3 Strategies to Accelerate Language Acquisition in Beginning ELs

by Carmen Shahadi Rowe

Imagine you are in a foreign country learning not only a new

language, but also content. Your classroom teacher has the following learning

goal posted on the board:

Imagine you are in a foreign country learning not only a new

language, but also content. Your classroom teacher has the following learning

goal posted on the board:

Ich

werde…beschreibe die Hauptfiguren mit Beweisen aus dem Text.

If only you

had some idea what it all meant. Though you recognize some of the letters and

possibly a cognate, the sum total of the message is incomprehensible. Now,

let’s imagine for the sake of this article that the country is the United

States and the language is English.

I

will…describe the main characters with evidence from the text.

The task of moving English learners (ELs) to

proficiency in both English language development and academic standards

achievement is monumental, but attainable when supported with both

appropriately scaffolded content lessons and language instruction based on

practical English as a second language theory and methodology. Consider our

learning goal in terms of content and grammatical forms and functions. The conscientious

classroom teacher will be sure that their students are familiarized with the

academic language necessary to access the content standards, in this case a

lesson in English language arts. Vocabulary such as describe, main characters,

and evidence from the text can be made comprehensible through visuals and

anchor charts (see Figure 1).

I

will…describe the main characters with evidence from the text.

Figure 1. Main

characters anchor chart.

However,

knowledge of academic content vocabulary alone is not enough to close the

achievement gap. Students need explicit and systematic instruction in the

grammatical forms and functions of language to express their thoughts and ideas

both in speech and writing. Saunders et al. (2013) advised that English

language development instruction should include not only vocabulary, but also

syntax, morphology, functions, and conventions. Consider, again, our learning

goal, but this time through the lens of grammatical forms and functions:

I

will…describe the main characters with evidence from the text.

In this

sentence, we identify the future tense, articles, and prepositions. Though

native English speakers may have picked up these aspects of language from

countless exposures from birth on, our beginning ELs will need explicit

instruction with these grammatical forms, many of which serve as “connective

tissue” holding sentences, laden with academic vocabulary, together. When ELs

are not afforded instruction with these seemingly simple grammatical forms,

they later struggle when confronted with expanded and complex sentences. This

article includes three strategies that, when used on a routine basis, can

accelerate language acquisition among Beginning ELs.

Strategy #1:

Focus on the Sentence Using Grammatical Forms and Functions

Though

helping students at the beginning levels of English language acquisition build

their academic content vocabularies is important, it is vital that we build

them in tandem with sentence-level formation strategies. The simple sentence,

subject-verb and subject-verb-predicate, is the basic building block for

communication and paves the way for the development of compound and complex

sentences further down the road. This requires that we teach our ELs the

vocabulary of grammatical forms. Ramirez-Suarez and Shahadi-Rowe (2019) stated,

As students

are equipped with the specific vocabulary associated with the unique purposes

for writing, they can grow as autonomous writers who are able to use precise

language to express their thoughts in more sophisticated ways that will meet

college and career demands. (p. 33)

When we

equip our ELs with the know-how of forming simple sentences, we help them take

the first step toward college and career readiness. This equipping includes

explicit instruction with the basic forms and functions of language, such as

those on the ELD Matrix of Grammatical Forms (Dutro et al., 2007). A knowledge

of basic grammar will allow students to move beyond word-level communication to

sentence-level communication, an often neglected aspect of language

instruction. ELs and native English speakers alike receive lots of support with

learning vocabulary at the word level. An understanding of academic vocabulary,

such as describe, characters, and evidence, is useful; however, without a

knowledge of basic grammatical forms and how they work, beginner ELs will be

ill-equipped to string words together to form coherent sentences that will

ultimately enable them to succeed when tasked with writing assignments, such as

paragraphs and essays, at the discourse level. Our job as teachers is to give

beginner ELs knowledge of sentence-level constructs.

We can help

our beginner ELs build academic discourse, one sentence at a time, by insisting

that they routinely answer questions and express their thoughts in complete

sentences. Remember, native English speakers had the luxury of hearing

vocabulary embedded in sentences countless times before producing them in their

speaking. By providing activities that include repetition, we can help solidify

the acquisition of subject pronouns, verbs, and other grammatical forms. For

example, when teaching students basic classroom vocabulary, include

communicative activities that require students to use the vocabulary in

complete sentences, preferably asking and answering questions to simulate

authentic conversations. One of my favorite activities is Twenty Questions (Appendix A), which requires the use of what I have dubbed as the High-Utility Verbs (Appendix B), such as to want. When teachers use a progression of

grammatical forms, it helps lower the chances that gaps will exist in their

ELs’ language acquisition.

