Practical Applications: Multimodal Projects for Adult MLEs

by Rachael Krummel and Devin McCain

Today’s society rewards self-driven job seekers

with technological aptitude, critical and creative thinking skills, and the

tenacity to apply what they learn. Do adult intensive English programs meet the

demands of the workforce by providing more than the usual English curriculum?

Selfe and Selfe’s 2008 study suggests that the assignments given to today’s

students are almost identical to the assignments of their parents and

grandparents, and most adult intensive English programs do not offer courses on

digital literacy or multimodal composition. If education is to be the great

equalizer, perhaps it is time to turbo-charge that curriculum with digital

multimodal literacy skills, so our students can be efficient consumers and

literate producers of multimodal texts.

Today’s society rewards self-driven job seekers

with technological aptitude, critical and creative thinking skills, and the

tenacity to apply what they learn. Do adult intensive English programs meet the

demands of the workforce by providing more than the usual English curriculum?

Selfe and Selfe’s 2008 study suggests that the assignments given to today’s

students are almost identical to the assignments of their parents and

grandparents, and most adult intensive English programs do not offer courses on

digital literacy or multimodal composition. If education is to be the great

equalizer, perhaps it is time to turbo-charge that curriculum with digital

multimodal literacy skills, so our students can be efficient consumers and

literate producers of multimodal texts.

The reality is that students are already learning

through multiple avenues of communication: YouTube and TikTok videos, Spotify

podcasts, infographics, websites, and others. “Literacies are not static”

(Selfe & Selfe, 2008). Literacy has gone digital, with multiple modes

of communication, just like many aspects of life, and so should literacy

education.

What Is Digital Multimodal Composition?

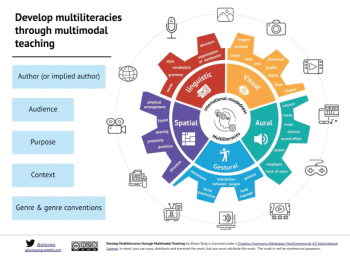

Communication itself consists of more than just

written or spoken language (see Figure 1). Digital multimodal composition (DMC)

involves communicative literacy in all five modes. DMC projects immerse

multilingual learners of English (MLEs) in the current, sociocultural writing

norms of different genres and communicative modes through research based on

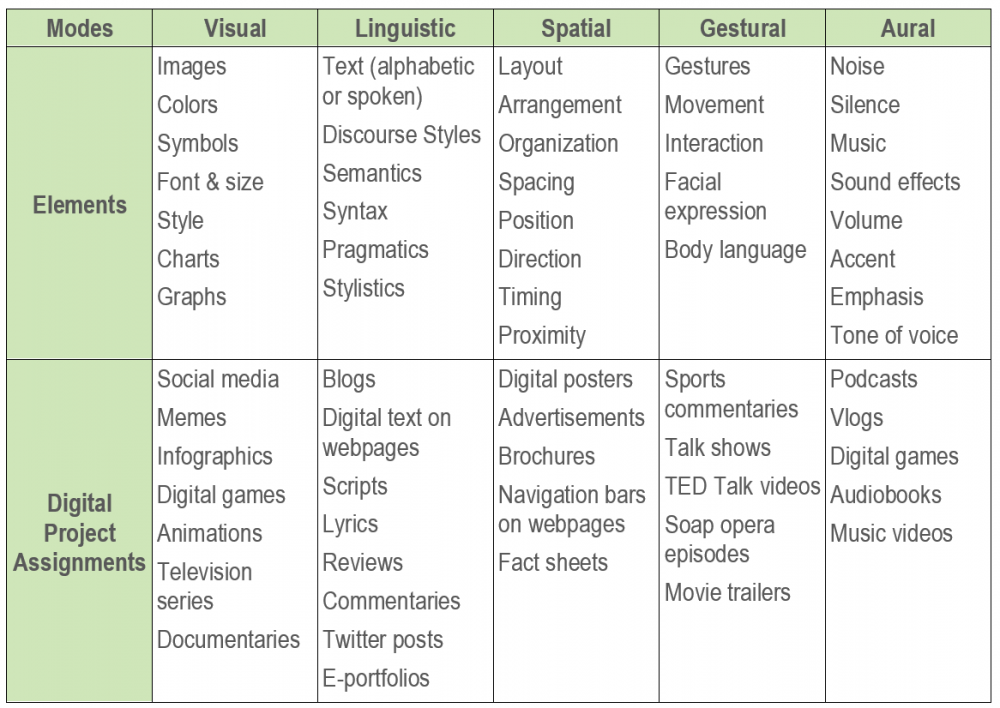

students’ interests and preferences. Table 1 illustrates some examples of

digital project assignments.

Figure 1. Modes of communication. (Source: Alison

Yang; Creative

Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License; click here to enlarge)

Table 1. Digital Multimodal Composition

(Click here to enlarge)

Though multimodal texts do not necessarily require

digital tools, there is a strong incentive for MLEs to be proficient in DMC.

