|

Writing center tutoring consists of a variety of speech acts

involving one’s knowledge and understanding of different norms and

traditions of communication popular in that culture in which a concrete

instance of interaction takes place (Fujioka, 2012). One such pragmatic

aspect implying the existence of different social norms and cultural

values is associated with compliments and responses to compliments. As

shown in previous research (e. g., Bardovi-Harlig, 1999, 2001; Kuriscak,

2010), not all speakers in their native language (L1) respond to

compliments and other speech acts in the same way. Second language (L2)

learners also show much variation in how they perceive and carry out

their own or react to others’ compliments and other kinds of speech

acts. That is why in the course of my work as a writing center tutor, I

became interested in investigating various factors (e.g., location of

the interaction, age and social status of the interlocutor, the level of

familiarity with the interlocutor and the culture of the interlocutor’s

home country, various personality measures, study abroad experience,

motivation, and proficiency level in the L2) which should probably have

some influence on L2 speakers’ production of their own and reaction to

others’ speech acts, including their responses to others’ compliments. I

also realized that use and interpretation of compliments and compliment

responses by writing center tutors and student writers in appropriate

ways is one way to ensure effective communication between tutors and

students in consultations. This study examines how native-speaking (NS)

and nonnative-speaking (NNS) student writers use compliment responses

with NS and NNS writing center tutors.

The corpus consisted of 17 transcripts of face-to-face

consultations between tutors and students, both groups including NS and

NNS individuals, at a writing center of a U.S. university in the

south-central part of the country. All those consultations were

videotaped in 2014 for conducting the study into the intonation units

observed in the tutor and client speech. Each consultation lasted 45–65

minutes (mostly 50–55 minutes). Twenty-seven subjects (10 tutors and 17

students) were involved in this study, including six NS and four NNS

tutors (both male and female), and nine NS and eight NNS students (both

male and female). All sessions analyzed in this study were divided into

four groups: 1) the sessions conducted by NS tutors for NS students, 2)

the sessions by NS tutors for NNS students, 3) the sessions by NNS

tutors for NS students, and 4) the sessions by NNS tutors for NNS

students.

In the process of research, a transcription of writing center

consultations retaining the phonological images of words and

sociolinguistically relevant information was used. All features of

natural speech (including word repetitions, use of interjections and

pause-fillers, occurrences of stumbling, etc.) were reflected in the

transcription and preserved in the examples cited in this article. The

occurrences of compliments and compliment responses used at those

sessions were identified and categorized into groups and subgroups

following Ishihara’s (2010) classification of different kinds of

compliment responses. According to Ishihara, common responses to

compliments can be categorized into acceptance, mitigation/deflection,

and rejection. Each of these categories includes several subcategories,

as follows:

- Acceptance

-

Token of appreciation (Thanks/Thank you)

-

Agreement by means of a comment (Yeah, it’s my favorite, too)

-

Upgrading the compliment by self-praise (Yeah, I can play other sports well too)

- Mitigation/Deflection

-

Comment about history (I bought it for the trip to Arizona)

-

Shifting the credit (My brother gave it to me/It really knitted itself)

-

Questioning or requesting reassurance (Do you really like them?)

-

Reciprocating (So’s yours)

-

Downgrading (It’s really quite old)

- Rejection

-

No Response

-

Request Interpretation

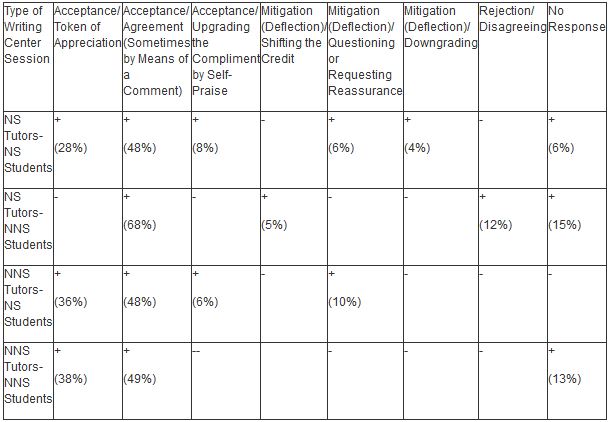

This study reveals that the use of compliment responses in the

writing center sessions is characterized by some common and varying

features. Information about the presence (“+”) or absence (“–”) of

certain strategies and substrategies in the compliment responses, which

were revealed in certain groups of the writing center consultations, is

summarized in Table 1. It also indicates the token frequency of using

various forms of compliment responses in all four groups of the sessions

investigated in this study.

