Adult Learners in SLW (Part 1): Content-Based Instruction

by Rebeca Fernández

In the digital age, writing has become a routine

aspect of social, educational, and workplace communications. Consider a call

center worker or the attendant at a car repair shop, whose job can entail

reporting on conversations with customers or describing repair work,

respectively, into a computer database. For the individual pursuing a job

requiring a 4-year degree, the rhetorical demands and amount of writing are

even greater (Droz & Jacobs, 2019). Yet, for several years, the

National Association of Colleges and Employers’ (2021) Job Outlook

2022 survey of employers has pointed to the gap between employers’

expectations and the proficiency in communication skills, including writing, of

recent college graduates.

Writing is

especially important to immigrant and refugee students, who require it, along

with other English literacy skills, to pursue further education and achieve

economic self-sufficiency in their new country. In the adult English as a

second language (ESL)/English for speakers of other languages (ESOL) programs

that serve them, a focus on writing can support multiple language skills and

modes (Fernandez, 2019) while also facilitating content learning (Manchón,

2011).

Content-Based Instruction in Adult Education

Content-based instruction (CBI) is a

pedagogical approach to second language teaching characterized by the following

(Brinton et al., 2003):

-

Language is learned as part of

a content area course, unit, or lesson.

-

The sequence and form of

language learning are dictated by the content.

-

The content is determined

by the academic needs and interests of the learners.

-

Learning builds on

learners’ knowledge, language, and previous learning experiences.

Many non-credit-bearing

adult education program courses rely on some variation of CBI. Although CBI

courses often focus on unpacking class readings or lecture material, such

courses are also rife with robust opportunities for writing (Brinton &

Griner, 2019) that teachers may overlook without quality professional

development on the teaching of writing (Fernández et al. 2017).

The

following will provide adult ESL instructors with a step-by-step guide for

designing theme-based courses for CBI that expand opportunities for students to

write for different audiences and purposes, while improving their vocabulary,

grammar, speaking, listening, and reading skills. It features an example of a

theme-based CBI course I taught in collaboration with a local history museum

and funded through the English Literacy and Civics (EL/Civics) grant program.

The

following will provide adult ESL instructors with a step-by-step guide for

designing theme-based courses for CBI that expand opportunities for students to

write for different audiences and purposes, while improving their vocabulary,

grammar, speaking, listening, and reading skills. It features an example of a

theme-based CBI course I taught in collaboration with a local history museum

and funded through the English Literacy and Civics (EL/Civics) grant program.

A Quick Guide to Designing a

Writing-Centered Content-Based Instruction Course

Before

delving into design, instructors should know that CBI course development is

often iterative and not set in stone. A general roadmap for teaching and

learning is helpful in the beginning, but components of the course, especially

writing tasks and assignments, may have to be modified or added to address

student needs and interests as they arise. The following questions, though not

necessarily in this order, can help in the early planning stage (adapted from

Brinton et al., 2003):

-

What are the goals for and

expected outcomes of this specific program or course?

-

What approach/model/format

will you use?

-

Who are the learners, and

what are their needs and interests, now and in the future?

-

What authentic materials

can you find and use?

-

What instructional

strategies will you use?

-

How will you know that

course goals are being achieved?

1. Set Student-Centered

Goals, Whenever Possible

Course

topics and goals in U.S. federally funded adult ESL programs are often created

in response to local workforce development needs, assessment targets, and

funding requirements. Although these constraints limit the setting of

student-centered goals in the early stages of planning, adding general writing

goals under communication skills may help set the tone for writing among

students.

➣Real-Life Example

The goals of

the CBI course featured in this article, known colloquially as the “museum

course,” were initially established by my supervisor, the Adult ESL Program

director, who was inspired by Columbia Teachers’ College Museum Education

courses. In her grant application, she persuasively argued for the alignment of

EL/Civics objectives and the knowledge of local history, community integration,

and increased parental involvement that students could achieve by partnering

with the Levine Museum of the New South, a local history museum and field trip

destination for the area’s public school students. This rationale became the

basis for the initial course goals. In addition, because students had to demonstrate

progress on the CASAS reading test, the writing goals could be justified from

the beginning.

