|

The English language poses a plethora of pronunciation elements that English language learners (ELLs) find very difficult to master during their language learning journey. While segmentals (vowels & consonants) and suprasegmentals and connected speech (e.g., stress, rhythm, intonation, linking) are both important for clear pronunciation, research keeps demonstrating that prosody and connected speech phenomena are key to increasing comprehensibility (Derwing et al., 1998; Gordon & Darcy, 2022). One prominent connected-speech feature is linking, or the specific ways in which sounds are connected to each other. This is an important aspect because it involves connecting words and syllables together smoothly in spoken language and facilitates adherence to the prosodic requirements of the language. Celce-Murcia et al. (2010) stressed that learners who do not understand linking will not be able to connect words together appropriately and may sound less intelligible, as words in spoken discourse run together and are not spoken in an isolated manner. The English language poses a plethora of pronunciation elements that English language learners (ELLs) find very difficult to master during their language learning journey. While segmentals (vowels & consonants) and suprasegmentals and connected speech (e.g., stress, rhythm, intonation, linking) are both important for clear pronunciation, research keeps demonstrating that prosody and connected speech phenomena are key to increasing comprehensibility (Derwing et al., 1998; Gordon & Darcy, 2022). One prominent connected-speech feature is linking, or the specific ways in which sounds are connected to each other. This is an important aspect because it involves connecting words and syllables together smoothly in spoken language and facilitates adherence to the prosodic requirements of the language. Celce-Murcia et al. (2010) stressed that learners who do not understand linking will not be able to connect words together appropriately and may sound less intelligible, as words in spoken discourse run together and are not spoken in an isolated manner.

In this article, we will provide a variety of practice and production activities that can be used to help improve linking in ELLs. In order to ensure that ELLs develop a solid understanding of this aspect, linking should be taught explicitly, as explicit and systematic instruction tends to be effective in L2 pronunciation development (Lee et al., 2015; Saito & Plonsky, 2019). Even though pronunciation is oftentimes overlooked when it comes to language instruction, connected speech aspects such as linking are disregarded even more so. Using Celce-Murcia et al.’s (2010) communicative framework of pronunciation teaching, the primary focus of these activities will be centered around linking types such as intervocalic consonant sharing, insertion of /y/ and /w/ glides, resyllabification, and lengthened articulation. It is also important to mention that ELLs should be consistently monitored to determine whether an individual or group of students need additional instruction or explanations. Since these activities are centered more towards group-oriented work, students are encouraged to interact and negotiate meaning, which will require them to expand the use of linked forms learned under controlled conditions to more spontaneous situations (Celce-Murcia et al., 2010; Ellis & Shintani, 2014).

Insertion of Glides and Intervocalic Consonant Sharing

Description and Analysis: The instructor will present the class with insertion of glides and intervocalic consonant sharing. During this first part of the lesson, a definition along with a handful of examples will be presented to the classroom, and examples should be modeled by the teacher for learners to notice how glides help link sounds to each other. The students will then use this information to complete the tasks later in class.

Listening Discrimination: After the explicit presentation, the students will listen to an audio and follow along with a transcript. From here, the students will distinguish where the elements of glide insertion and intervocalic consonant sharing are being used. This is an individual activity that can be checked with the whole class so that the students share their answers together to see if they are target-like. This transcript and audio will be used throughout multiple lessons.

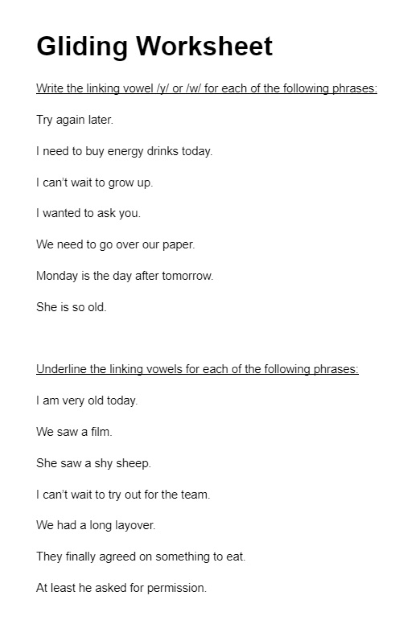

Controlled and Guided Practice: Once the listening discrimination activity is over, the students will be given a worksheet that gives them a visual representation of where the glides could potentially be inserted into words or phrases as well as the rules that follow. It is important that the instructor informs the students that these glides only occur when linking vowel to vowel. Be sure to include examples of this.

Figure 1. Gliding Worksheet

Individually, the students will draw linking arrows between sounds to raise awareness of where linking in glides and consonant sharing occurs. After doing so, students will pair up with a partner and practice reading to each other to check if they have linked the sounds. During this activity, the teacher will monitor and observe if the student pairs have identified the glides and consonant sharing and if pronunciation is target-like or not.

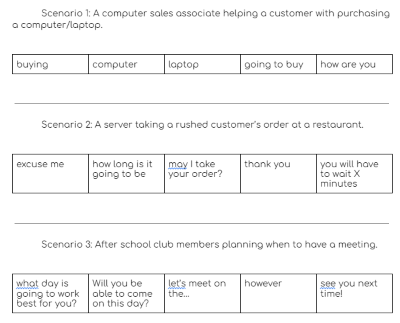

Communicative Practice: The students will be given a number of scenarios, and inside of each scenario, they will be given a word bank that corresponds to the scenario they choose. Each word or phrase will contain insertion glides and intervocalic consonant sharing examples. The students will write a script for their selected scenario and practice it before acting it out in front of the class. It is important to encourage the students to use the script only as a guide, but not to read out loud from it. The purpose of the activity is to speak as naturally as possible using connected speech. Students must use as many words in their word bank as possible in order to practice producing glides and consonant sharing.

