, students can write their surveys on paper. Rather than mingling as a class, you can rotate students through breakout rooms. Finally, follow-up activities like making and analyzing graphs work great as asynchronous online work.

Activity Example 2

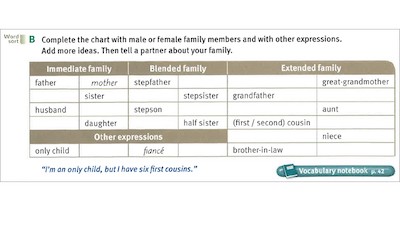

The next example is a vocabulary activity from Touchstone 3, 2nd Edition. This is a vocabulary activity in a unit about family and memories. Vocabulary words are introduced through a short reading, and then students complete the chart by adding the missing words for each pair. The activity culminates in a communicative activity where students are asked to “tell a partner about your family.”

One drawback to this activity is the lack of practice. Students write the words, but only use them one time when sharing. Students from small families will not use most of the words in their speaking.

This activity also lacks a meaningful purpose. Why am I telling my partner about my family? What incentive does my partner have to listen? This is a one-way activity, meaning information only flows in one direction. We can expand this to be more meaningful and provide repetition by adapting it into a two-way activity where students share information back and forth.

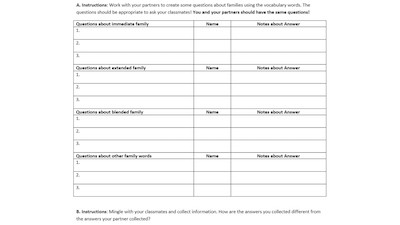

When activities lack discussion, have students make discussion questions themselves. In this example, students work in pairs to craft discussion questions using the target vocabulary. After writing the questions, the pair splits and each person gets paired with a new partner to interview. They ask and answer the questions, writing notes for later reference. Finally, students return to their original partners and compare answers. They asked the same questions to different people, so did they find anyone who answered the same? Did they find any surprising or different answers? At each stage of this expanded activity students are producing meaningful output and negotiating meaning.

The expanded activity provides more repetition. Students use more of the words and use them at all three stages of the activity. Students are also forced to use words they might not use if only describing their families.

Like the first example, this type of interview-compare activity can lead to many follow-ups, such as writing a paragraph about a classmate’s family or summarizing information.

This activity can be easily adapted to work online by using Google Docs and breakout rooms. The follow-up writing or analysis activities are ideal for asynchronous online work.

Activity Example 3

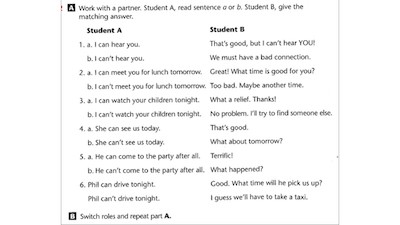

This final example activity comes from Well Said, 4th Edition. It’s part of a small lesson on how to reduce or stress “can” and “can’t” when speaking. Pronunciation is often relegated to call-out boxes or mini lessons, so expanding on these activities is vital.

This is a pair activity, where student A picks a phrase to say and student B listens and responds with the correct choice. One immediate issue here is that this activity is primarily reading, which may not lend itself to practicing spontaneous pronunciation that is needed in conversation. It also suffers from the same limitations we have seen regarding meaningful purpose and repetition. Reading and responding to canned phrases is not a particularly meaningful activity. In terms of repetition, with only six questions, students will have, at most, twelve opportunities to use the target language.

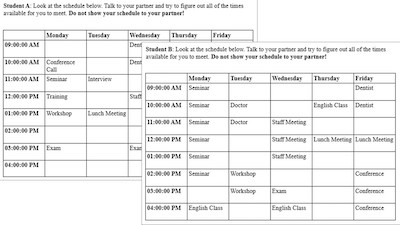

When textbooks provide these read-and-response activities, they can be expanded by creating jigsaw speaking tasks. Here, students each have a different calendar, and they need to ask and answer questions like “Can you meet on Monday morning at 9?” to find the times they are both free.

This expanded activity is more of a speaking activity than a reading one, lending itself to rehearsal of more natural, connected speech . The activity is also more meaningful, as negotiating schedules is a task that anyone who makes an appointment with a doctor or dentist must manage. It now also includes much more repetition, and repetition can be increased or decreased by changing the complexity of the schedules, such as the number of time blocks and/or days.

For online teaching, students can write their own schedules on paper, and breakout rooms are ideal for pair speaking activities.

Conclusion

Textbook activities are an excellent foundation, but teachers should expand them to incorporate more meaningful output and repetition.

When you look at a textbook activity, consider whether it gives enough opportunities for meaningful output. Find ways to turn one-way activities into two-way activities, where students are not simply communicating into a void, but communicating with a specific purpose in mind. Similarly, try to add connections to real-world tasks, such as collecting information for further discussion or analysis. Finally, always incorporate more repetition to increase the frequency of retrieval for the target language; adding stages or discussion questions to the task are great for increasing repetition.

References

Folse, K. S. (2004). Vocabulary myths: Applying second language research to classroom teaching. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Grant, L. (2017). Well Said, 4th Ed. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Lynn, S., Magy, R. & Salas-Isnardi, F. (2018). Future 4, 2nd Ed. Hoboken, NJ: Pearson Education.

McCarthy, M., McCarten, J. & Sandiford, H. (2014). Touchstone 3, 2nd Ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Nation, I. S. P., & Newton, J. (2009). Teaching esl/efl listening and speaking. New York, NY: Routledge.

Brad Knieriem is an ESL instructor and Intensive Program Coordinator at Howard Community College. He has a MA in Applied Linguistics from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, and has been teaching ESL/EFL domestically and abroad for over 10 years. |