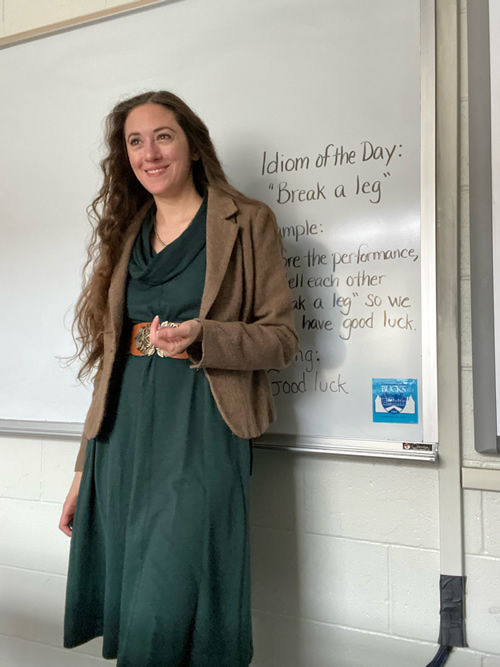

Meet Meg Eubank: 2022 TESOL Teacher of the Year

Interview by Fares J. Karam

The 2022 TESOL Teacher of the Year, Meg Eubank, is

currently a professor at Bucks County Community College in Pennsylvania and a

doctoral student at the University of Houston. Meg has worked with thousands of

diverse people from all over the globe in roles as a college instructor,

nonprofit director, professional tutor, high school teacher, and curriculum

designer.

The 2022 TESOL Teacher of the Year, Meg Eubank, is

currently a professor at Bucks County Community College in Pennsylvania and a

doctoral student at the University of Houston. Meg has worked with thousands of

diverse people from all over the globe in roles as a college instructor,

nonprofit director, professional tutor, high school teacher, and curriculum

designer.

Fares J. Karam, assistant professor of TESOL at the

University of Nevada, Reno, has asked Meg some questions to help us get to know

her.

Congratulations on this award and

important achievement! What does being selected as TESOL Teacher of the Year

mean to you on a professional and personal level?

I am greatly honored and humbled, because there are

many hard working and deserving teachers doing great work during this difficult

pandemic. This recognition is exciting and validating and it inspires me to

keep working to improve my teaching and help others learn the best methods to

work with English language learners. I have to acknowledge, too, the excellent

education I received at my alma mater, Arcadia University, which is where I

learned many skills that I’m being awarded for today, and where my love of

teaching was cemented.

Tell us a bit about how and why you

chose to become a TESOL professional.

My journey to becoming a TESOL professional was an

evolution. I began as an elementary education major and English minor from

Arcadia University who graduated into a hiring freeze during a recession. I was

hired part time in the Tutoring Center at Bucks County Community College as an

ESL (English as a second language) specialist because I was good at explaining

complex ideas simply and teaching English grammar and vocabulary. I had worked

with younger English language learners during student teaching, but really fell

in love with ESL by working with the diverse group of students at the community

college.

In 2011, a coworker told me that a local nonprofit

was looking for people to help teach community English classes to immigrants. I

started working there, and returned to Arcadia University to become certified

in ESL because working with people from all over the globe was incredibly

rewarding and felt like my calling. A decade later, my roles in the nonprofit

had encompassed volunteer, board member, program coordinator, and eventually

executive director when the retiring founder asked me to take over. By 2020, I

had been able to help several thousand students from over 100 countries.

During these years, I continued at the community

college teaching as an adjunct. When the pandemic started, I taught ESL to

international students at a private school, and this year I was brought on as

full-time faculty at Bucks County Community College, where I continue to work

with students from a wide variety of backgrounds.

How did you support your multilingual

students during the pandemic, and what advice do you have to TESOL

professionals looking for ways to support their students via remote learning?

My teaching centers around creating a community of

learners. It is important to me to choose a diverse curriculum that reflects

people from all backgrounds, races, and cultures that is both representative of

my students but also introduces new ideas, as well as vary activities and ways

of presenting information. My biggest challenge during the pandemic was that

many of my students at the private school had returned to their native

countries and were in different time zones! The most difficult task was getting

sleepy teens halfway across the globe to attend class. Virtual learning changed

some of the usual ways we teach.

