Virtual Exchange: Collaborating to Create

by Margita Vojtkulakova

Online language teaching has challenged English

language educators to be creative and flexible in what many have found to be a

difficult learning environment. Though inferior in many ways, in others, online

learning brought about several benefits. The most evident one is the

flexibility inherent in online communication—communication at any time and from

almost anywhere.

Drawing

upon this benefit, I organized a virtual exchange (VE; see O’Dowd, 2021; Tomaš

et al., 2021) that brought together two groups of students: English as a second

language learners from Michigan and English as a foreign language learners from

Slovakia.

Drawing

upon this benefit, I organized a virtual exchange (VE; see O’Dowd, 2021; Tomaš

et al., 2021) that brought together two groups of students: English as a second

language learners from Michigan and English as a foreign language learners from

Slovakia.

Together,

these two groups of students developed an e-book project that we called “This

Is Us” (click here

to see the book). According to Lewis & O’Dowd (2016), there are three

main types of VEs (also known as online intercultural exchanges):

-

information exchange

tasks

-

comparison and analysis

tasks

-

collaborative tasks

For my e-book project, we

incorporated both information exchange and collaborative tasks that included

writing about ELs’ cultures and countries of origin, writing about their

experience living in different countries, and creating the actual e-book. The

following approaches guided the project:

-

Promoting an asset-based view

of English learners (ELs) as multilingual and multicultural citizens. The

entire project built on an approach through which learners were positioned to

be assets to the created collaborating community.

-

Creating meaningful opportunities to produce multimodal

writing, practice descriptive and informative writing, offer peer feedback, and

improve editing skills.

Steps to Develop a Virtual Exchange E-Book Project

1. Find an

International Collaborator

To initiate

a VE project, you’ll need an international partner. In my case, I reached out

to an English as a foreign language teacher in Slovakia I knew from my college

studies who works with learners of the same age as my students.

Here are

some places where you could find collaborating parties:

-

Visit iEARN.org -

Global Project Collaboration website. To connect with the iEARN community,

click here.

Some ideas for VE can be found on their iEARN Project Space page.

-

Visit different platforms

that provide opportunities for networking. Some of those platforms

are:

Reach out to

someone you think would make a good partner and explain the project, including

your preliminary timeline and your goals for your students, to see if they are

interested and able to work with you.

2. Collaborate to

Develop the Exchange

After

finding a collaborator, it’s helpful to discuss the interests of the

collaborating students, language proficiency, their assets, and the possibility

of synchronous meetings. In addition, I recommend discussing what kind of

platform you would be using for your VE and how often you would update each

other on the project.

It’s also

advantageous to have some concrete ideas for projects that may be engaging and

feasible, and to discuss pros and cons of different approaches with your partner(s).

You can discuss which of the three main types of VEs may be the best fit for

your students and goals, and then brainstorm some potential VE projects.

Once you

have a few solid ideas, you can introduce them to the students and let them

choose, or ideally, a project idea comes from the students after mutual

introductions. The introduction can be done via a short video or a written bio

of the class or of each student (using, e.g., Google Docs, Google Slides, Jamboard,

or Padlet).

3. Create an Invested

Online Community

Regardless

of what type of task you choose, be sure to spend some time initially on

creating a positive and respectful collaborative community. First, our students

got to know each other asynchronously by introducing themselves on Padlet.

Then, we had synchronous meetings—in the beginning all together, and after a

couple of meetings in breakout rooms. After a few meetings, students felt

comfortable working in small international teams on a set of challenges

prepared by the teachers. Challenges should offer space for all the team

members to contribute (see Challenge 1; Appendix A) and have students build on

their assets rather than on their language skills (see Challenge 2; Appendix

B).