We can help

our beginner ELs build academic discourse, one sentence at a time, by insisting

that they routinely answer questions and express their thoughts in complete

sentences. Remember, native English speakers had the luxury of hearing

vocabulary embedded in sentences countless times before producing them in their

speaking. By providing activities that include repetition, we can help solidify

the acquisition of subject pronouns, verbs, and other grammatical forms. For

example, when teaching students basic classroom vocabulary, include

communicative activities that require students to use the vocabulary in

complete sentences, preferably asking and answering questions to simulate

authentic conversations. One of my favorite activities is Twenty Questions (Appendix A), which requires the use of what I have dubbed as the High-Utility Verbs (Appendix B), such as to want. When teachers use a progression of

grammatical forms, it helps lower the chances that gaps will exist in their

ELs’ language acquisition.

Strategy #2:

Teach Vocabulary Within the Context of Grammatical Lexicons

We can help

accelerate our students’ learning of English by organizing grammatical forms

into meaningful lexicons, or groups of related words. We know that ELs rarely

acquire new language after one exposure. By organizing the grammatical forms in

meaningful ways, we not only help students retain the information, but we also

help them to retrieve it once our lesson is over.

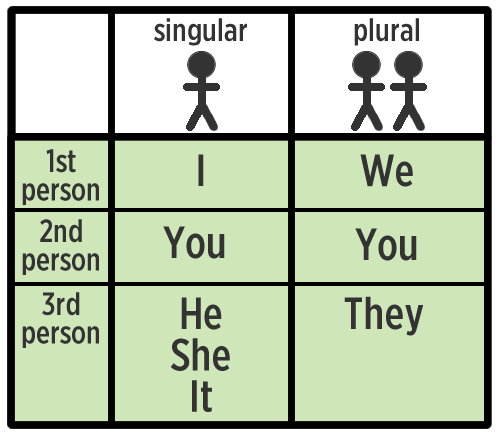

We have all

been there. We teach a mini–grammar lesson on subject pronouns, complete with

total physical response and activities to provide multiple repetitions for

students developing their receptive and productive language, all at the

sentence level. However, we teachers become discouraged when 1 week later our

students fail to use the correct subject pronouns in their speaking or writing.

Research and experience tell us that students need many repetitions with new

content before mastery occurs. So, how will we provide a way for our students

to access the grammatical forms and their uses in the future when our

mini-lesson is a distant memory?

Lexicon: Subject

Pronouns

Figure 2. Lexicon

anchor chart.

Making

lexicons available to students for future reference, in the form of an anchor

chart (see Figure 2) or an entry in a student notebook, can provide our ELs

with a valuable tool when attempting to produce language, especially at the

sentence level.

An analysis

of sight words and basic vocabulary that all students are expected to know with

automaticity at the elementary level reveals that the majority of these words

include common verbs and other basic grammatical forms, such as nouns,

adjectives, pronouns, prepositions, and conjunctions. Now, consider the

organization of these sight words in most elementary classroom word walls.

Typically, the words are alphabetized, but rare is the learner who stores or

retrieves sight words by the first letter of a word.

One useful

tool for helping beginner ELs access lexicons of grammatical forms and their

functions is the Writer's Placemat for Beginner ELs (Appendix C). This writer’s

tool explicitly organizes the grammatical forms into lexicons by their

functions. Our brains look for meaningful patterns when storing and retrieving

information, a fact that makes arranging vocabulary into lexicons by their

functions a powerful teaching strategy.

Strategy #3:

Use Timelines to Teach Grammatical Forms and Functions

The use of

timelines is often confined to social studies classrooms. They are a staple

when teaching history to help students understand the chronology and context of

events, as well as continuity, or the duration of an event. Though the most

innovative teacher may include the use of timelines in the language arts

classroom as a story is read to recount the order in which events occurred,

their use can also be a powerful tool when teaching grammatical forms and their

functions:

- Tenses:

Use timelines from the beginning to teach tenses. Introduce the timeline along

with signal words that indicate which tense should be used (see Figure 3).