Resyllabification & Lengthened Articulation

Description and Analysis: The students will refer back to the transcript from the lesson described before and partner up to take turns reading the transcript before listening to an audio. After the students have finished, the instructor will ask if the pronunciation was easy or difficult. Then, to raise awareness in learners of other linking features, the students will listen to a recording of a speaker uttering the sentences that do not contain lengthened articulation or resyllabification. The teacher will then ask for confirmation if this is how the students pronounced the sentences and if they sound natural or not. Next, the teacher will play the same audio recording which also contains the target-like uses of lengthened articulation and resyllabification. Afterwards, the teacher will go on to explain exactly what lengthened articulation is, and will emphasize that this phenomenon frequently occurs as a result of a consonant clustering caused by plural or past tense endings being added to a verb. Finally, the teacher will read out loud some examples of this type of linking in phrases modeling proper pronunciation for the students. The students will listen and repeat after the teacher.

Figure 2. Scenarios

Listening Discrimination: Now, the students will listen to the same audio from the first lesson and follow along with the transcript. From here, the students will distinguish where the elements of resyllabification and lengthened articulation are being used and circle them in the transcript. Afterwards, the whole class will share their answers.

Controlled Practice: The students will be given a worksheet that contains a fill-in-the blank exercise. The activity goes as follows: There will be a word presented to the student with three word options that follow, and the students’ task is to decide which word combination will create lengthened articulation and resyllabification. After identifying the correct combinations, the students will practice in pairs reading the phrases to each other paying attention to lengthened articulation and resyllabification. It is important to mention that this series of activities can be completed twice, one time as lengthened articulation and then again as resyllabification.

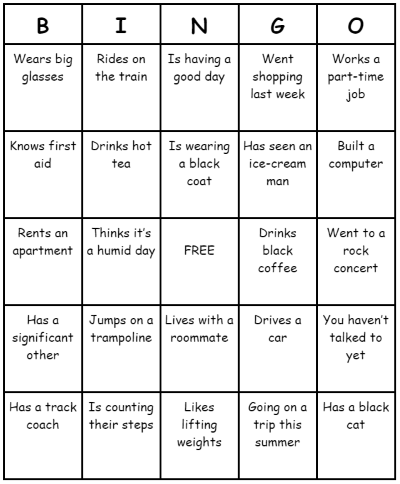

Guided Practice: Students will be handed a bingo sheet activity. The bingo sheet contains a 5x5 table with statements in each square. These statements contain instances of lengthened articulation. The statements are broad and may apply to some students in class. For example, I wear big glasses; I’ve seen a pink car; I have good time management; I’ve received a reader reward, etc. Students will go around the room verbally asking their classmates if any of the statements apply to them. If the statement applies to the student being questioned, that student may sign their name on the other student’s bingo sheet. Students must do this until they have five squares with signatures in a row - a bingo.

Communicative Activity: Students will be paired up in twos. They will be asked to roleplay that one is sitting down to order food at a restaurant, while the other is their server taking the order. The students will be given a list of restaurant names that they will be ordering food from as well as a list of possible items from a menu. Each restaurant name and food item will have either resyllabification or lengthened articulation that the students will need to produce.

Figure 3. BINGO

Conclusion

The communicative framework of pronunciation teaching by Celce-Murcia et al. (2010) is primarily used in these lessons to introduce linguistic forms to the students, to guide them through controlled practice, and to help them transfer this to more communicative contexts. However, these lessons can be adapted to lower-proficiency students by using simpler vocabulary, more images and videos for presentation portions, and having students make shorter and simpler sentences for assessments. Some adaptations for higher proficiency students could include more advanced vocabulary or students creating monologues.We would like to encourage instructors to create their own materials and adapt them to the levels and interests of their own students. Creating voice recordings of the example scripts with different speakers such as the instructor, colleagues, and even other students could expose learners to different accents, which is important to develop perceptual skills for further pronunciation development (see Thomson, 2022). In other words, this practice will give students the opportunity to hear the script(s) being spoken by different speakers in a variety of ways. We hope other teachers find our recommendations suitable for adaptations in other teaching contexts to implement pronunciation teaching systematically.

Refer to this link for the materials mentioned in all of the lessons.

References

Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D., & Goodwin, J. M. & Griner, B. (2010). Teaching pronunciation: A course book and reference guide (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Derwing, T. M., Munro, M. J., & Wiebe, G. (1998). Evidence in favor of a broad framework for pronunciation instruction. Language Learning, 48(3), 393-410.

Ellis, R. & Shintani, N. (2014). Exploring language pedagogy through second language acquisition research. Routledge.

Gordon, J. & Darcy, I. (2022). Teaching segmentals and suprasegmentals: Effects of explicit pronunciation instruction on comprehensibility, fluency, and accentedness. Journal of Second Language Pronunciation, 8(2), 168-195.

Lee, J., Jang, J., & Plonsky, L. (2015). The effectiveness of second language pronunciation instruction: A meta-analysis. Applied Linguistics, 36(3), 345-366.

Saito, K. & Plonsky, L. (2019). Effects of second language pronunciation teaching revisited: A proposed measurement framework and meta-analysis. Language Learning, 69(3), 652-708.

Thomson, R. I. (2022). Perception in pronunciation training. In J. M. Levis, T. M. Derwing, & S. Sonsaat-Hegelheimer (Eds.), Second language pronunciation: Bridging the gap between research and teaching (pp. 42-60). Wiley.

William D. Kirchmann and Leland Rieks are undergraduate students pursuing their B.A. in TESOL-Teaching at the University of Northern Iowa. |