|

Introduction

Intonation (using voice pitch to communicate meaning) is one of the most important and misunderstood aspects of teaching pronunciation. Teachers believe that intonation is important for learners of English, but they also typically feel that intonation is very difficult to teach (Couper, 2016) although very teachable ideas have been available for over 50 years (e.g., Allen, 1971). Intonation affects the intelligibility of speech, but not in the way that other mispronunciations do. When students mispronounce vowel sounds (e.g., man pronounced like men), consonant sounds (e.g., light pronounced like night), and word stress (e.g., comBINE said as COMbine), it is possible that their mispronunciation will result in a completely different word.

The same problem does not apply to the two major aspects of intonation, final pitch movement and pitch emphasis on prominent syllables. For final intonation, using falling intonation on a yes/no question may sound more businesslike while using rising intonation may sound more polite (Thompson, 1995), but both are possible and perfectly reasonable intonations to use when asking a question. Inappropriate uses of intonation thus may be interpreted as social failings rather than linguistic ones. Gumperz (1982) reported on just such a situation in a British Air cafeteria. Women from Pakistan and India offered food to English pilots and airline staff using falling intonation, such as saying “Gravy.” The airline staff felt that the servers were being rude, and the servers thought that the English staff were ungrateful, and the makings of an interpersonal war between servers and staff was brewing, causing management to bring Gumperz in to analyze what was happening. He discovered that the falling intonation in the servers’ native languages was considered polite, but in English, politeness was indicated by the use of rising intonation, as in “Gravy?” In other words, the wrong intonation led not to misunderstanding the word but to a different kind of unintelligibility, misunderstanding the speakers’ intentions.

Placing emphasis on different words in an utterance, a second important use of intonation in English, also is sensitive to context. For example, in repeated questions such as “Where are you from,” emphasis shifts from the last word (FROM) in A’s initial question to YOU in B’s repeated question because of the changing referent for “you”, then shifts again to WHERE to express surprise at the answer.

A: Where are you FROM?

B: Iowa. Where are YOU from?

A: Easter Island.

B: Wait. WHERE are you from?

This short article, divided in two parts, is based on a presentation given as part of the SPLIS Academic session in 2019. The second part will be published in the next As We Speak and will talk about final intonation. Part 1, the focus of this article, describes useful aspects of teaching prominence (or sentence stress) that can help any teacher begin to teach it. Prominence is a critical part of intelligible speech because it

1. gives a shape to connected speech;

2. calls attention to a speakers’ use of comparisons and contrasts; and

3. expresses the relative importance of information in a spoken message.

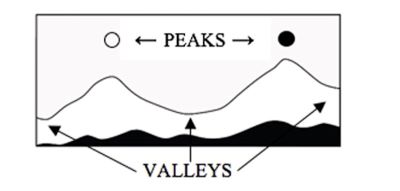

Speech shapes

English typically has a speech shape with prominent syllables early and late in the sentence. This is sometimes called the hat pattern (Bolinger, 1986). (Think of the type of hat worn by Indiana Jones, or Clark Kent when he’s not Superman.) The hat pattern can also be visualized by thinking of a suspension bridge, in which the two ends of the bridge are supported by a high point, as in Dickerson (2019). Dickerson also calls this the two-peak profile, as shown in the picture from his article in which prominent syllables are peaks and non-prominent syllables are labeled as valleys (p. 37).

Sometimes a sentence only has the late emphasis (Peak 2) on the stressed syllable of the last content word (such as a noun, verb or adjective), which is critical in shaping English speech and in the ways that listeners interpret the speaker’s message.

One way to practice this English speech shape is to use sentences from the textbook or to have students choose their own sentences from a presentation. The sentences should not be overly long since it is hard to pronounce long sentences in a single phrase. Have students identify an early and a late word to emphasize, using higher pitch on both peaks and deaccenting the rest of the words (i.e., pronouncing the words in a pitch valley). Even though this type of reading aloud is not very communicative, getting used to speaking English with this speech shape will make learners immediately more comprehensible.

The next sections describe two other uses of intonation that apply to different functions of prominence. The first is the use of prominence to express comparisons and contrasts, and the second is the use of prominence to call attention to new and given information.

Before looking at contrasts and new information, it is helpful to understand normal emphasis in English sentences to understand how prominence works to express contrasts and to express new information. Normal emphasis usually occurs on the stressed syllable of the last content word (e.g., noun, verb, adjective) in a spoken sentence. This pattern occurs about 90% of the time in spoken English (Crystal, 1969), but there are well-documented exceptions to this pattern.

Expressing comparisons / contrasts

If you were asked to describe the differences in the two pictures below (from Levis & Muller Levis, 2018), you would likely say something like “In the first picture, the cat is ON the table, but in the second, the cat is UNder the table.” In doing so, you are using contrastive emphasis to express the salient differences between the pictures.

In your description, you have placed emphasis on the two prepositions rather than the final content word “table”. This points out that contrastive prominence can occur anywhere it is important for a speaker’s message.