Table 1. Variety and Token Frequency of Using Different Kinds

of Compliment Responses in Writing Center Practice (Click to enlarge)

Note. Percentage

indicated in this table reflects the results of calculating the token

frequency of using different kinds of compliment responses identified in

the corpus of the study. It means that the percentage data used in our

analysis refer to the overall frequency of using compliment responses in

the transcripts of the study, including the instances of the responses

having the same structure and containing the same lexical units. The

token frequency of the compliment responses which were identified in the

corpus of the study was calculated for enhancing some qualitative data

obtained within the present analysis. Based on all these data, it was

possible to find various similarities and differences in the ways of

using compliment responses at the writing center sessions conducted by

NS and NNS tutors for NS and NNS students.

The results suggest that the smallest range of different kinds

of compliment responses was observed in the transcripts of the sessions

conducted by NS and NNS tutors for NNS students. A more limited number

of the strategies and substrategies used in NNS students’ compliment

responses compared to those of NS students can be connected with the

fact that, unlike the NS students of the university where this study was

conducted, the NNS students have lived in another country for the

majority of their lives. Therefore, they may not be familiar with the

local traditions of communication and particularly with the pragmatic

compliment-related norms preferred in the American culture. As English

is the L2 for NNS students and NNS tutors, some limitations in the use

of certain forms of compliment responses can also be connected with NNS

students’ L2 proficiency, as well as with the actual level of their

familiarity with the local traditions of communication.

As can be seen from Table 1, the Acceptance strategy of

providing compliment responses (by means of agreement and/or token of

appreciation) prevailed in the transcripts of all 17 sessions analyzed

in this study. According to the results, in many cases, the NS students

resorted to the use of the Acceptance strategy as well (see Table 1).

Since both NS and NNS students used the Acceptance strategy in most of

their compliment responses, it is possible to assume that that the

pragmatic choice of a compliment response may depend on other factors,

including social distance, imposition, and social power. For example, in

the following fragment of an NS tutor-NS students’ writing center

session, the student combines expressing his/her agreement with the

tutor’s words with a comment explaining his/her choice complimented by

the tutor:

Tutor (T): By the way, it’s hilarious how you’ve renamed these things.

Student (S): Ya, ya, if I like keep the same

one, then it replaces the file. I’m like no I don’t want to

replace.

T: Ya, ya, please, no, ya. OK. So let’s read the next part, then.

In this fragment, the student agrees with the tutor’s words

(“Ya, ya”). This way he/she shows his/her solidarity with the tutor’s

opinion. At the same time, he/she explains why he/she wouldn’t like to

rename the files with the examples of his/her writing anymore.

Interestingly, in the next part of this dialogue, before the tutor and

the student continue their discussion, the tutor confirms the student’s

wish not to rename his files once again (“Ya, ya, please, no, ya”).

However, his second remark does not contradict the compliment expressed

in his/her previous remark (“it’s hilarious how you’ve renamed these

things”), as in this case he/she just wants to say that, although the

student renamed his files effectively last time, it is not worth trying

to rename them once again.

Another strategy that was often observed in almost all of the

writing center sessions (except the NNS tutors-NS students’ sessions)

was the No response strategy, for example:

T: Yeah. Actually, that’s wonderful. Excellent! You have great instincts.

S: [Nodding head to show agreement with the tutor’s words.]

T: Fantastic!

In this fragment of an NS tutor-NNS student’s session, the

student does not verbally respond to the tutor’s compliment. He/she just

nods her head to show that he/she agrees with the tutor’s compliment

about some of her personality traits reflected in her writing. A

relatively frequent use of the No Response strategy probably results

because, in some cases, tutors’ compliments were followed by their

additional explanations, comments, and suggestions. Therefore, in such

cases students were more likely to react to those additional

explanations and comments but not to the compliments in the initial

parts of tutors’ remarks. It is also logical to assume that such factors

as the actual level of students’ English language proficiency, their

previous communication experiences with American English native

speakers, their individual psychological peculiarities and personality

traits, and the degree of their familiarity with the pragmatic norms

popular in the American culture should also influence their use of the

No Response strategy. Finally, NS and NNS tutors’ and students’

expectations about their actual knowledge of the necessary pragmatic

norms and about their previous experience of communication in some

similar situations could play some role in students’ choice of the No

Response strategy as well.

It also follows from the results of this study that some kinds

of compliment responses were used only at one or several sessions. In

particular, only the NNS students working with NS tutors resorted to the

Rejection (disagreeing) strategy and to the Mitigation/Deflection

strategy by means of shifting the credit:

T: Great. Oh, yes, yes, – that’s fantastic too.