2. Create a Tentative

Framework in Advance

A CBI

syllabus may be approached in several ways, depending on whether the course is

adjoined or stand-alone. If paired with a credit-bearing content course, the

CBI course may follow that course’s syllabus structure and weekly assignments

to help students meet that course’s objectives. An autonomous, theme-based CBI

course may afford instructors greater flexibility. Syllabi may be organized

around essential questions or topics centered on a common theme and/or a

chronology of events. Language skills and content knowledge can then be shaped

by the materials available, as discussed in the next section.

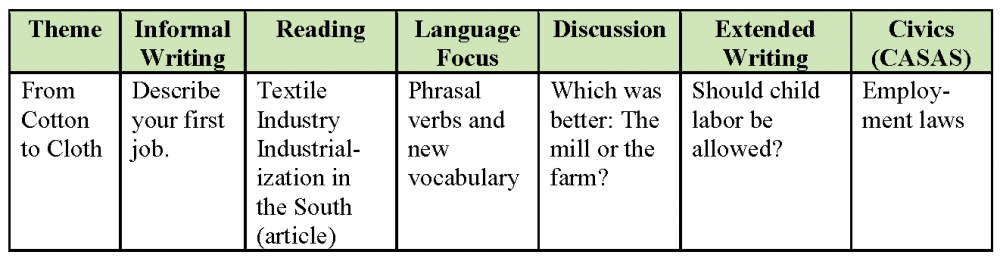

➣Real-Life Example

I designed the museum course around the Levine Museum of the New South’s permanent exhibit, which documents the history of the region since the Civil War through

a series of dioramas, each the title of a unit theme. To enhance opportunities

to write, each unit included

- a

warm-up writing activity (sometimes done collaboratively or used in a

think-pair-share activity afterwards),

-

an

authentic reading sample,

-

focus-on-form work,

-

discussion topics,

-

an

extended writing prompt, and

-

practice CASAS test

questions (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Syllabus Framework and Unit From the Museum Course

Click here to enlarge.

3. Take Advantage of

Digital Tools to Select and Modify Authentic Materials

Authentic

materials allow adult ESL students, who are often isolated by language and

other social barriers, to interact with real-world discourses in meaningful

ways (Roberts & Cooke, 2009). In the writing-enhanced CBI classroom,

authentic materials accessed on the internet can become the basis for rich

conversations and a springboard to writing, provided they are scaffolded

sufficiently for students. With the help of digital tools, hyperlinking,

glossing, translating, or adding images can make materials more accessible and

support the learning of unfamiliar words.

Authentic

texts (e.g., readings, films, podcasts) do not have to be used in their

entirety. A podcast clip can be turned into a meaningful dictation activity,

used to generate discussion and, for more advanced students, as the basis for

extended writing. Students at all levels can also practice writing skills by

captioning videos, memes, or other visual material.

➣Real-Life

Example

In the

museum course, images and excerpts of archival documents worked well as

authentic materials. Students at all levels could describe historical

photographs, however simply, and empathize in writing with the humble lives of

sharecroppers laboring to support their families under harsh conditions.