4. Guide Students to

Create an E-Book

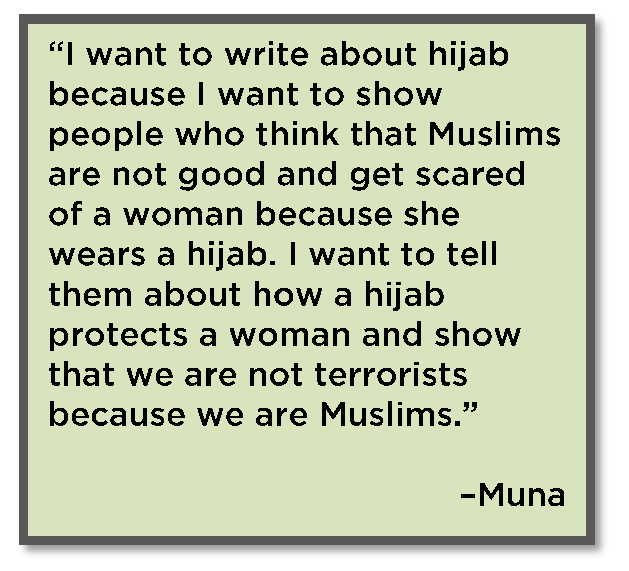

After

brainstorming about what they would like to know about each other, students

dove into informative, descriptive, or personal writing based on the questions

posed from the collaborating party. They were writing about something that they

considered “theirs,” and they had their own background knowledge as an asset to

achieve it. In addition, students had in mind that there was an authentic

audience—someone who was truly interested in their writing.

After

brainstorming about what they would like to know about each other, students

dove into informative, descriptive, or personal writing based on the questions

posed from the collaborating party. They were writing about something that they

considered “theirs,” and they had their own background knowledge as an asset to

achieve it. In addition, students had in mind that there was an authentic

audience—someone who was truly interested in their writing.

Once they

finished the first drafts, students provided feedback to and received feedback

from their international peers. At this stage, learners served as assets to

each other. As language learners from various learning environments, they had

different experiences with English language acquisition. For example, on one

hand, whereas Slovak ELs tend to excel in English grammar and spelling because

these are often viewed as instructional priorities in that context, they often

lack fluency and struggle to use common collocations. On the other hand,

Michigan ELs are exposed to English every day and are generally more fluent,

but many lack experience in structuring paragraphs, using grammar structures

correctly, or spelling accurately.

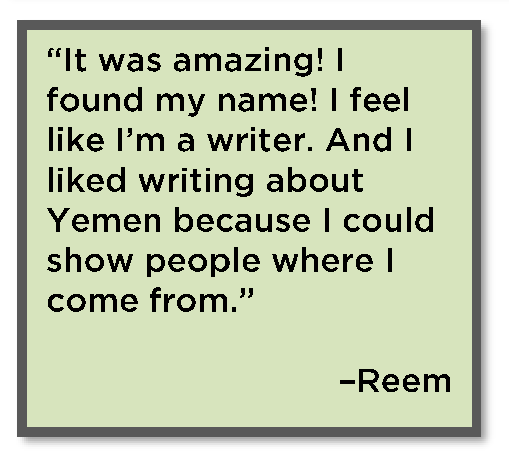

Using

prompts provided in Google Docs, students provided a compliment (“What do you

like about this writing?”) and then a suggestion (“How can the writer make this

writing better?”) to their international peers. After addressing the feedback,

the process of creating an e-book began. This included students making

decisions about pictures, format, and design while developing their creative

and collaborative skills. Instead of pointing out mistakes, the focus was on

giving students a voice and a feeling of authorship. Students enjoyed

practicing these digital skills that contributed to their skillset of global

learners.

Using

prompts provided in Google Docs, students provided a compliment (“What do you

like about this writing?”) and then a suggestion (“How can the writer make this

writing better?”) to their international peers. After addressing the feedback,

the process of creating an e-book began. This included students making

decisions about pictures, format, and design while developing their creative

and collaborative skills. Instead of pointing out mistakes, the focus was on

giving students a voice and a feeling of authorship. Students enjoyed

practicing these digital skills that contributed to their skillset of global

learners.

Online Tools for Creating an

E-Book

For our

e-book, we used Book

Creator, which offers a free account for individual users and

provides a link, which can easily be shared, for collaboration. Following are a

few other resources that can be drawn upon in creating e-books:

-

Google

Slides: A template by SlidesMania can be found here.