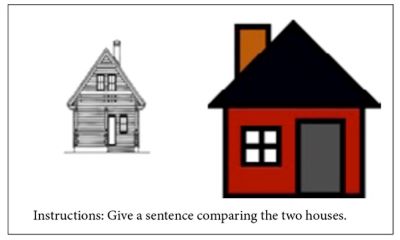

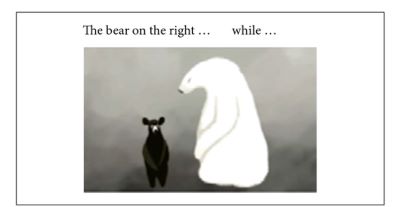

There are many ways to teach contrasts, but we have found that the use of contrasting pictures allows language learners to learn to produce contrasts without having to rely upon reading an already written out text. The picture of the two cats has only one obvious contrast, but learners can express many contrasts when they are asked to give a sentence comparing the pictures below (also from Levis & Muller Levis, 2018). We have found that up to 10 students can come up with different comparisons in using this set of pictures.

To express contrasts clearly, we also have found that it is important to help learners practice the words used to express contrasts. Phrases like “In the first picture” and contrasting conjunctions like “but” and “while” are especially helpful and can be incorporated into describing contrasts (Levis & Muller Levis, 2018, p. 150).

Marking informational importance

Although English speakers typically use intonational prominence to highlight content words at or near the end of each phrase, in discourse (extended speech), prominence is used to highlight new information being introduced by speakers, while final old information (information that was already introduced) is subsequently deaccented and pronounced with low pitch, as in the example below.

“I want to tell you about studying engiNEERing. . .(2) There are many different KINDS of engineering. . .(3) For exAMple. . . (4) I studied inDUStrial engineering”

The use of prominence for new information and deaccented low pitch for given information is common in conversation and in presentations, such as in lectures.

To teach informational prominence, it is helpful to use discourse examples to help learners understand how prominence can change, and how words that were prominent before should be deaccented when they are no longer new information. The next example is a slight adaptation of an authentic lecture on ayurveda health practices with 11 phrases (Levis, Muller Levis and Sonsaat Hegelheimer, n.d.). Note that sometimes new information is also the last content word (Phrase 1), and sometimes it is not the last context word (Phrase 2). This also shows up in Phrases 7-11, in which repeated words are both prominent and deaccented in different phrases. But placing prominence on the words as they are marked means that listeners will find the message easier to process and that they will remember more of what they heard (Hahn, 2004).

Final prominent and non-prominent words

(1) Today I’m going to talk about ayurVEda . . . (2) I’m just going to start out by deFINing ayurveda . . . (3) Ayurveda comes from two Sanskrit ROOTS . . . (4) AYur . . . (5) meaning having to do with LIFE . . . (6) and VEda . . . (7) meaning wisdom or KNOWledge . . . (8) So, systematized wisdom or knowledge is sometimes called SCIence . . . (9) sometimes it’s translated as science of LIVing . . . (10) sometimes it’s WISdom of living . . . (11) sometimes it’s knowledge of RIGHT living . . .

Conclusion

Laura Hahn (2004) showed that an international teaching assistant who used correct prominence patterns was more effective in communicating. The listeners remembered more, remembered more accurately, and thought the correct prominence patterns made the speaker more likeable. Her study showed that prominence is essential to effective communication because it helps listeners know what speakers intend beyond the meanings of the words and grammar alone.

References

Allen, V. F. (1971). Teaching intonation, from theory to practice. TESOL Quarterly, 5(1), 73-81.

Bolinger, D. L. M. (1986). Intonation and its parts: Melody in spoken English. Stanford University Press.

Couper, G. (2016). Teacher cognition of pronunciation teaching amongst English language teachers in Uruguay. Journal of Second Language Pronunciation, 2(1), 29-55.

Crystal, D. (1969). Prosodic systems and intonation in English. Cambridge Studies in Linguistics 1. Cambridge University Press.

Dickerson, W. (2019). The ripples of rhythm: Implications for ESL instruction. In J. Levis, C. Nagle, & E. Todey (Eds.), Proceedings of the 10th Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching conference, ISSN 2380-9566, Iowa State University, September 2018 (pp. 36-54). Ames, IA: Iowa State University

Gumperz, J. J. (1982). Discourse strategies (No. 1). Cambridge University Press.

Hahn, L. D. (2004). Primary stress and intelligibility: Research to motivate the teaching of suprasegmentals. TESOL Quarterly, 38(2), 201-223.

Levis, J. M., & Muller Levis, G. (2018). Teaching high-value pronunciation features: Contrastive stress for intermediate learners. CATESOL Journal, 30(1), 139-160.

Levis, Muller Levis & Sonsaat-Hegelheimer, S. (n.d.). Pronunciation for a purpose. Unpublished textbook.

John Levis is Professor of Applied Linguistics and Technology at Iowa State University. He started the Journal of Second Language Pronunciation and Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference. |