Meg teaches a Zoom class.

However, whether hybrid, synchronous, or

asynchronous instruction, technology can be an advantage. Some techniques

include breakout rooms on Zoom with small groups, one-on-one conferences, whole

group activities, plus unique experiences like making and sharing videos,

creating a virtual community using social media and digital portfolio tools,

sharing audio clips to converse across time zones, using the chat box in Zoom

to do “waterfalls” of shared ideas, private chatting for students who are not

comfortable asking a question aloud, and ultimately making an inclusive

community with a wide variety of ways to engage. Make sure to present

information verbally, visually, written, recorded, and in as many ways as

possible for students, and implement UDL (universal design for learning)

strategies.

It is also imperative to make sure every student

has equitable access to the tools they need. This year, it was even more

important to use technology and sites students could access, that there was

great flexibility in how students could complete and hand in work, and to offer

alternative ways to do assignments with lots of differentiation. Keep lines of

communication open. I checked in daily with each individual as we learned

authentic and relevant lessons and engaged in a lot of culture sharing to build

a strong community of learners.

Can you please share some of your

experiences working and leading nonprofit organizations that support

multilingual learners?

Can you please share some of your

experiences working and leading nonprofit organizations that support

multilingual learners?

My work with local nonprofits has centered on a

vision of global family members working together to advocate for themselves and

connect with one another, building community and support. One big challenge is

how to communicate with non-English speakers to inform them of services.

Word-of-mouth does not reach enough people, so it is important to build

partnerships and community. The nonprofit I ran expanded across three counties,

from 150 registrations to 400 a term, serving over 1,000 students every year

and resulting in a 146% increase in enrollment since I began because we built a

strong network in the communities where immigrants were living and working. As

a result, there was incredible support among the immigrants, and we created a

family of people from different countries who offered each other rides to class

and helped one another. If a mother needed to bring her child to class, we

welcomed them. I connected with over 75 community organizations and nonprofits

to hold classes, partner in workshops and services, and connect students to

resources. Beyond academic classes, I initiated working closely with advocacy

groups to make changes at the local, state, and national level, and to empower

people to advocate for themselves.

The best rewards were the goals that my students

reached—a Liberian grandmother who learned to read and write for the first

time; a Mexican victim of human trafficking and sexual abuse that earned her

GED, found a job, and passed her driver’s test; an Eritrean widow with a

toddler son who learned to communicate and navigate her new community; and even

the Chinese seventh grader who suffered from isolation on top of her natural

shyness during the pandemic, but grew into a chatty, creative, productive

student by the end of the school year.

What advice do you have to novice

TESOL colleagues? More specifically, how can they continue to support and

advocate for multilingual learners both inside and outside the

classroom?

The biggest key that opens the door to

compassionate teaching is: Remember that your students are people with complex

feelings and individual goals. I remember a grandmother from China came to

class feeling lonely and isolated, not being able to speak to others in her

community. She studied diligently, and one day walked into class with a big

smile on her face, glowing with happiness. She revealed that she made a new

friend, her neighbor, and had a full conversation in English about their

gardens. She had been craving social interaction with someone her age but

needed to have working proficiency in the same language in order to find that

connection in America. Humans need relationships, and we can help students gain

the tools to connect with others.

Teaching English language learners, we encounter

students from all over the world. As they learn from us, we also learn from

them. Our world becomes larger being exposed to so many different individuals

from all over the globe, but also becomes smaller as we realize that we all

have so much in common. Everyone is concerned with the same worries, like caring

for their families and trying to plan for the future. Our humanity links us in

many ways, and this is essential to remember. The driving forces that everyone

encounters as humans are the same, and ultimately we are all concerned about

our loved ones and trying to do the best we can.

Fares J.

Karam is an assistant professor of TESOL at

the University of Nevada, Reno. His scholarship focuses on the language and

literacy development of multilingual learners from immigrant and refugee

backgrounds. His research has been published in Applied

Linguistics, Research in the Teaching of

English, and TESOL Quarterly—among

others.