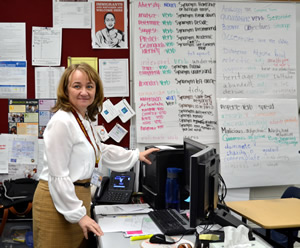

Meet Tünde Csepelyi: 2019 TESOL Teacher of the Year

Interviewed by Brooke Leach Grable

Born and raised in Hungary, Tünde Csepelyi, winner of the 2019 TESOL Teacher of the Year Award, is a nonnative-English-speaking English language teacher who formerly coordinated the same program she started at as an English language student. Now, she teaches high schoolers. She holds an MA in TESL, an MEd in educational psychology, and a PhD in language, literacy, and culture.

For nearly two decades, she has been an English language educator in various settings. Her never-ending passion toward English language teaching originates from her own English language learning experience.

Brooke Leach Grable asks Dr. Csepelyi a few questions about her personal and professional journey.

As a nonnative speaker of English, what obstacles did you face when becoming a teacher?

Upon arrival to the US, I did not speak English at all. I quickly realized that without English, I would not be able to work as a professional, let alone as a teacher. Therefore, I studied day and night—literally, as I babysat at night, I studied—and 6 years after my immigration, I was ready to be in front of a class. I will never forget my first job interview. I barely opened my mouth and introduced myself before the interviewer stopped me. He said that my accent was too heavy, and that I should take accent reduction classes before teaching in the US.

I was devastated. I had thought that if I put all my energy into my studies, I would be able to fulfill my American dream: becoming a professional, a teacher, in my new country. I cried for a day, and then called several speech therapists who all said that my accent was fine and they could not do anything with me. Then I grabbed the phonebook and called every single family center in Reno and asked them if they needed an English teacher. The fourth callee said yes! I was beyond excited.

I was devastated. I had thought that if I put all my energy into my studies, I would be able to fulfill my American dream: becoming a professional, a teacher, in my new country. I cried for a day, and then called several speech therapists who all said that my accent was fine and they could not do anything with me. Then I grabbed the phonebook and called every single family center in Reno and asked them if they needed an English teacher. The fourth callee said yes! I was beyond excited.

On March 21, 2001, I finally stood in front of students. Since then, I am aware of my nonnative status, and I made sure when I interviewed for my current position that I immediately tackled the elephant in the room: my accent. My principal, Kevin Carroll, and the department leader, Melanie Reeves, didn’t even understand what I was addressing: They saw me and not my accent. However, in the classroom, my accent is clearly an advantage. From my high schoolers to my graduate students, my accent is a trademark for authenticity when I tell my students that learning English is hard, but not impossible.

You began your teaching career as a geography and history teacher in Hungary. How is teaching subject matter the same or different from teaching English to nonnative speakers?

I was a very different person at the age of 23 when I started teaching high schoolers in Hungary. For a start, my students and I spoke the common language and culture: Hungarian. I had not experienced immigration. I had no insight into how not speaking the language changes one’s life. It was not only a matter of having or not having the career I always wanted; rather, it was more like, “I have no idea how to explain that I am sick because I don’t have the vocabulary to explain what is wrong me.” I never addressed these issues with my high schoolers. Now, whatever I teach, my mind always adds, “Would my students be able to use this piece of new knowledge in their life?” So yes, there are vast differences between teaching a subject to native speakers in the native environment and teaching English to nonnative speakers in a nonnative environment.

The experience I have gained over the years as an immigrant inspires me as a teacher to build relationships with students and their parents. I feel that what I do is not even teaching: I want my students—adults or children—to find their inner peace in their new country through my support, coaching, and okay, teaching. Whatever I bring to the classroom serves this purpose: to help my students achieve a full life in the US where they speak the language and are educated, so they have access to their dream careers. I want them to have choices.

The experience I have gained over the years as an immigrant inspires me as a teacher to build relationships with students and their parents. I feel that what I do is not even teaching: I want my students—adults or children—to find their inner peace in their new country through my support, coaching, and okay, teaching. Whatever I bring to the classroom serves this purpose: to help my students achieve a full life in the US where they speak the language and are educated, so they have access to their dream careers. I want them to have choices.