S: Well, that was actually one of them who said that.

In this case, when the tutor compliments an idea reflected in

the student’s writing, the student does not accept or reject the tutor’s

compliment but shifts the credit to another person who, from the

student’s point of view, was the first person who suggested that idea

and who thus, in his opinion, deserves this compliment more than

he/she.

It is also important to mention here that, unlike the three

other kinds of sessions, no use of the No Response strategy was observed

at the NS tutor-NNS students’ sessions. At the same time, only NS

students working with NS and NNS tutors resorted to upgrading the

compliment by self-praise or to questioning or requesting

reassurance:

T: Uh-huh. Uh-huh. I think it’s pretty good. En. Er. It expands and reviews the most important things…

S: OK. So reviews?

T: Yeah.

In this case, the NS student is complimented by the NNS tutor

on the content and the ways of developing his/her ideas in the paper

discussed during that writing center session. However, the use of the

question “So reviews?” in the student’s response indicates his/her

doubts about one of the aspects mentioned in the tutor’s compliment. So

in his/her response to this compliment, the student wants reassurance

that the tutor’s words are true and that the quality of his/her paper is

good.

As was shown earlier, all aforementioned peculiarities observed

only in one or two certain groups of the writing center consultations

investigated in this study can probably be connected with the influence

of students’ L1 and their home country culture as well as with the level

of NNS students’ L2 proficiency. The degree of their familiarity with

the local traditions of communication in different social situations

might have influenced their pragmatic choices as well. Finally, some

psychological and social factors, including social distance, social

power, and imposition—as well as the differences in understanding of the

principle of modesty peculiar to different cultures—might have had much

impact on choosing or not choosing certain strategies of providing

compliment responses. According to Wolfson (1983), lack of pragmatic

competence can easily lead to a negative interpretation of the

interlocutor’s personal traits and stereotypes of other cultures. It is

logical to conclude that the aforementioned factors need to be

considered in the system of training writing center tutors so that they

can use and react to different forms of these and other speech acts in

appropriate and effective ways.

In addition, the findings obtained in this study may also have

some importance in terms of planning the content and purposes of

EFL/ESL, business English, introduction into speech, and other classes

for university students connected with the questions of language use and

communication. Because compliments and compliment responses reflect

positive values underlying different cultures, instruction regarding the

use of these speech acts can enhance students’ cultural literacy as

well as their linguistic control of these speech acts. Besides,

compliments and compliment responses can also serve as a conversational

tool to help writing center tutors and clients as well as L2 learners to

establish solidarity in the process of communication with NS and NNS

speakers of a certain language (Ishihara, 2010). Through proper training

or instruction, writing center tutors and L2 learners can become better

prepared to provide and interpret others’ compliments and compliment

responses. Ultimately, such preparation should contribute to the

enhancement of intercultural communication and cross-cultural

understanding in today’s globalizing world.

References

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (1999). Exploring the interlanguage of

interlanguage pragmatics: A research agenda for acquisitional

pragmatics. Language Learning, 49, 677–713.

doi:10.1111/0023-8333.00105

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2001). Evaluating the empirical evidence:

Grounds for instruction in pragmatics? InK. K. Rose & G. Kasper

(Eds.), Pragmatics in language teaching (pp. 13–32).

Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Fujioka, M. (2012). Pragmatics in writing center tutoring:

Theory and suggestions for tutoring practice. Kinki University

Center for Liberal Arts and Foreign Language Education

Journal, 3, 129–146.

Ishihara, N. (2010). Compliments and responses to compliments.

Learning communication in context. In A. Martinez-Flor & E.

Usó-Juan (Eds.), Speech act performance. Theoretical, empirical

and methodological issues (pp. 179–198). Amsterdam, The

Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Kuriscak, L. M. (2010). The effect of individual-level

variables on speech act performance. In A. Martinez-Flor & E.

Usó-Juan (Eds.), Speech act performance. Theoretical, empirical

and methodological issues (pp. 23–39). Amsterdam, The

Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Wolfson, N. (1983). An empirically-based analysis of

complimenting in American English. In N. Wolfson & E. Judd

(Eds.), Sociolinguistics and language acquisition

(pp. 82–95). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Olga Muranova is

currently a fourth-year Ph D student majoring in TESOL/linguistics and a

graduate teaching/research assistant in the English Department at

Oklahoma State University. Her research interests include text

linguistics (especially the language of popular science texts),

discourse and genre analysis, stylistics, intercultural bilingualism,

English for specific purposes teaching, and teaching ESL/EFL

writing. |