4. Design Writing Tasks

According to Students’ Learning Needs and Interests

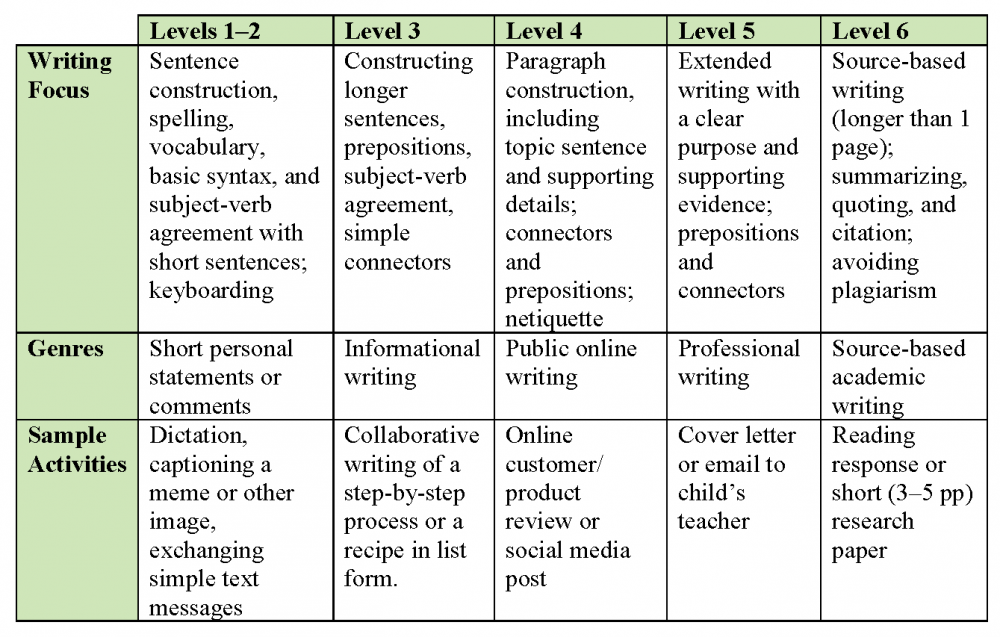

Although

there are six educational functioning levels in adult ESL (National Reporting

System, 2019), most classes are multilevel, even when students enrolled perform

similarly on the placement test. Assessing students informally by asking them

to complete a personal writing task at the start of the course can assist you

in setting individual writing goals for students and planning appropriate

writing tasks and activities. Table 2, compiled from data in a national survey

of adult ESL teachers (Fernández et al., 2017), may also provide a useful

comparison.

Table 2.

Writing Focus of Adult ESL Instructors by Educational Functioning Level With

Related Genres and Sample Activities (Adapted from Fernández et al.,

2017)

Click here to enlarge.

➣Real-Life

Example

Designed for Levels 3 and 4, the museum course’s

writing tasks tended to produce student texts from a few sentences to

two-thirds of a page in length. I used readings, graphic organizers, and

sentence templates to support students at different levels with the tasks.

Assignments were also modified and enriched as students shared their rich funds

of knowledge. For instance, during a discussion about a reading passage about

traditional cotton farming, a group of students who had woven cotton thread

from a young age described the cotton-to-cloth process to the class, prompting

me to modify the writing assignment so that students could apply new vocabulary

(e.g., bud, blossom, boll), demonstrate their content expertise, and expand

their language skills.

5. Assess Student

Progress and Course Goals Through Writing

Writing can

allow you to gauge and document student progress toward their personal and

course goals in ways that are more individualized than standardized listening

or reading tests and avoid the time-induced anxiety of speaking tests. For CBI

writing tasks to align to course goals, you will need to elicit more than

personal writing throughout the course.

As with the

sample unit in Table 1, you may ask students for personal writing as a lesson

warm-up or to make sense of new information. A quick glance at students’

informal writing at the start of a unit or student comments in a collaborative

annotation platform, such as NowComment,

can act as a formative guide for subsequent reading and language instruction.

As the class progresses into the unit theme, asking students to refer to

readings or discussions in extended writing can help you determine whether

progress toward content and language objectives is being made.

To support

learning, these longer drafts will require more attention. Ferris (2019) lists

best practices for responding to student work, among them, meeting individually

with students to focus on priority areas, such as content and organization.

With respect to language, identifying unclear passages may be the most

efficient approach in the first draft (Campbell et al., 2020). During 2- to

3-hour adult ESL classes, you may use class time to read drafts and hold

writing conferences, ideally in a computer lab; because not all students

compose or keyboard at the same rate, you’ll have time to work on meetings with

all students.