When creating a podcast or similar text that emphasizes the aural mode,

students must consider their audience, purpose, and context, and organize ideas

for content coherently, just as their colleagues do in traditional writing

classes. Some educators, students, and parents argue that teaching language

skills using a project-based DMC may not be “academic,” but we see this methodology

as relevant because multimodal communication is commonplace in real life.

In addition, students develop soft skills when

working on a constructivist, project-based multimodal and digital assignment

that are highly sought after by employers, such as

- communication,

-

critical thinking and

problem-solving,

-

collaboration,

-

self-directed initiative,

-

metacognition,

-

ownership and accountability,

-

ethical responsibility,

-

creativity,

and

-

punctuality.

Why Digital Multimodal Composition With Project-Based

Learning?

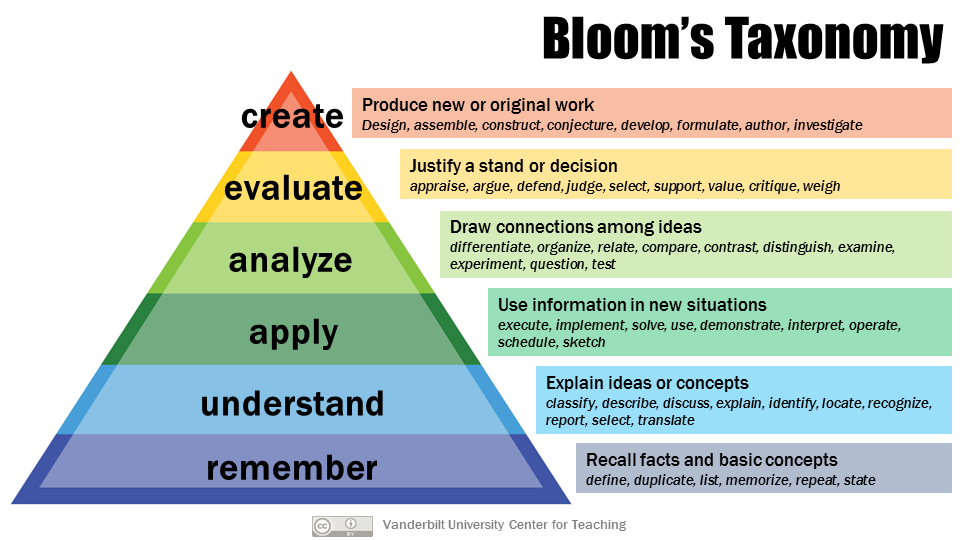

Project-based learning (PBL) is almost synonymous

with self-directed learning, which in turn results in a deeper and more

relevant kind of learning, or the higher levels in Bloom’s Taxonomy: apply,

analyze, evaluate, and create (see Figure 2). The engaging aspects of a DMC

project not only excite learners, but also motivate and help them build a

plethora of relevant and highly coveted soft skills. The traditional

teacher-centered classroom emphasizes rote memorization and doesn’t provide the

same affordance an engaging project-based curriculum does, or personalized

project learning experience that focuses on student choice and voice. PBL gives

more agency to develop self-efficacy and critical viewing competencies as

students consider options, brainstorm ideas and solutions, iterate their

projects, and defend their choices. All these activities engage higher order

thinking skills and expose learners to transferrable 21st-century career

readiness skills, thus helping them to excel in a world where digitally driven

communication is fast replacing the pen and paper mode of

communication.

Figure 2. Bloom’s Taxonomy. (Source: Vanderbilt

University Center for Teaching; Creative

Commons Attribution license; click here to enlarge)

The Backstory

After conducting rigorous research to establish the

benefits of project-based DMC and forming a committee with two other

colleagues, our next step was to find one or more courses into which we could

incorporate it. Because there were few multimodal, project-based curricula for

adult MLEs we could use to avoid reinventing the wheel, we pored through more

research-based, open educational resources and tried and tested curricula from

public schools and English as a foreign language programs. We also decided that

a four-course series called Practical Language Applications (PLA) would most

readily lend itself to adaptation. These 20-hour courses, which meet in

computer labs on Fridays, were initially geared toward Continuing Education

Intensive English F1 students with English proficiency levels A1 to B2,

according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFRL),

as shown in Table 2.

Finally, we devised thoughtful student language

objectives and implemented both formative and summative assessments—the former

with a student proposal and action plan form, the latter with a rubric and

final reflection essay. With our regular intensive English courses anchoring

the necessary instruction of English language skills and strategies Monday to Thursday,

the PLA curriculum supports English language application and digital

literacy.

The Curriculum

Each MLE authors an original and relevant

multimodal project that consists of a combination of motion, images, text, and/or

audio (see Table 2 and Figure 3). Students have autonomy when selecting their

topics and choosing whether to work alone or in a group. According to a recent

review of student surveys, they consider this the best part of the

process.