Start with the most basic signal words, such as yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

Include these words as part of a daily routine: “Today is Tuesday, May 2, 2020.Yesterday was Monday, May 1, 2020. Tomorrow will be Wednesday, May 3, 2020.” As

students become familiar with these signal words, begin to add to the lexicon

of phrases, such as last week, right now, and next year.

Figure 3. Example

timeline to teach tenses.

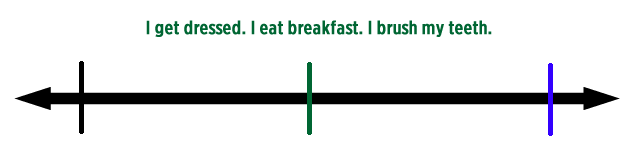

- Prepositions of Time: Once beginner ELs are familiar with the concept of

timelines, you can use them as a context in which to teach prepositions of

time, such as before and after to indicate the chronology of events. The

following timeline example (Figure 4) shows chronology within the present tense

and can help students better grasp the meaning of prepositions: “I get dressed before I eat breakfast. I brush my teeth after I eat breakfast.”

Figure 4. Example

timeline to teach prepositions of time.

Figure 4 lays the

bedrock for the subsequent teaching of chronology in the past tense, “I got

dressed before I ate breakfast,” and in the future tense as well, “I will get

dressed before I eat breakfast.” Pictures of the actions may be added to the

timeline to provide additional comprehensible input for students.

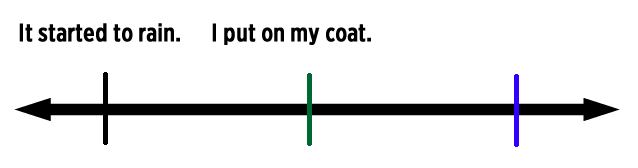

- Cause and

Effect: Students’ understanding of cause and effect is bolstered through the

use of timelines. If the concept of time has been reinforced routinely in a

classroom, beginner ELs will quickly understand that with cause and effect

relationships, one event precipitates another. Timelines become a vital tool in

crafting cause and effect sentences with appropriate syntax modeled by the

teacher. In the example, “It started to rain, so I put on my coat,” students

are able to comprehend, with the aid of a timeline, the cause and effect

relationship (see Figure 5). Additionally, offering students more than one way

to produce cause and effect statements, with teacher modeling of syntax,

accelerates language. For example: “I put on my coat because it started to

rain.” As soon as students have mastered the conjunction so and because,

encouraging them to use other vocabulary from the cause and effect lexicon,

such as therefore and as a result, will bolster their vocabularies.

Figure 5. Example

timeline to teach cause and effect.

Concluding

Thoughts

Though

simultaneously learning English and content standards can be challenging, we

can accelerate our ELs’ journey along the path of English language acquisition

through routine strategies. Informing instruction through the use of a

progression of language forms to help students build coherent sentences is the

first step. In addition, organizing grammatical forms into lexicons based on

their functions helps students not only better understand the forms, but also

helps with retrieval. Finally, using timelines to teach tenses, prepositions,

and conjunctions is an effective tool for providing comprehensible input.

References

Dutro, S.,

Prestridge, K., & Herrick, J. (2007). ELD matrix of grammatical forms.

E. L. Achieve. http://www.elachieve.org/images/ela/symposium/1s3_seceld

_distillinglanguage_post/seceld_tab211_13_matrix_tan_062209.pdf

Ramirez-Suarez, W. J., &

Shahadi Rowe, C. (2019). Challenging English learners to improve academic

discourse. The Pennsylvania Administrator (Winter).

Saunders, W., Goldenberg, C.,

& Marcelletti, D. (2013). English language development: Guidelines for

instruction. American Educator, 37(2), 13–39..

Dr. Carmen Shahadi

Rowe earned her master’s in TESOL from Eastern Mennonite University and her

doctorate in educational leadership from Immaculata University. She has 20

years of experience in public education teaching Spanish and ESL, K–12. She

serves as an ESL instructional coach in the School District of Lancaster in

Pennsylvania, teaches courses in higher education for teachers in training, and

frequently presents trainings on topics related to education.