Conclusion

Writing-enhanced CBI tacitly

acknowledges that students benefit from participating in multiple forms of

writing. From consolidating word knowledge by handwriting notes from the board,

to practicing listening comprehension through dictation exercises, to

developing rhetorical knowledge by writing paragraphs and essays, writing can

be as much an act of the mind as it is of communication. It can support deep

learning of content and language as well as create a space for students to

gather their thoughts, find community, and advance in their employment or

educational goals.

The next two

parts of this series on adult learners in second language writing explore other

ways that adult ESL/ESOL instructors can incorporate more writing into their

courses. In Part 2, Joy Kreeft Peyton offers strategies for stimulating and

scaffolding student writing at multiple levels. Part 3 by Kirsten Schaetzel

addresses concerns about writing and assessment by guiding instructors on the

use of test prompts to teach academic writing.

References

Brinton, D.,& Griner, B. (2019). Building pathways for writing development in the content areas. In K. Schaetzel, J. K. Peyton, & R. Fernandez (Eds.), Preparing adult English learners to write for college and the workplace (pp. 66–89). University of Michigan Press.

Brinton, D.

M., Snow, M. A., & Wesche, M. (2003). Content-based language

instruction. University of Michigan Press.

Campbell,

S., Fernandez, R., & Koo, K. (2020). Artifacts and their agents. In A.

Frost, S. B. Malley, & J. Kiernan (Eds.), Translingual

dispositions (pp. 33-62). WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/translingual/chapter2.pdf

Droz, P. W.,

& Jacobs, L. S. (2019). Genre chameleon: Email, professional writing

curriculum, and workplace writing expectations. Technical

Communication, 66(1), 68–92.

Fernández,

R. (2019). Writing as a basis for reading, and so much more. In K. Schaetzel, J. K. Peyton, & R.

Fernandez (Eds.), Preparing adult English learners to write

for college and the workplace (pp. 23–51). University of Michigan

Press.

Fernandez,

R., Peyton, J. K., & Schaetzel, K. (2017, August). A survey of writing

instruction in adult ESL programs: Are teaching practices meeting adult learner

needs? Journal of Research and Practice for Adult Literacy, Secondary,

and Basic Education, 6(2), 5–20. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/55a158b4e4b0796a90f7c371/t/

59782f28e58c62b0e4b701cc/1501048703128/Summer+Journal+

Interactive+FINAL.pdf

Ferris, D.

(2019). Providing feedback on students’ writing. In K. Schaetzel, J. K. Peyton,

& R. Fernandez (Eds.), Preparing adult English learners to

write for college and the workplace (pp. 141–161). University of

Michigan Press.

Manchón, R.

M. (Ed.). (2011). Learning-to-write and writing-to-learn in an

additional language. John Benjamins.

National

Association of Colleges and Employers. (2021, April). Career

readiness: Competencies for a career-ready workforce. https://www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/competencies/career-readiness-defined/

National

Reporting System for Adult Education. (2019, August). Test benchmarks

for educational functioning levels. https://nrsweb.org/resources/test-benchmarks-nrs-educational-functioning-levels-efl-updated-august-2019

Peyton, J.

K. (2019). Designing writing assignments: Using interactive writing and graphic

organizers. In K. Schaetzel, J. K. Peyton, & R. Fernandez (Eds.), Preparing adult English learners to write for college and the

workplace (pp. 94–117). University of Michigan Press

Roberts, C.,

& Cooke, M. (2009). Authenticity in the adult ESOL classroom and

beyond. TESOL Quarterly, 43(4),

620–642.

Rebeca Fernández is associate professor of Writing and Educational Studies and Multilingual Writing Coordinator at Davidson College in North Carolina, USA. Previously, she taught adult ESL at Central Piedmont Community College, where she developed the museum course featured here. She received a doctorate in language and literacy at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.