My immigrant life completely changed when I was finally able to teach. However, one fundamental idea never changed from the very beginning of my teaching career to today: I felt the same enormous responsibility for my students in Hungary as for my students in the US. We teachers can be gatekeepers and I never wanted to be one. Also, somewhere I read that students have many grumpy adults in their lives, so teachers should not be one of them. I have definitely lived by this philosophy from the moment I started teaching.

You have been involved in the “Nonnative” English Speakers in TESOL (NNEST) Interest Section as well as with CATESOL, your local organization. How do you feel those organizations helped your teaching?

My first TESOL [conference] took place in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 2002. My nonnative-English-speaking professor—Elza Major—invited me to that conference, where I presented twice: first at the graduate student forum and then at the main conference with other grad students and two professors. You can imagine how excited I was! I also remember that I met authors from my textbooks: Eli Hinkel, Neil Anderson, Tove Skutnabb-Kangas, and many others. They were real people after all and they were willing to talk to me, a grad student. I attended as many workshops as I could, taking away many, many teaching tips and research ideas.

From that point on, I made sure I saved up for the yearly TESOL conference and I am proud to say that I have not missed a TESOL conference since I have begun attending. At the beginning, I wanted teaching tips, but as my career has changed, my TESOL interests changed accordingly. When I became an administrator, my focus at TESOL shifted from teaching tips to administrative issues. As I moved from ABE EL to higher education and now to high school, so did my interest in the TESOL workshops. Currently, I am broadening my knowledge in special education and English language, so I can’t wait to attend workshops with these topics at this year’s TESOL. I also tend to recruit colleagues to TESOL. Even those who have been in the field for many years can learn something new there. For me, to be with like-minded people for a week is well worth it.

You have an upcoming convention session, “Am I Teaching Well?” Can you give us a preview? How did you arrive at that topic?

The enormous responsibility that I feel for my students has dominated my teaching since the very beginning. Who am I to have the privilege of teaching others? At my first TESOL in Salt Lake City, I picked up a book by Nicolic and Cabaj (2000), titled, Am I Teaching Well?, which helped me answer many of my questions. My presentation will include self-evaluation tips from this book.

Also, I strongly believe—and research also supports (e.g., Wentzel & Miele, 2016)—that across age groups, the most important factor in students’ school experience is their relationship with teachers. Relationships are especially important for the most vulnerable English learners, such as students in transition, refugees, or newcomers. My presentation will include some ideas on connecting with one’s students.

The final part of my presentation is about advocacy. I am very thankful for Diane Staehr Fenner’s work in this area. Her expertise guides me to represent the needs of my students beyond the classroom. If it were up to me, I would scream to the world that my English language students are capable of doing the work when given the chance: We must differentiate in the classroom, provide them with support during testing, and hold them to high expectations. If you feel like screaming but have recognized that that is not the right way to advocate for your students, buy Diane’s book (Advocating for English Learners: A Guide for Educators) and come to her presentation and mine.

What advice would you give other TESOL professionals who are just beginning their careers?

In one of my first English language classes, I had a wonderful student who had never taken an English class before. Her English progression greatly depended on my class preparation. She was progressing well when one day she came to tell me that she had found a job as a busgirl, so she was leaving the class.

I didn’t want her to go. If she could stay a little longer, I begged, she could be a professional just like back in Mexico. She started crying and with her broken English explained that she did not have a choice: She needed to make money to feed her children. I felt ashamed. I had never faced that dilemma before. I was not sure how to fix it.

However, she taught me a great lesson: My responsibility as a teacher is to serve students to the best of my ability and to show them doors, but the final choice—what they want to do with the knowledge that they have gained from me or which door they want to open—must be theirs. It sounds like common sense now, but that experience yielded me the ultimate epiphany: I serve my students best if I recognize their individual needs and I show utmost respect to their choices.

References

Nikolic, V., & Cabaj, H. (1999). Am I teaching well?: Self-evaluation strategies for effective teachers. Ontario, Canada: Pippin.

Wentzel K. R., & Miele, D. B. (Eds). (2016). Handbook of motivation at school. New York, NY: Routledge.

Brooke Leach Grable earned her BS in early childhood education and MA in elementary education from The University of Akron in Ohio. She holds reading and TESOL endorsements. She is the incoming chair of the Awards Professional Council for TESOL International Association. Brooke has taught children learning English in different situations, including in an international school in Shanghai; an urban Cleveland, Ohio school district; and a suburban Cleveland district. Currently, she lives in Prizren, Kosovo, as an English Language Fellow for the U.S. Department of State.