If learners do not have regular access to the internet, the slides can be

printed and used as book pages, and then scanned and shared via Google Drive by

the project facilitators. Another option is to exchange hard copies of the book.

-

Canva:

Canva offers numerous templates for posters, newsletters, infographics,

invitations, magazines, and so on.

-

Newlywords:

Newlywords is a resource similar to Book Creator. For free, users can

collaborate on an e-book and can download their final product in a pdf

format.

Concluding Thoughts

Once our

e-book was finished, students took pride in sharing the final product with

their peers, friends, and family. The e-book project was followed up by

reflection and continuous international synchronous meetings.

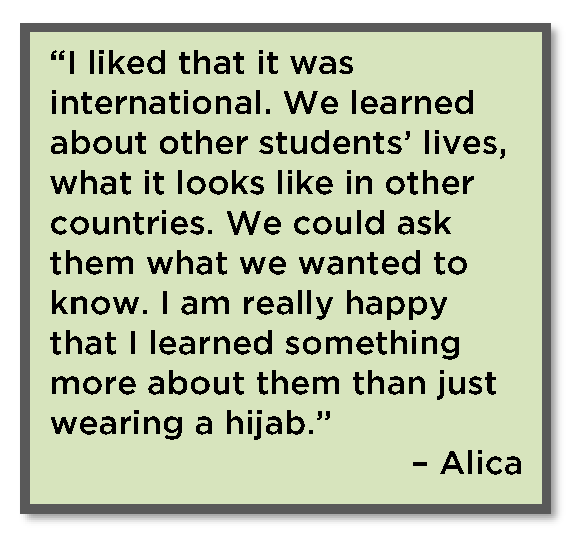

This

international project approached all students through an asset-oriented lens

and capitalized on the advantages of virtual learning. Students were engaged in

interactive tasks, inter- and intra-cultural discussions, and developing a set

of 21st-century skills (global citizenship, creativity, communication). Through

this unique virtual collaborative experience, we increased student engagement

and positive identity while challenging ourselves as teachers to grow into

global educators.

This

international project approached all students through an asset-oriented lens

and capitalized on the advantages of virtual learning. Students were engaged in

interactive tasks, inter- and intra-cultural discussions, and developing a set

of 21st-century skills (global citizenship, creativity, communication). Through

this unique virtual collaborative experience, we increased student engagement

and positive identity while challenging ourselves as teachers to grow into

global educators.

Acknowledgements

I would like

to express my great thanks to the collaborating Slovak educators Ms. Patrícia

Folvarčíková and Ms. Daniela Škurlová from Spojená škola Dominika Tatarku

Poprad. My thanks goes to Dr. Najim Ahmed, my colleague at Frontier

International Academy in Detroit, who helped facilitate the project. I also

want to thank Dr. Zuzana Tomaš for being my mentor in this project and always

inspiring me to do more and better as a teacher.

References

Lewis, T.,

& O’Dowd, R. (2016). Introduction to online intercultural exchange and

this volume. In R. O’Dowd & T. Lewis (Eds.), Online

intercultural exchange: Policy, pedagogy, practice (pp. 3–20).

Routledge.

O’Dowd, R. (2021).

Virtual exchange: Moving forward into the next decade. Computer

Assisted Language Learning. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1902201

Tomaš, Z., Vojtkulakova, M., Lehotska,

N., & Schottin, M. (2021). Examining the value of online intercultural

exchange (OIE) in cultivating agency-focused, (inter)culturally and

linguistically responsive pedagogy: A story of one collaborative international

project for English learners. Language Arts Journal of Michigan,

36(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.9707/2168-149X.2267

Margita Vojtkulakova has TESOL graduate credentials from Matej Bel University in Slovakia and Eastern Michigan University in the United States. She is currently working as an ESL teacher at Frontier International Academy in Detroit, Michigan, USA. She is a published author and a frequent presenter at MITESOL and TESOL conferences.