Table 2. Practical Language Application

Courses

|

PLA

Courses |

Language Focus |

CEFRL

Scale |

Digital Multimodal

Project |

|

PLA 1 |

Listening

& Speaking |

A1 |

PowerPoint

presentation (with embedded images, voice-over audio or video

clips) |

|

PLA 2 |

Reading &

Writing |

A2 |

Blog |

|

PLA 3 |

Listening

& Speaking |

B1 |

Podcast

(scripted) |

|

PLA 4 |

Reading &

Writing |

B2 |

E-portfolio |

CEFRL = Common

European Framework of Reference for Languages; PLA = Practical Language

Application

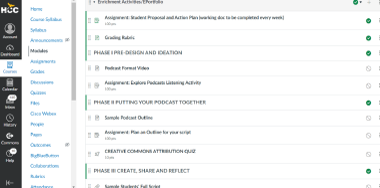

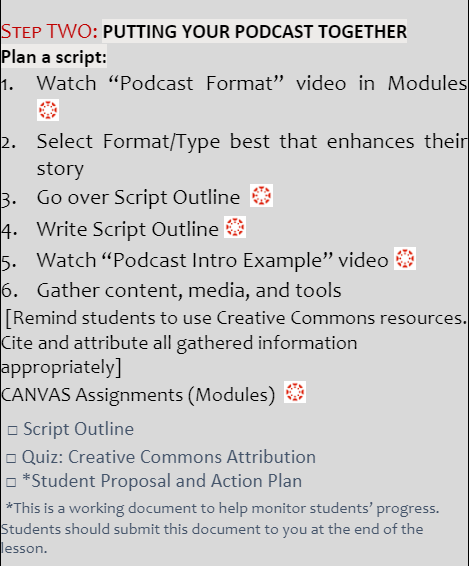

MLEs are guided through every phase of the process

and are expected to monitor their progress by completing a student proposal and

action plan form and other assignment sheets in the learners’

Canvas LMS (see Figure 4). Some parts of the course follow the flipped teaching

methodology as the instructor selects short video clips provided in each module

for students to view before class. During class, learners work on their

projects using the action plan form as a pacing tool. Learners also complete

assignments designed to scaffold the project’s creation in each module of

Canvas LMS. These activities are assigned to reinforce English language skills

and can serve as a self-study where they can be extended as homework. The

projects themselves are completed in five phases:

- Phase I: Ideation

- Phase II: Development

- Phase III: Share (peer review)

- Phase IV: Publication (complete

project)

- Phase V: Reflection

The instructor’s role is to provide lessons on

basic digital literacy, multimodal composition, and language skills through

individual and/or group discussions. Before accepting a PLA course, instructors

are given clear, standardized pacing guides (see Figure 5) that mirror the

modules in the learners’ Canvas LMS and trained in aspects of digital modes of

communication. In addition, instructors are provided with open educational

resources to help them familiarize themselves with the aspects of DMC. One such

resource is a peer-reviewed open textbook series called Writing

Spaces: Readings on Writing; this is a treasure trove of

free educational resources available under a Creative Commons

license.

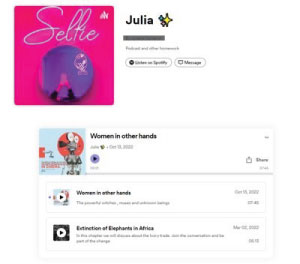

Figure 3. A student’s podcast.

Figure 4. Canvas LMS practical language application

modules and assignment sheets.

Figure 5. Excerpt from the instructor pacing guide.

Conclusion

Literacy education doesn’t have to be static. PLA

gives learners voice and choice on the projects they desire. The bonus to such

instructional mentality is the relevance of it all: students gain genre

awareness without feeling a sense of alienation from a static or monotonous

curriculum, and “explore the context in which the texts are produced as well as

reasons for the linguistic choices that students are making” (Partridge et al,

2009, p. 77). As John Dewey stated in 1897, “Education is not preparation for

life; education is life itself.” We hope that the ideas espoused in this

article help other instructors of MLEs plan lessons and design curricula that

will hold up in today’s increasingly digitalized world.

References

Dewey, J. (1897). My pedagogic creed. School Journal, 54(3),

77–80.

Partridge, B., Harbon, L., Hirsch, D., Shen, H.,

Stevenson, M., Phakiti, A., & Woodrow, L. (2009). Teaching

academic writing: An introduction for teachers of second language

writers. University of Michigan Press.

Selfe,

R. J., & Selfe, C. L. (2008). “Convince me!” Valuing multimodal

literacies and composing public service announcements. Theory Into

Practice, 47(2), 83–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40071528

Rachael

Krummel holds a Master of Education in

TESOL from Sam Houston State University. As a lead faculty at Houston Community

College CE Intensive English program, she brings over two decades of invaluable

experience in teaching English language in Asia and the United States. Rachael

is committed to empowering her students with the language skills and confidence

to navigate our evolving world. Outside her professional life, she enjoys

meaningful moments with her family and pets.

Devin

McCain is one of the CE Intensive English

lead faculty at Houston Community College. He previously tutored college and

university students, taught at an English immersion camp in South Korea, and

worked as an ESL and GED instructor at McLennan Community College in Waco. He

has an MA in English from Baylor University, and his research interests include

gamification of learning. His hobbies include traveling, reading, writing, and

games of all sorts.